Introduction

Alexander

Ogston (1766) moved to Aberdeen in about 1785 to start a business at Lochside

dealing in lint and thread, the textiles derived from flax. In 1802 his firm diversified into the

manufacture of candles and progressively became the most important local

producer of this tallow-based means of working and studying in the long

Aberdeen winter nights. Further

innovation followed with the introduction of soap manufacture in 1853 and by

the end of the 19th century Ogstons was one of the two dominant soap

manufacturers in Scotland. In 1899 the

firm merged with its main competitor, the Tennant company of Glasgow. The success of the Ogston manufactory brought

great wealth to the family and the history of this enterprise has been

chronicled elsewhere on this blogsite – “The Remarkable Ogstons of Aberdeen:

Flax, Candles and Soap”.

Francis Ogston

(1803 – 1887) was a younger brother of Alexander Ogston (1799 – 1869), the

second-generation family member to be in charge of the Candle Works on Loch

Street, Aberdeen. Since the elder

brother of Francis had been given the task of managing the family business,

Francis had to look in a different direction for a career. He eventually chose the profession of

medicine, perhaps because his parental home was close to Marischal College, one

of Aberdeen’s two universities prior to 1860 and home to a thriving medical

faculty. This second son of Alexander

Ogston (1766) must have routinely come into contact with both academic staff

and students of the university. His

decision to join the healing profession proved to be fateful, because both

Francis and his two sons, Alexander (1844) and Frank (1846), but especially the

elder, Alexander, achieved great prominence as doctors. Alexander (1844) developed a reputation as

one of the leading surgeons of his generation, especially for his work on

military surgery, but history will perhaps remember him more for his pioneering

research work on the microbial causes of inflammatory illness, often fatal,

that almost inevitably followed surgery up to the late 19th

century. In contrast, Frank (1846) was a

zealous pioneer of public health measures in his adoptive country, New Zealand. The lives of both Alexander and Frank Ogston

are chronicled elsewhere.

But the

Ogstons’ contributions to human health and knowledge were not confined to the

specialities of their three medical members, public health and medical

jurisprudence in the case of both Francis (1803) and Frank (1846) and surgery

in the case of Alexander (1844). In

particular, this latter doctor possessed a towering intellect that was turned

to the analysis of many different issues.

The pursuit of

medicine, while providing a comfortable lifestyle, did not bring the fabulous

material wealth that the nephews of Francis (1803), the cousins of Alexander

(1844) and Frank (1846), derived from the profitable manufacture of soap and

candles. But the counterbalancing gain

for the medical Ogstons was the satisfaction of knowing that they had preserved

the lives and improved the well-being of innumerable patients and members of

the general population. It is a moot

point as to which activity was the more worthy.

Identification

of members of the Ogston family

While the

newspapers published in Aberdeen and the North-East of Scotland form a rich

source of references to the doings of the medical members of the Ogston family,

references to individuals were sometimes expressed in an ambiguous way, though

the context, such as time, place or activity, relating to the particular

instance often helps in resolving which alternative is the correct, or most

probable, identity. “Dr Ogston” could be

a citation to Francis Ogston (1803), Alexander Ogston (1844) or Frank Ogston

(1846), all of whom earned the title on graduation from medical school, Francis

Ogston in 1824, Alexander Ogston in 1862 and Frank Ogston in 1873. All three medical Ogstons also attained the

title of “Professor”, Francis Ogston held the title between 1857 and 1883,

though he could have been referred to by this title until his death in 1887,

due to his Emeritus status. Alexander

Ogston held the Regius Chair of Surgery at Aberdeen University between 1882 and

1909. Frank Ogston although a member of

academic staff at Otago University for many years, only assumed the title of Professor

of Medical Jurisprudence in 1909, although he probably retained that title

until his death in 1917. Even after his

ascent to the august ranks of the professoriate, each of the medical Ogstons

could still be referred to as “Dr Ogston”.

To add to this plethora of possibilities, there was a further,

contemporary, “Dr Alexander Ogston”, another University of Aberdeen graduate,

who practised medicine in the city around the turn of the 19th

century, though he was not closely related to the family under examination in

this study. He had been born in Crathie,

Upper Deeside, in 1868 and graduated from the Aberdeen Medical School about

1894. Subsequently, he lived and

practised in the Rosemount district of Aberdeen until about 1929 and died in

1940.

Francis

Ogston (1803)’s early life and education

Francis Ogston

was born in Aberdeen and baptised on 23rd July 1803 by the Rev Bryce. The establishment where the ceremony took

place is not certainly known, but it may have been St Paul’s Episcopal Chapel

in Loch Street. The location of the

family home at the time is also uncertain, but likely to have been within easy

reach of the candle works at Lochside.

The two witnesses to the baptism of Francis were Alexander Middler and

Francis Mollison, both described as manufacturers, the former having premises

in Gallowgate. Little has been

discovered about the early education of Francis Ogston (1803). He is known to have attended Aberdeen Grammar

School and was admitted to Marischal College to read for a Master of Arts

degree on 30th March 1821, at the age of 17. Francis probably graduated two years later

and then moved to Edinburgh University to study medicine. He took his final medical examinations on 20th

July 1824 and received his diploma in a ceremony on 2 August, aged barely

21. Dr Francis Ogston then travelled

back to Aberdeen for a brief stay before journeying onwards to London by

sea. In the capital he applied for a

passport for entry to France and Holland and on the continent, he visited and

studied at several leading medical centres before returning to his hometown and

establishing himself as a working doctor.

Being from a relatively wealthy family, Francis (or, more likely, his

father) could afford this continental extension of his medical education.

In the 1824 -

1825 edition of the Scottish Post Office Directory for Aberdeen, the content

for which must have been submitted before Francis’ graduation in 1824, “Francis

Ogston MD” is recorded as living at 2 Gallowgate, Aberdeen. The house at this address is known to have

been the family home between at least 1824 and 1832. It appears to have been accessed from

Ogston’s Court, 84 Broad Street.

Gallowgate is a continuation of Broad Street, and the two properties

were adjacent to each other at the junction of the two streets. The designation “MD”, which is usually

employed to denote possession of a postgraduate medical degree, is curious

since Francis only gained his medical diploma from Edinburgh University in the summer

of 1824. Perhaps it stood for “medical

diploma”?

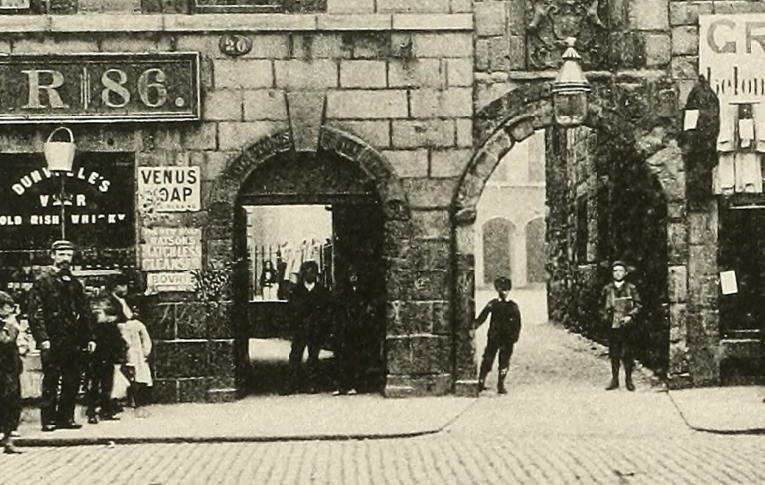

Ogston's Court (left) and entrance to Marischal College (right)

The Aberdeen

New Dispensary

A General

Dispensary, Vaccine and Lying-in Hospital to serve the medical needs of the

sick poor was opened in Aberdeen at 45 Guestrow in 1823. The residential portion of the dispensary

subsequently evolved into the Aberdeen Maternity Hospital. In 1825 the General Dispensary treated 3,914

people who applied for help. That same

year, supported by a list of subscribers, the distinct and separate Aberdeen

New Dispensary began offering succour to the indigent population and treated

1,117 poor citizens. The following year,

1826, there was almost a doubling in the number of patients helped by the New

Dispensary. “The sick receiving benefit

from this charity are now very numerous and the increase (1,146) of the present

year, shows the growing zeal of those to whom its affairs are entrusted. Patients are attended not only through the

city but also in the populous suburbs of Footdee, Dee Village, Hardgate,

Gilcomston, Broadford, etc, while the numbers of those applying for advice from

a still greater distance are considerable.

Medicines have been granted during the year to more than 1,900 sick

poor; while almost the same number have been attended at their own houses. While such is the state of the institution

the managers cannot longer consider it entirely of a private nature and would

therefore call upon the public to join their exertions to those of the

respectable individuals who have hitherto contributed to its support; in order

that means may be afforded for continuing it in its present enlarged state or

for its still further extension”. Another

appeal for donations to assist a third dispensary in Aberdeen, the Footdee

Dispensary, was also made in 1825.

Footdee, “Fittie” to the locals, was the home of the Aberdeen fishing

fleet and associated fish processing works.

Accidents were commonplace in this environment and the medical need of

the residents substantial. It is unclear

if this third dispensary was ever able to initiate services.

Francis Ogston’s first known employment after his graduation from the University of Edinburgh appears to have been as physician to the Aberdeen New Dispensary. He was in post in 1826 but it is not known if he also fulfilled this role in the previous (first) year of its operations. The next annual meeting of subscribers to, and managers of, the Aberdeen New Dispensary was held in December 1827, with Mr William Phillip in the chair. “The subscribers tendered their cordial thanks to the managers for their great care in meeting the purpose of examining into its affairs and inspecting the items of expenditure previous to their annual payment by the Treasurer; to the Treasurer for his steady exertions on behalf of the charity and to the Physician (Francis Ogston) for his arduous and unremitting labours (which are given gratuitously) among the sick poor. The subscribers feel the highest satisfaction in observing the extent of good done at an expense comparatively insignificant and entertain no doubt that the public will continue to appreciate an establishment as strictly charitable as any the city can boast”. So, Francis Ogston was working without remuneration though, on the positive side, he would have been gaining extensive experience of a wide range of ailments and medical conditions, an important benefit for a young doctor. Perhaps his liberal family circumstances could tolerate him working for nothing? Francis Ogston continued in the role of physician to the Aberdeen New Dispensary until 1831.

However, in

1830 alarm bells started to ring for the managers of the New Dispensary, when

demand for services exceeded their financial means to satisfy them. “By rigid economy the funds, which were never

ample have been nevertheless sufficient not only to meet the annual disbursements

but also to leave a small balance; until the present year when demand has

exceeded the usual supply by a few pounds owing to the greater number of poor

requiring medicines during the last year”.

The following year the decision was taken to close down the operations

of the Aberdeen New Dispensary, in the process of which the chairman paid a

generous tribute to their physician.

“The subscribers were however of opinion that as the public did not seem

to appreciate the valuable and gratuitous services of Dr Ogston, nor the great

benefit which thousands have derived from the Institution, that the same be

given up and only a subscription raised forthwith among the managers and others

to discharge the small debt contracted.

The meeting could not take leave of Dr Ogston without expressing their

unqualified approbation of his very meritorious services and their best and

anxious wish for his future success in that profession to which he does

honour”. More than 10,000 poor

Aberdonians had received medical support in the six years of existence of the

New Dispensary.

Francis

Ogston’s early remunerated employment

The first

gainful employment of Francis Ogston appears to have been as police surgeon in

Aberdeen. He was in this post from at

least early 1828 and this is known from a report of the proceedings of the

Circuit Court of Justiciary which opened on 15 April. John Mather, a mariner, was brought up and

accused of having assaulted widow Mitchell or McLean residing in Hutcheon

Street, Aberdeen. A blow felled the old

lady, causing her to bleed profusely. Mather

pleaded not guilty, but the charge was found proven, and he was sentenced to

one year in the Bridewell. Dr Francis

Ogston had examined the auld biddie and reported to the court that her life was

in danger. He would continue with this

role supporting the police for the remarkable period of almost 50 years. “Mr Ogston”, probably Alexander Ogston

(1766), the father of Francis, had been a police commissioner since before 1831

and this fact may have been significant in Francis securing the role of police

surgeon.

Also in 1828,

in November, Francis Ogston mounted a lecture series in chemistry, which was

advertised as follows. “Dr Ogston will

commence his winter course of lectures on chemistry on Mon 3 Nov at 7 o’clock

in the evening in his classroom, Duthie’s Court, Guestrow. The course will be illustrated by many

experiments and apparatus selected by him last summer in Edinburgh. The certificates for attendance on these

lectures are received by the Royal College of Surgeons. Particulars may be learned on applying to Dr

Ogston at No 2 Gallowgate. Aberdeen,

October 7, 1828”. Guestrow, which was

obliterated by the construction of St Nicholas House, itself now demolished,

ran parallel to, and to the west of, Broad Street, the location of Marischal

College and close by Francis Ogston’s family home. This fee-paying course of

chemistry lectures for aspiring doctors was continued at the start of winter in

both 1829 and 1830 but was not detected in subsequent years.

The Aberdeen

Journal’s obituary of Francis Ogston (1803) reported that after his return to

Aberdeen from visiting the continent, he “soon acquired an extensive practice”,

which included private patients.

However, it is unclear how quickly his roll of such clients grew. Presumably, his listing in the Post Office

and other directories as “Francis Ogston MD”, which occurred from1824 – 1825,

was primarily intended to advertise his professional expertise to the upper

classes who could afford to pay for their medical treatment. (At the 1851 Census, Francis Ogston, then

living at 18 Adelphi, was self-described as MD Edinburgh, LTCSE (Licensate

of the College of Surgeons of Edinburgh) and General Practitioner. From 1861 he was listed in city directories

as “Francis Ogston, Physician”). Between

1832 and 1844, Francis Ogston’s place of residence, also the Ogston family

home, changed to Ogston’s Court, 84 Broad Street and he may have had consulting

rooms there. The growing reputation of

Francis Ogston led to him acquiring further roles during the 1830s. In 1832 the Aberdeen Health Board was

constituted, and Francis became a member of this body. This was a time of flowering for mutual

organisations as workers sought to provide for the unpredictable events of

life, such as injury at work or premature death, and for income in retirement. In 1836 the Operative Mutual Assurance

Society was established in Aberdeen by a group of leading citizens, including

Francis Ogston and he was appointed as physician to the Society from its

birth. It rapidly gained in prominence

and was financially successful. In 1844

it held its 8th annual meeting in the Grammar School when, “The

Treasurer stated that during the last seven years they had paid for sick and

funeral expenses upwards of £250, while they had at the same time adding to

their stock upwards of £50 yearly, to provide for after life”. At this time, Francis Ogston was an honorary

director, but it is unclear if he still fulfilled the role of physician to the

society. In 1850 he was a member of the

council of the society. The Aberdeen

Journal was approving of such mutual societies and commented, “In reference to

this Society, we may only state that we believe the benefits derived from it

are 6s per week when sick, £5 payable on death, and £5 per annum of annuity

after 70, all which a man at 25 years can obtain for about 2¼ d per week, and a

man at 40 for about 3¾ d per week. We

should like to see such Societies as the above in every district of our

country”. A further remunerated post was

acquired by Francis Ogston in 1853, when he became the medical officer to the

Aberdeen Board of the United Kingdom Life Assurance Company.

The death of

Alexander Ogston (1766)

Alexander

Ogston (1766), the father of Francis Ogston and the founder of the candle

manufactory, which was the source of the family wealth, died on 27 July 1838 at

Ardoe, the estate he had only recently purchased, on Lower Deeside. Both sons were named as trustees of their

father’s will. Francis appears to have

been detailed to acquire a burial plot at St Clement’s Church, the parish church

of Footdee, which he did for the considerable sum of £30 for his father’s

lair. Several members of the Ogston

family, including both Francis (1803) and his elder son Alexander (1844), two

subjects of this study, were subsequently interred there.

Francis

Ogston’s role as Police Surgeon

The role of

police surgeon was busy, and the pages of the Aberdeen Journal and other local

newspapers frequently contained reports of Francis Ogston’s activities in this

role. An appreciation of the scope of

the job can perhaps best be gained through the following examples, chosen for

their diversity. In June 1831, the

police day patrol found one Moses Dunn apparently drunk in the street. He was taken to the Watch House, the rough

equivalent of a central police station.

It included cells and a room where post-mortem examinations could be

conducted. Moses Dunn quickly became

very ill, and Francis Ogston was called to attend him, but Dunn died. Subsequently, Frances “examined” the body,

possibly conducting a post-mortem dissection, and concluded that he had expired

due to apoplexy (stroke).

A male customer

entered an Aberdeen druggist’s shop in May 1848 to buy 2oz of laudanum (tincture

of opium containing a variety of alkaloids, including morphine and codeine). The druggist became suspicious of the man’s

intentions, as he was rather seedy in appearance. This pharmaceutical retailer then filled a

vial with coloured water, which the man immediately swallowed, left the shop

and went home. On the way he had second

thoughts about his actions, confessed to his wife that he had tried to kill

himself and urged her to send for medical help.

Hysteria then overcame the repentant spouse as he thought he was

dying. Meanwhile Francis Ogston arrived

brandishing his trusty stomach pump and proceeded to evacuate the man’s gastric

contents. He was followed by the

druggist who assured the panicking attendants that the man had only consumed

coloured water and was not about to expire, whereupon the victim resumed his

composure as his impending termination was cancelled.

Seven soldiers

out on the town in August 1850 attacked Constable Gilbert, causing him bruising

on his head and shoulders, cutting his skin, and leaving the marks of strokes

on his cheek, brow and across his back.

Francis Ogston appeared in court to give an account of these

injuries.

In October

1854, Drs Ogston and Jamieson were sent to the scene of the sudden death of a

housekeeper, who had been sleeping with her master after a party, where both

had been drinking. She appeared to have

died from a stab wound to the head with a pair of scissors. Her master, a farmer, was taken into custody

on suspicion of being the perpetrator of her demise. It was then discovered that some years

previously he had spent time in the Aberdeen Lunatic Asylum.

The same year,

a woman in Aberdeen attempted to commit suicide by drinking a large quantity of

laudanum, a remarkably frequent occurrence.

About two hours later Dr Ogston was called to the scene. He used his stomach pump on the victim, but

with little immediate effect. However,

she gradually recovered from her self-inflicted brush with mortality.

In May 1860, a

young man, David Thomson, went out drinking with his mates in Longside, near

Peterhead and then travelled towards Aberdeen on a cart. The inebriated group started arguing and

fighting as they were approaching Ellon, which led to Thomson being put on top

of the cart, possibly unconscious. At

Ellon he was found to have died. The

following day, Francis Ogston was sent to examine the body to determine if the

dead man had been murdered, but he concluded that his death was due to

exposure.

A tragic

maritime accident occurred in 1863 at Aberdeen harbour. Two seamen were sleeping in the forecastle of

a schooner, which was heated by a small stove.

The mate was abed in the after part of the vessel. In the morning he found his two shipmates

insensible. Drs Ogston and Will were

called and managed to revive one man, but the other had died of carbon monoxide

poisoning.

A statistical

analysis has been made of the 133 cases reported in the newspapers involving

Francis and/or Alexander Ogston (1844) in association with their work for the

police. (It appears that Alexander

Ogston never had a formal appointment with the police but probably substituted

for his father in this role, due to serving as assistant to him in his private

practice, probably from 1865). This

sample is unlikely to be close to a random sample of all cases, since some

examples would likely be deemed more newsworthy than others. For example, only 3% of cases reported in the

print media involved assault to or by policemen, yet from Francis Ogston’s

annual reports, (eg. in 1867) a high proportion (39%) involved the police,

usually as victims of assault. Perhaps

injuries reported by policemen were typically of a minor nature? The most fundamental conclusion to be drawn

from this sample is that of cases drawn to the attention of the police, 61%

involved a sudden or unexpected death.

Also, 43% of cases (some of which led to death) involved accidents, and

horses or horse-drawn vehicles were responsible for 21% of these. In some 20% of examples, the involvement of

the law was due to sudden illness, sometimes leading to the demise of the

victim, usually in the street. Almost

15% of cases involved murder, culpable homicide or infanticide and 14% were

examples of suicide or attempted suicide, mostly by laudanum poisoning, though

other methods employed were hanging and throat cutting. Of the sudden or unexpected deaths, post-mortem

examinations were conducted in 17% of cases.

Only one example of firearm use was uncovered and in 6 cases issues of

mental health (real or pretended) were involved.

The role of

police surgeon was not particularly well remunerated, being 20gns per annum in

1846, which deficiency was recognised by the police commissioners at their

meeting of that year when Francis Ogston’s annual report, which was described

as “elaborate and minutely drawn up”, was tabled. The opinion was voiced by a commissioner that

the salary would be justified by the report alone. Perhaps realising that Francis was

under-paid, his emoluments were increased by 50% in the same year. Throughout his career, Francis Ogston never

gave the impression that he was driven by financial gain in his employment

decisions.

Francis

Ogston, additionally, becomes Public Officer of Health for Aberdeen

From late 1865,

a new kind of case started to be dealt with by Francis Ogston and his son

Alexander in their joint role of Public Officer of Health, the inspection and

frequently the condemnation of foods offered for human consumption. The first detected case involved the seizure

of Monte Video beef, pork and hams, which had been seized by Mr George Thomson,

Inspector of Nuisances, from James Allam, grocer and provisions merchant, St

Nicholas Street. These meats were

determined by Profs John Struthers (Anatomy, 1863 – 1889), Francis Ogston, and

Dr Alexander Ogston to be unfit for sale to the public. From 1867 Francis Ogston also conducted large

numbers of pre-employment medicals on police recruits. Other new case types appearing during the

1870s were child neglect, reports of defective drainage and infectious disease

cases onboard visiting ships requiring quarantine measures.

Francis Ogston

becomes an expert in Medical Jurisprudence and marries Amelia Cadenhead

Through his

work as the police surgeon, Francis Ogston must have become familiar both with

the law surrounding police investigations of suspected crimes and unexplained

deaths, and with the procedural formalities of such work. He must also have become closely acquainted

with Aberdeen’s procurator fiscal at the time, Alexander Cadenhead (1786 –

1854). The ancient role of procurator

fiscal was to collect taxes, debts and fines but it evolved during the 18th

century into the court officer responsible for bringing prosecutions and in 19th

century Aberdeen he was the public prosecutor.

The relationship between Alexander Cadenhead and Francis Ogston is

likely to have included interactions between the wider families of the two men

because, in 1841, Francis married Amelia Cadenhead (1819 – 1852), the elder

daughter of Aberdeen’s fiscal. The wedding

took place at Ardoe House, Banchory-Devenick, the grand estate which had been bought

by Francis’ father. At the time of the

marriage, Francis was 38, 16 years older than his bride. A second consequence of his role as police

surgeon was that he became recognised as an expert in the highly specialised

field of medical jurisprudence. This subject was being taught in the

University of Edinburgh from at least 1793, where it was defined as “…treating

of those questions which come before Criminal, Civil and Constitutional Courts

for determination of which the opinion of a Medical Practitioner is required

…”.

Francis Ogston becomes a lecturer in Medical Jurisprudence at

Marischal College

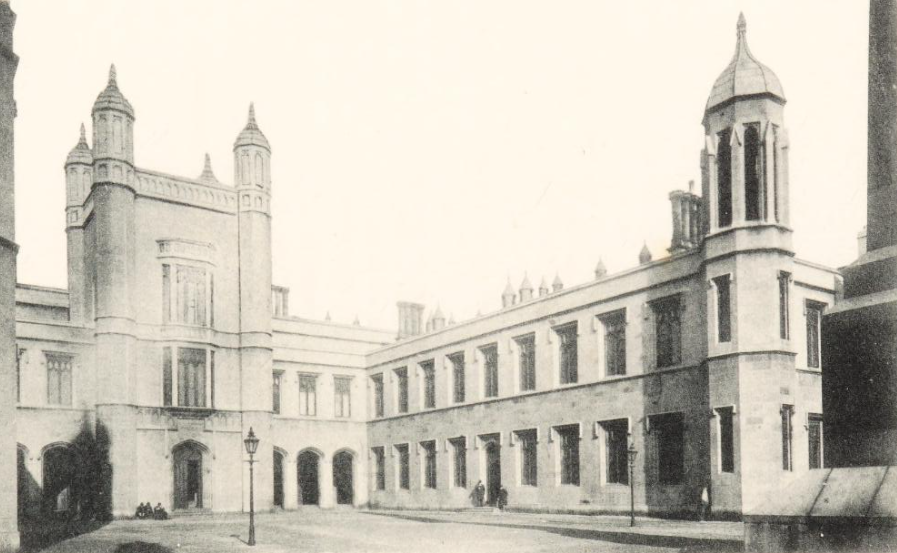

During session 1839 – 1840 in the medical faculty at

Marischal College, where “excellent

accommodation for the Medical Classes will be ready in the new buildings”, Francis Ogston was engaged as a

lecturer on 3 September 1839 and for the first time he delivered a course of

lectures on medical jurisprudence in the University. This lecture series was repeated annually and

in 1844, the fee for attendance was 2gns, which went to the lecturer. In November 1857 the lectureship was

converted, with the sanction of the Crown, to a Chair, supported by an

endowment from Alexander Henderson of Caskieben, and Francis Ogston was

elevated to the new Chair in Medical Logic and Medical Jurisprudence. From that year his lecture course changed its

title to correspond with that of the chair.

In 1860, Aberdeen’s two universities, King’s College in Old Aberdeen and

Marischal College in the New Town merged to form a single “University of

Aberdeen”. As a result, several

professors became redundant and were dismissed but Francis Ogston was retained

in the new institution as professor of medical jurisprudence, though his

lecture course still included “medical logic” in its title. The roles that Francis Ogston played in the

protests which the University Commissioners’ proposals for this academic fusion

engendered, and the development of the Marischal College Medical School are

dealt with elsewhere. Francis Ogston

continued to occupy this chair until July 1883, when he reached the remarkable

age of 80 and resigned. He was replaced

by Professor Matthew Hay. It is not

clear if Francis Ogston continued to lecture in his special subject right to

the end of his tenure, since the last year in which he was advertised as

delivering the course was session 1878 – 1879.

The origin

of the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

Aberdeen’s

original infirmary, located at Woolmanhill near the city centre, admitted its

first patients in 1742. In 1773 it was

designated as the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI) by Royal Charter. The first hospital building was replaced in

1840 with a grand new granite structure designed by architect Archibald

Simpson. Subsequently, the site

underwent further development with the construction of additional hospital

accommodation. In those pre-National

Health Service days, ARI was maintained by charitable donations and overseen by

a board of managers, the members of which were elected annually from amongst

the most generous donors. Francis Ogston

was first elected as a manager of the ARI in 1845.

Francis

Ogston’s children

After his

marriage to Amelia Cadenhead in 1841, four children were born, Jane (1842),

Alexander (1844), Francis (1846) and Helen Milne (1849). Son Francis usually referred to himself as

“Frank”, presumably to create a distinction from his father’s appellation, and

Francis (1846) will be referred to as “Frank” throughout the rest of this

essay. In 1845, Francis Ogston and his

growing brood moved from Ogston’s Court to 21 Adelphi Court adjacent to the

east end of Union Street, the grand main street of Aberdeen city. The reason for the move may well have been

the need for additional accommodation, but perhaps also the requirement for

consulting rooms in a more salubrious part of town. Francis Ogston moved the family home again

three years later, but not far, to 18 Adelphi Court, which remained his domestic

abode until 1866. In 1848, 21 Adelphi

Court was described as being “excellent and commodious … with stable and other outbuildings”. However, Francis’ wife, Amelia, died

prematurely, aged 33, in 1852 and the widowed Francis did not remarry.

Francis

Ogston’s career advances

By 1847, when

he was 44, Professor Francis Ogston’s academic star was clearly rising in the

Marischal College medical firmament. He

had become the convener of the Medical Committee and this role required him to

open the session on 1 November with a general introductory lecture, in the

presence of the Senatus and Medical Faculty academics. The Aberdeen Journal reported that “the

attendance was numerous” and that Francis Ogston’s lecture “was listened to

with the most marked attention”, so much so that Dr Pirrie proposed, seconded

by Dr Macrobin, that the lecture should be published. Sadly, no copy of this lecture has so far

been uncovered.

The Aberdeen

Medico-Chirurgical Society was founded in 1789 by a group of medical students

who were dissatisfied with the quality of teaching at both the city’s

universities. However, in 1811 the

society evolved into a postgraduate medical community, due to the original

members graduating but continuing to attend meetings. Initially this situation was dealt with by the

creation of senior and junior sections of the society, but the junior component

withered and vanished, leaving only the postgraduates. Francis Ogston became a prominent member of

the Medico-Chirurgical Society and in 1848 he was one of two representatives of

the society attending a meeting in the Town House, which had been called for

the purpose of forming a Board of Health in the city. He agreed to act as a link to the Marischal

College Medical Faculty and he was appointed as the Board’s secretary. Also in 1848, Francis Ogston became a member

of the council of the Medico-Chirurgical Society.

As already

noted, one of Francis Ogston’s duties as police surgeon was to prepare an

annual statistical report summarising his case load for the previous 12

months. His 1850 report noted that he

had treated 117 individuals, 89 being in the department of the day patrol and 28

on the night watch. Most of the subjects

were male (79). But, by this year,

Francis Ogston had become so concerned with conditions in the Watch House that

he shared his views with the Police Commission.

When ten or twelve persons were confined in one cell, “the atmosphere

must become unwholesome”, he said. Some

commissioners thought that Ogston should have raised such issues much earlier,

but Francis was defended by the provost, and by Sheriff Watson, who pointed out

that he was only employed to deal with cases brought before him. The annual report for the following year made

clear two important characteristics of the range of situations presenting

themselves: more than half the cases involved drink at the time of referral and

some of the police out on patrol themselves got injured in the line of duty.

The Boys’

and Girls’ Hospitals

Formal

provision for the education of poor boys in Aberdeen was instituted in 1768

with the formation of the Boys’ Hospital in the old house of Robert Gordon, the

Earl of Aberdeen. Initially 25 boys each

year were “clothed, maintained, and taught the ordinary branches of

learning”. Subsequently the number being

supported was doubled. A similar Girls’

Hospital for the education of 30 poor girls was instituted in 1829 at a house

in Upperkirkgate, support continuing to the age of 14 when the inmates were put

out to service. In 1830, Francis Ogston

was appointed as physician to the Boys’ and Girls’ hospitals. In that year his remuneration was £5. Each year from 1854, Francis produced a

summary report dealing with the overall picture of illness in the two

hospitals. In his first such report, he

noted that he had dealt with 17 cases among the boys and with 12 female

patients, with one male and three female deaths. There was a similar level of illness the

following year but with no reported fatalities.

Thereafter, Dr Ogston usually recorded generally good health amongst the

inmates of the two hospitals, usually without fatalities. The year 1862 was an exception. Three lads from the Boys’ Hospital went

swimming at Aberdeen beach but, tragically, got out of their depth. Two drowned and one was saved but one body

was washed away and not recovered.

Francis Ogston was called to the incident. The year 1870 saw another fatality of a lad

who died of complications to his heart following rheumatic fever. Francis Ogston continued in his medical

support to the two hospitals until 1886 when he submitted a letter of

resignation to take effect “as soon as it may be convenient to them (the

hospital managers) to appoint a successor”.

He had been in post for the remarkable time of 55½ years, between the

ages of 27 and 83! The regard of the

trustees and managers for their recently departed physician was minuted. “In accepting the resignation of the office

of physician to the Boys’ and Girls’ Hospital which Dr Ogston has held since

October 1830 the trustees and managers desire to enter in their minutes an

expression of their high appreciation of Dr Ogston’s services. At the commencement of his professional

career Dr Ogston was elected to the office he has now resigned and neither a

large practice nor the duties of the chair of medical jurisprudence in the

University of Aberdeen ever caused Dr Ogston to lessen that care which 55 years

ago he was called upon to bestow on the inmates of the hospital”.

The British

Association for the Advancement of Science meeting (1859)

In 1859, a new

Lord Rector, the Earl of Airlie, was installed at Marischal College, with the

students entertaining their champion at a banquet held in the recently completed

Music Hall buildings. Francis Ogston was

a top-table attendee and replied to the toast to “Medicine”. In September of the same year, the British

Association for the Advancement of Science met, also in the Aberdeen Music Hall,

under the presidency of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s consort. Francis Ogston was a supporter of the BAAS

and donated £5 to the fund raised to mount this important event. He was appointed to the committee organising

the programme for the Physiology sub-section and presented a paper on a curious

subject, cross-species suckling in mammals.

He cited a case of a greyhound suckling a kitten and also commented on

the practice in some West African tribes of young women who have never had

children being employed as wet nurses, milk secretion being stimulated by the

application of the irritant juices of a species of Euphorbia to the

breasts.

A brief

history of the Aberdeen Medical School

Almost from the

establishment of King’s and Marischal Colleges, each had employed a Mediciner,

and medical courses had been taught at both institutions, though there was

usually an antagonistic relationship between the two academic postholders. However, in 1818 a joint committee of the two

colleges was established, on the initiative of Marischal College, to conduct a single

medical school with an agreed curriculum.

The extent of collaboration, however, appears not to have been

deep. Each college still mounted its own

Chemistry courses, part of the medical curriculum. The Aberdeen Medical School only survived

until 1839 when the old antagonisms between Marischal and Kings led to the

abandonment of collaboration and each college then promoted its own medical

school. Along with the two seats of

medical learning in Aberdeen, there was also a flourishing private enterprise

provision of independent medical courses in the town, just as Francis Ogston

had himself conducted in both Chemistry and Medical Jurisprudence, before being

employed by Marischal College.

This sundering of the unitary medical school was probably the event which triggered the appointment of Francis Ogston as lecturer in Medical Jurisprudence in 1839. According to the biography, written by Prof McKendrick of Glasgow University, of the Professor of Medical Jurisprudence, published in the “Aurora Borealis Academica" (a compendium of pen-pictures of outstanding Aberdeen academics) in 1898, "Up to the time of his appointment to the lectureship in 1839 the number of graduates was small and all who had ambition and could afford it went to Edinburgh University with its famous medical school.. Ogston with Thomas Clark, then Professor of Chemistry (an MD graduate of Glasgow University), did much to improve the educational facilities in Aberdeen, to raise the standard of teaching and to make the examinations more thorough. He (Francis Ogston) had the satisfaction of seeing his labours crowned with success". Clark had been appointed Professor of Chemistry in 1833, but in 1843 his health broke down; thus, their collaboration must have occurred between 1839 and 1843. In 1883, when Francis Ogston retired from the University of Aberdeen, it was noted that he was the last surviving link with the founding of the Marischal College Medical School.

In the newly

reinstated competition between the two colleges for medical students in 1839,

King’s was clearly at a locational disadvantage, being seated in the rather

small borough of Old Aberdeen about two miles from the Aberdeen Royal

Infirmary, where clinical teaching, of necessity, was conducted. Marischal College’s location was in the much

larger settlement of the New Town and within easy walking distance of ARI. King’s sought to remove this disadvantage by relocating

much of its medical teaching to the New Town.

In 1842, King’s College advertised its forthcoming medical courses in

the Aberdeen Journal. “Chemistry will be

taught as formerly in King’s College; Anatomy and Surgery at No 6, Flourmill

Lane and the other classes in the Medical School at Kingsland Place till 1st

January after which all classes will be taught in the Medical School presently

erecting in St Paul Street”. This really

was taking the fight to the enemy. St

Paul’s Street was situated off Gallowgate, a mere stone’s throw from Marischal

College on Broad Street.

During the

1850s, bickering, antagonism, non-cooperation and even frank obstruction were

the order of the day for relations between the two colleges, but outside forces

were tiring of this perpetual low-level warfare. The Aberdeen Herald, in an opinion piece in

1853, summarised this external frustration.

“For nearly a score years we have been labouring, in season and out of

season – occasionally, we doubt not, greatly to the annoyance of some of our

readers – to get rid of the scandal of two rival Universities, or Colleges, or

whatever they are to be called, running each other down, and by their

competition for the business of manufacturing Degrees, bring discredit on the

cause of learning in the north. Every

legitimate weapon that came to our hand we have freely used; argument till we

were tired of arguing; remonstrance till we felt ourselves getting angry; and

ridicule to the full extent permitted in dealing with grave and dignified

Professors, even although they had laid themselves open to any freedom of

comment by their silly jealousies, hostile attitudes, and ill-disguised

attempts at corporate and individual aggrandisement in the paltriest of all

directions – pecuniary profit”.

By 1853, the

two institutions of higher learning had established a joint committee to

examine future collaboration. It

reported that there should be a full merger between both of the universities,

in terms of their degree-awarding powers, and between the two colleges, in

terms of their teaching programmes, though both sets of buildings, in the old

and new towns, were proposed to be retained.

The Senatus of Kings College passed a resolution endorsing amalgamation

on the following principles. 1. Complete fusion of the two colleges resulting

in single faculties of Arts, Laws, Medicine and Divinity. 2.

Arts to be taught solely at the Aulton site, other faculties to be

taught as appropriate, but that the seat of the University should be at King’s

College. Because Marischal College did

not object to this proposal, the Aberdeen Herald took that as tacit acceptance,

but predicted that the proposal would generate public hostility. More likely, Marischal College did not deign

to notice the proposal.

This merger

proposal would, of course, have solved the problem of the competing medical

schools, though there were some who saw such an outcome as bad, through the

loss of competition, which they deemed to be unhealthy. It was even suggested that the Infirmary

might then be prompted to start its own rival teaching facility. Meanwhile, the Marischal College medical

school was winning the fight for students.

The Aberdeen Herald at the end of 1856 reported that “The friends of

this School will be glad to learn that it is in a more prosperous condition now

than it has ever been previously – no fewer than 116 students having been

enrolled during the present Winter Session, many of whom come from a distance”.

Then, the University Commissioners in

1858 settled the argument in proposing the full merger of the two institutions

with the single medical faculty to be located at Marischal College. It is interesting that although Francis

Ogston was a public, bitter and implacable opponent of the loss of Arts

teaching from Marischal College, he was entirely silent on the future location

of the medical school.

The “Fusion”

of 1860

The merger of

King’s and Marischal colleges in 1860 to create the University of Aberdeen

proceeded from “The report of Her Majesty’s Commissioners appointed to inquire

into the state of the Universities of Aberdeen with a view to their Union”

published in 1858. It was presented to

Parliament and approved, its provisions being enacted through the Universities

(Scotland) Act of 1858, which passed on 2 August. A Head Court of the inhabitants of the city

was called at the Court House in mid-May at which the Universities (Scotland)

Bill was discussed. Francis Ogston was

an attendee. The main structural recommendations of the University

Commissioners were that only the Faculties of Law and Medicine (which included

Botany and Chemistry) should remain at Marischal College, the Faculty of Arts,

along with Divinity should be based at Kings and a new library should be

constructed at the Aulton site. Francis

Ogston had graduated MA from Marischal College, the loser in the

rationalisation of arts teaching and he clearly felt an attachment to Arts

provision at his alma mater. He,

along with four other senior academic staff at Marischal College organised a

petition, in June 1858, opposing the move to relocate arts instruction. A citizens’ committee then solicited

subscriptions for the defence of Marischal College to which Francis Ogston

donated 3gns. At the end of January

1859, the Aberdeen Herald and General Advertiser described Francis Ogston as

one of the protest leaders campaigning for the retention of arts teaching at

both the Kings and Marischal sites.

The academic

opposition to the merger proposals was mainly expressed by the staff at

Marischal College and the division of views amongst the teaching community

spilled over into the election of the Dean of Faculty at the beginning of March

1859. Two candidates were put forward,

Alex. Thomson, Esq of Banchory, the retiring dean, proposed by Rev Dr Pirie,

and Sir Thomas Blaikie, proposed by Principal Dewar, the two candidates falling

on opposite sides of the fusion debate.

A vote was taken which produced a split decision with seven votes for

each candidate, Francis Ogston casting his vote in favour of Sir Thomas. Mr Thomson attended the meeting and attempted

to vote – for himself – to break the impasse but Principal Dewar declined to

accept his participation. Instead, Dewar

cast his deciding vote for Sir Thomas, elevating him to the role of the new Dean

of Faculty. The principal’s decision was

disputed by Thomson and his supporters, but the outcome stood. Sir Thomas Blaikie was also the chairman of

the Citizen’s Committee for the defence of Marischal College.

It was not just

the senior academics at Marischal College who took exception to the

proposals. In general, the citizenry of

Aberdeen was antagonistic towards the recommendations, which appeared to them

to be emasculating their university, making it subsidiary to the campus at

Kings College in Old Aberdeen, the much smaller settlement, and removing arts

teaching from the site which was most conveniently placed for the attendance of

the general population. Their views,

along with those of the academics at Marischal and of the Town Council, were fully

expressed at a second Head Court, held in March 1859. This meeting was called by the provost, with

the concurrence of the Town Council “To take into consideration the resolutions

of the Universities (Scotland) Commissioners, as regards the universities and

colleges of Aberdeen, and to express such opinion, and adopt such measures

thereanent as may appear to be proper and expedient”. Feelings were running high in the New

Town. So many people turned up for the

event that the Court House could not accommodate everyone, and the meeting was

relocated to the North Church. Not all

attendees were opposed to the reform proposals.

A group of students from Kings College were in favour of them and formed

a disruptive element in the proceedings, which were attended by an estimated

1600 – 1700 people. Francis Ogston, of

course, was present and a resolution opposing the abolition of arts teaching at

Marischal College was passed.

Many further

attempts were made to get the proposed reforms revised but without

success. In January 1860, the Ordnances

of the new university were published in the Edinburgh Gazette, while the old

ordnances were still under appeal to the Privy Council, but outwith Aberdeen

there was no mood to change the proposals.

As the Aberdeen Herald and General Advertiser commented at the time, “… there

is no indication of any change in the localization of the fused Classes of

Arts. That they are to be fused is

obvious from the superannuation of several professors …”. This newspaper was not supportive of the

Marischal College academics, suggesting that their actions were damaging their

own interests by fighting the fusion plan.

The displaced professors were treated generously, being retired on full

salary during life and the older of the two professors in each subject

generally being chosen for removal.

However, a contrary and particularly fateful decision was taken in the

case of the two professors of Natural Philosophy (Physics). Professor James Clark Maxwell, the much

younger incumbent at Marischal College was, anomalously, given the

heave-ho. He went on to become one of

the most famous physicists in the history of the discipline. Francis Ogston survived the cull, his

position being unique, and he was retained in the Chair of Medical

Jurisprudence, in which post his salary was to be £222 per annum.

Even after the

fusion became a reality, protests against the removal of arts teaching from

Marischal College continued. In February

1861, a vote was taken in the Senatus Academicus, where Francis Ogston was a

prominent member, proposing the removal of arts teaching to New Aberdeen (ie to

Marischal College) but it had to be set aside when the University Commissioners

declined to sanction the move. Francis

Ogston was appointed as an assessor to the University Court by Senatus in the

same year, in which body he proposed a motion inviting the Court to express an

opinion that Marischal College was the preferable site both for arts teaching

and as the location for the new library.

But such protests had reached the end of the road. An amendment to Ogston’s motion, “to the

effect that it is incompetent for the Court to entertain the motion in respect

that the Commissioners have fixed the site both of the Arts classes and the

Library by an ordinance approved of by Her Majesty in Council and with which

the Court is bound by statute not to place itself in conflict”. The amendment was passed by four votes to

two. Perhaps the final protest by

Francis Ogston concerning the ramifications of the fusion occurred in 1863. At the University Court in April of that

year, Francis supported the view that if a new library could not be located

mid-way between King’s and Marischal, it should be located in the Marischal

College buildings. Francis returned,

like a dog with a bone, to the library theme at a further meeting of the

University Court in October of the same year.

A proposal was made to convert the hall at Marischal College for dual

use; library and public meeting place. This

was opposed in a motion by Mr Webster, though Francis Ogston pointed out that

such a situation held at Trinity College, Dublin. It appears that Francis, who was generally

thought of as a mild-mannered man, did not pull his punches in attributing

blame for the lack of good library accommodation as reported by the Aberdeen

Journal. “…he was of opinion that the

present defective accommodation in the Library is owing in some degree to the

grudging and illiberal spirit of the Librarian and others in King’s College”! Mr Webster’s motion was carried, and the new

library was built in Old Aberdeen.

Francis Ogston’s term as Senatus Assessor on the University Court

expired in 1865.

The

reconstituted, merged university continued on its way, with Marischal College

as the academic home of but two faculties, albeit the important ones of Law and

Medicine. It will perhaps be surprising

to those familiar with the modern University of Aberdeen that in 1860 there was

no Faculty of Science and subjects such as chemistry, botany and natural

history, all relevant to the study of Medicine, were taught at Marischal. Although much needed accommodation for the

burgeoning disciplines of Medicine and Science was thus freed at Marischal

College, the problems associated with this restricted site in the middle of the

New Town would soon return to trouble the nascent institution. The Faculty of Science was created in 1893.

Francis

Ogston acquires a new and prestigious residence

By the year

1865, Francis Ogston had developed a substantial private medical practice and

on graduation his son Alexander, now aged just 21, was appointed as his

assistant to help with this work.

Alexander continued in this role for eight years. Also in 1865, Francis sold two houses, “…

front and back with the shop at the front in Broad Street adjoining the

entrance and Court of the University buildings, as possessed by Dr Ogston and

his tenants”.

Likely the two

houses were 84 Broad Street and 2 Gallowgate which had been owned by the Ogston

family for many years. A year later, in

1866, Francis Ogston moved house from 18 Adelphi to the prominent and

prestigious address of 156 Union Street and the Adelphi town house was also

subject to disposal. In those days,

Union Street was a popular domicile with prominent Aberdonians, especially

those in the medical profession and this change of accommodation must have

helped with advertising the presence of the two medical Ogstons to potential

patients. Further, in 1866, son

Alexander was appointed by the University Court as an assistant to his father

in his role as Professor of Medical Jurisprudence, a post which was nominally

shared with Prof Dyce Brown of Materia Medica.

This arrangement continued until 1869 when the shared assistantship was

separated into two components by order of the Privy Council. Alexander was then appointed Assistant

Professor to his father, Francis, for the academic year 1869 – 1870 in Medical

Jurisprudence and continued in this role until 1873.

Francis

Ogston and the cholera epidemic of 1865 - 1866

Cholera is

caused by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae which infect the

small intestine and cause the production of large quantities of watery

diarrhoea, with associated loss of electrolytes, which frequently leads to

death if untreated. It is usually spread

by drinking water contaminated with the faeces of infected persons. Although this malady did not reach British

shores until the major epidemic of 1831 – 1832, it had probably existed in

human populations for 1,000 years or more.

This first British epidemic spread to all parts of these islands and

killed perhaps 40,000 people, including 10,000 in Scotland. A second epidemic occurred in 1848 – 1849,

probably entering via the port of Leith. Altogether about 53,000 deaths

resulted from the recurrence of this intestinal infection. A further outbreak from a new source took

place in 1853 – 1854, with at least 20,000 fatalities. Thus, when a fourth outbreak was detected on

the south coast of England in 1865, which had probably originated in Egypt,

there was a good deal of anxiety and even panic that this dreaded scourge,

especially of those living in poor housing conditions, had returned. The Lord President of the (Privy) Council

sent a circular letter to local authorities warning them of the necessity to

take precautions against the possible arrival of cholera. A further directive required the appointment

of local Officers of Health to supervise precautions against cholera, isolation

and treatment of victims and local management of the response to any epidemic.

In Aberdeen the

Police Commissioners met to consider what precautions should be implemented and

initially their attention was drawn to the need to quarantine vessels arriving

at the port and the need to provide for the hospitalisation of affected people

should cholera appear. Aberdeen Royal

Infirmary managers were approached concerning provision of hospital

accommodation, but they denied it was their responsibility. The West Prison was then suggested as a

possible cholera hospital and Francis Ogston, together with the city architect,

Mr Smith, were dispatched to assess its suitability. Meanwhile, cholera was steadily advancing

through the country. It had reached

Southampton in October 1866 and was soon after reported in Sheffield and

Epping. Later it was also rife in

London, especially in the crowded and insanitary conditions of the East

End. Unfortunately for the Aberdeen

Police Commissioners, the County Prison Board rejected the request to employ

prison accommodation for cholera isolation and another suitable building had to

be found. By August 1866 the disease was

reported in Montrose and there had been unexplained deaths in Fraserburgh,

which Francis Ogston was despatched to investigate. It proved to be cholera and in the first two

weeks of August this northern fishing port had experienced 73 cases of cholera

and 12 deaths.

Francis Ogston,

ever willing to serve the public interest, agreed to take temporary medical

charge, at the request of the Police Commissioners, should cholera break out in

Aberdeen. Some important arrangements

were finally agreed in mid-August. The

money (£200) for salaries associated with the officer of health function was

committed, of which it was anticipated the officer of health would take

half. After an initial delay, the

appointment of Francis Ogston as the Officer of Health was announced. He was already familiar with police work and

was easily the best-qualified candidate.

The provost spoke in his favour.

There had been some concern that Francis Ogston would be unable to

devote sufficient time to the role in an emergency, due to his other

commitments, though the Commissioners also worried that his present salary (30gns)

as police surgeon was too low for the work required. The Fever Hospital at the Infirmary was

cleaned out, fumigated and lime-washed to make it suitable for use, if required,

as a cholera hospital. It contained two

male and two female wards in which 40 to 50 patients could be treated. A litter to carry patients had been constructed

and men retained for carrying it. Two

male and two female nurses were also engaged.

Francis Ogston made a selection of doctors to take charge of districts

and experienced medical students to conduct house-to-house visitations. Arrangements were also made with druggists in

different districts of the town to supply medication at no cost, if consulted

about bowel complaints and arrangements were made for making the statistical returns

requested by the Board of Supervision.

Twelve additional scavengers (street cleaners) were recruited to clear

the worst streets, lanes and closes in the town of rubbish and filth, prior to

them being washed down. The police were

alerted to report nuisances to the Superintendent, so that he could deal with

their removal. He had also reported that

the licensed lodging houses in the town were in good condition but, as a

precaution, he had issued an order for them to be lime-washed, except where

that operation had been recently done. Finally,

Francis Ogston was provided with statistical information to guide him on

dividing the town into districts for supervision and control, should cholera

arrive. The disease possibly arrived in

Aberdeen about 18 August 1866 when a woman, who had been in contact with a

seaman, developed severe diarrhoea and expired.

At that time, it was difficult to diagnose the condition with certainty

because there were other diseases (such as “British cholera”) which mimicked

the symptoms of Asiatic cholera. Although

there were eventually about 64 deaths from Asian cholera in Aberdeen during

this epidemic, the arrangements made for managing the outbreak were fairly

effective. In mid-September 1866,

Francis Ogston made a precautionary visit to both Edinburgh and Glasgow to

evaluate the measures introduced by those cities to counteract the

cholera. He reported to the Police

Commissioners on his return that Aberdeen’s measures were at least the equal of

those introduced in Scotland’s two largest conurbations, no doubt stirring

Aberdonians’ civic pride in the process.

By the end of September 1866, the threatened crises had effectively

ended, though sporadic cases recurred until the end of the year, when a violent

snowstorm seemed to break the chain of transmission. Altogether in Scotland there had been about

1,170 deaths.

During January

1867, Francis Ogston made a report to the Police Commissioners on the recent

cholera epidemic. In it he made a series

of recommendations for the future protection of the city should there be a

return of the dreaded malady. These

recommendations were based closely upon the conduct of the authorities and the

officer of health during the local outbreak of the previous year. They were as follows. 1. The

division of the city into convenient and manageable districts. 2. The

printing of handbills setting forth such plain rules for the preservation of

health as might be useful to the community under existing circumstances. 3. The

arrangement of convenient stations throughout the city for the giving out of

appropriate medicines on application.

4. The appointment of a staff of

medical house-to-house visitors. 5. The appointment of district medical

officers. 6. The appointment of a Sanitary Inspector to

carry out the orders of the Nuisance Removal Committee on the reports of the

medical officer and the district medical staff.

7. The procuring of stated weekly

returns of the health of the city.

8. The procuring of a cholera

hospital with the appliances necessary for the removal and treatment of the

sick. 9.

The obtaining of a sufficient staff of nurses for the duties of the

hospital and the charge of patients at their own homes. 10.

The finding of a house of reception for healthy persons requiring

removal from unhealthy or infected localities. At the same meeting, the Dean of Guild

publicly acknowledged the leading role that Francis Ogston had played. Francis received a fee of 120gns for his work

and this figure was later used by his son, Alexander, to derive his fee (2gns

per patient) for work during an epidemic of smallpox. As will be seen, this proved to be highly

controversial.

Francis

Ogston and the North of Scotland Banking Company

This

Aberdeen-based bank was incorporated in 1836 and Francis Ogston’s association

with the firm went back at least to 1846 when he was listed as a member of the

company. That status was maintained

until 1853 but in 1854 he was elected to the bank’s board of ordinary

directors, an appointment which lasted for a year but with the possibility of

re-election for a further term of office.

He joined the board again in 1856 and then served continuously up to and

including 1867. No evidence has been

found that he served after that year. He

would then have been 65 and may have decided to retire from this commercial

position. Francis had a sharp intellect

and came from a family with strong commercial instincts and appeared to find

the challenges of a bank boardroom well within his capabilities.

Francis

Ogston and Queen Victoria.

No direct

evidence has been discovered, including in the Royal Archives, that the monarch

ever sought help from Francis Ogston for either her relatives or her

staff. However, his son Alexander wrote

that his father, Francis, had had a number of interviews with the Queen,

concerning illnesses to both her family members and estate employees, and that

he too had initially found that holding a conversation with Her Majesty had

been a nervous experience, though the feeling passed with time. Alexander also wrote that his father did not

want his Royal connection publicised, and no indication was given of the time

interval during which these consultations occurred, though they probably took

place after 1861 (when the Prince Consort died) and before 1880 (when Francis

Ogston started withdrawing from medical activities).

Francis

Ogston and charity

As he got

older, Francis Ogston became more involved in charitable giving, with a strong

emphasis on local causes in the North-East of Scotland, the most prominent of

which were the two main hospitals, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and the Royal

Aberdeen Children’s Hospital. In 1885,

it was reported in the Evening Express that Professor F Ogston continued to

subscribe 5gns annually to ARI and thus qualified to be a life manager of the

institution. He also made one-off

donations to the Children’s Hospital, for example, a 1gn donation in 1877. Francis was also reported on several

occasions as channelling donations from his private patients to ARI, for

example £5 given by “a country lady” in 1874.

The Aberdeen Asylum for the Blind also received at least one

contribution from Francis Ogston.

The Professor

of Medical Jurisprudence was also moved to support acute needs such as the

Indian Famine of 1877, the famine in Asia Minor in 1874 and the Chicago fire of

1871. Nearer to home, he also

contributed to appeals supporting unemployed operatives in Aberdeen in 1868 and

1885 and he was a member of the Association for Improving the Conditions of the

Poor. Although most of his charitable

giving related to human distress, he occasionally donated to other causes, such

as the Aberdeenshire Volunteer Artillery and Rifle Association, the Aberdeen Art

Gallery and Museum and the Imperial Institute, which promoted trade links with

the Empire.

Francis

Ogston and the Church

Francis Ogston

was a committed churchman and from at least 1869, he was an elder and a

prominent member of the congregation at the West Kirk of St Nicholas, acting as

convenor of the committee appointed to find a successor to the minister of the

West Kirk in 1869, being a member of the Aberdeen Church Extension Association

and the committee set up to raise funding for the restoration of the transepts

at St Nicholas in 1876.

St Nicholas Kirk

George

Cadenhead, Procurator Fiscal and the spat with Dr Angus Fraser

The need for

doctors to have a clear understanding of the principles of Medical

Jurisprudence was well illustrated by an incident which took place in

1878. The same event also illustrated

the need for doctors, or indeed anybody, to control their passions when a clear

view of a complex issue is required, unobscured by the descent of a red mist of

irrationality. At the time George

Cadenhead, Francis Ogston’s brother-in-law, was Procurator Fiscal for Aberdeen,

a role his father, Alexander, had previously occupied’

Dr Angus

Fraser, an Aberdeen GP who had been born in the city and lived at 232 Union

Street, was called out one morning in 1878 to see one of his patients who had died

unexpectedly during the night, having previously seemed in good health. Fraser’s judgement was that this death was due

to natural causes and would not need to be referred to the Procurator Fiscal. Fraser still felt that it was wise to carry

out a post-mortem examination to establish the cause of death and the widow

agreed to this proposed course of action.

He planned to carry out the procedure himself, two days hence, but did

not inform the Procurator Fiscal of his intention. Meanwhile, the Procurator Fiscal was notified

of this sudden death from another source and, being ignorant of Fraser’s

arrangements, gave an instruction to Francis Ogston, the Police Surgeon, to

carry out a post-mortem examination.

Francis Ogston delegated the task to his second son, Frank, who was

acting as his assistant at the time.

Frank completed the procedure on the day following the man’s demise and

concluded that his was, indeed, a death due to natural causes. As far as the Procurator Fiscal was

concerned, that ended his interest in the matter.

The Aberdeen GP

was extremely miffed when he discovered that events had overtaken his plan and

he sought to take out his anger on the Procurator Fiscal, whom he held

responsible for the disruption of his intentions, with an exchange of angry

letters to which George Cadenhead, the PF, retaliated in kind, the difference

being that Cadenhead understood exactly the ground which he occupied, whereas

Fraser could not see beyond, as he saw it, the subversion of his plan. He continued to rage. The simple fact was that Cadenhead could

legally nominate anyone he cared to, to perform the post-mortem, provided that

person was qualified to carry out the work, and Frank Ogston was so qualified. Dr Fraser considered that he held senior

status over Frank Ogston, which may or may not have been true, but this was

irrelevant. Is it possible that Fraser’s

anger was due to the base motive of losing the fee for the examination? Is it also possible that he suspected a

degree of nepotism that the work had been directed to the Ogstons, since

Francis Ogston was the widower of George Cadenhead’s sister?

Angus Fraser

made a number of tactical errors, in addition to misunderstanding the

legalities of the case. He released the

correspondence to the press, which gleefully published this tasty exchange,

perhaps thinking it would vindicate his stand.

He also forgot the name of his patient, submitting an incorrect appellation. Further he suggested to the PF that there

were suspicious circumstances surrounding the death when none existed. George Cadenhead did not hesitate to

discomfort his antagonist with his cutting responses to Fraser’s accelerating

ire, as the following excerpts from the correspondence show.

“This would

have been my resolution even if your communications had shewn that the

discussion was likely to be conducted on your side with high logical

ability”. “Pray don’t add to other

dialectical mistakes that of supposing that by this style of answer I either

take or intend to give any personal offense”.

“Lastly, I would strongly recommend to you to submit our correspondence

to some impartial person or persons unprejudiced by the professional grievances

– which I think is the main motive of your letters – and see what they may say

about it and be guided by their opinion.

If you do publish, I can tell you there are several points which will

provoke amusement in your readers – beginning with the family medical attendant

being ignorant of his patient’s name and ending with the curious process by

which you seek to convict me of improperly dealing with the present case as one

of suspicion. The correspondence will

certainly be amusing. You will assuredly

make sport for the Philistines and you may even succeed in bringing down the

house as Samson did”.

The “Medical

Times and Gazette” politely put Dr Fraser in his place. “We regret exceedingly that such a

correspondence as this was ever laid before the public …”. “It is a pity that Dr Fraser was not present

at the post-mortem, but his own statement of his own conduct puts him entirely

out of court and the subsequent correspondence does not improve matters”.

Lectures on

Medical Jurisprudence

In 1878,

Francis Ogston reached the age of 75. He

had been lecturing on Medical Jurisprudence since before 1839, a period in

excess of 39 years. During this long

interval, he had revised and expanded his lecture course many times and felt

confident that his work was worthy of publication. This scholarly treatise was very much a

family enterprise, written by Francis Ogston, edited by Frank Ogston, advised

by George Cadenhead, Procurator Fiscal for Aberdeen and illustrated with line

drawings by James Cadenhead, only son of George Cadenhead, who became an artist

of significant status. The book was

published in London by J&A Churchill in 1878 and quickly became established

as a seminal work on medical jurisprudence both nationally and internationally

and especially with reference to Scotland with its own legal system. The work retained the lecture course

structure with 45 chapters, each one lecture in length, plus two appendices,

more than one lecture being required for some topics. The subjects of discussion were: Medical evidence,

Age, Sex and doubtful sex, Personal identity, Impotence and sterility,

Defloration, Rape, Sodomy, Pregnancy, Delivery, Birth, Criminal abortion,

Infanticide, Insanity, Feigned, factitious and latent diseases, Death,

Medico-legal inspections, Homicide, Wounds, Death by drowning, Death by

hanging, Death by strangulation, Death by suffocation, Death from cold, heat,

lightning and starvation, General toxicology.

Reading the

work today, one is struck by its comprehensive nature (it runs to over 650 pages)

and its erudition. In 1883, on his

retiral from the University, Francis Ogston’s successor to the Chair of Medical

Jurisprudence, Matthew Hay, said of his predecessor, “Dr Ogston was a man of

venerable age and a man who held a very high reputation in his profession, and

they had every reason to believe for he supposed that it was in the knowledge

of almost all of them, as well as of the professors, that Dr Ogston was held as

a first professor in his special department.

The latest work he had published had been spoken of not merely in

Scotland and England but throughout the whole of Europe as a work on

Jurisprudence of the very highest class”.

Francis Ogston's Lectures on Medical Jurisprudence

The death of

Francis Ogston

Francis Ogston

died on 25 September 1887 at his home, 14 Albyn Terrace in Aberdeen’s upmarket

West End. He was 84. He had been declining in health for some time

and had been noticeably ill for about six weeks. According to the Aberdeen Journal the

immediate agent of his death was a sudden “heart affection”, though at the

registration of death the cause given by Dr A MacGregor was simply “old

age”. Francis’ daughter, Jane (Mrs

Cowan, wife of Professor Henry Cowan) was with him at the end.

Francis Ogston (1803)

The funeral of

Francis Ogston was a very formal and public affair and was attended or observed

by many members of the Senatus and Court, academics and students of the

University, together with doctors from the surrounding area and of the

citizenry of Aberdeen. This was a