How was John

Michie appointed as Balmoral Factor against the hostility of Donald

Stewart?

John Michie

Dr Alexander

Profeit was Queen Victoria’s second commissioner at Balmoral between 1875 and

1897. He died in office after declining

in health, including in his mental capacity, for some years. This made life very difficult for John

Michie, due to the Commissioner’s erratic and unreliable behaviour. It is not clear if John Michie had any

aspirations to succeed Alexander Profeit in the top job on the Royal Deeside estates,

though in 1897 he was almost 44, had accumulated 19 years’ experience on

Deeside and would have been a credible candidate for the role of

commissioner. At the start of 1897 John

Michie was unaware that it was planned to replace Dr Profeit and by mid-February

James Forbes had been offered, and had accepted, the role of Commissioner at

Balmoral. John Michie had been passed

over for the top job at Balmoral, but was that because he was considered

unsuitable in some way, or because he had not made clear that he had

aspirations to become commissioner, or simply because a highly qualified

alternative candidate had been uncovered?

James Forbes,

the new commissioner, was an ambitious man in a hurry. He was nine years

younger than John Michie and with no experience of the Deeside estates, but

with factorial experience elsewhere.

However, Forbes’ own aspirations led to him resigning in 1901 to go to

an even bigger role at Blair Atholl. The

question therefore needs to be posed, “Why was John Michie considered for the

role of factor on the Royal Deeside estates in 1901, when he had apparently

been passed over for the same role in 1897”?

One obvious difference between the years 1897 and 1901 was that at the

earlier date, Queen Victoria was still on the throne, though aged and declining

in her own faculties, and at the latter time her son, King Edward VII, had

ascended to the throne.

Blairs Castle

There was

another issue which may have come into consideration when evaluating John

Michie as a potential commissioner and that was his difficult relationship with

Donald Stewart, the revered head Keeper, still in post, though aged 71 in

1897. He eventually retired in

1901. Donald was respected by the senior

members of the Royal family due to his long and loyal service at Balmoral, right

from the start of Royal possession of the estate in 1848, through 1897 and

beyond. It was not just a matter of

loyalty and length of service. Queen

Victoria had a close relationship with Donald and his family, and many times

visited the Stewart house to take tea and sample Margaret Stewart’s scones and

jam. King Edward had been tutored in the

art of deer stalking by Donald Stewart and, like the monarch’s mother, was

close to this senior servant.

To appreciate

just how close and influential was the position of Donald Stewart with the

Royal Family and the Court, reference can be made to the celebration of his

achieving 50 years of service at Balmoral in 1898. The Aberdeen Journal’s description of the

event encapsulates its significance.

“When Donald Stewart had served 50 years in the Queen’s service in 1898,

he received a number of gifts.

Personally, from Her Majesty he received a fine mantlepiece 8-day clock

inscribed as follows. “To Donald

Stewart, head forester at Balmoral in remembrance of his faithful service for

50 years to the Queen and Prince Consort – VRI October 8 1848 – 1898”. The bigwigs from the Court joined in with the

Royal sentiment by presenting Donald with an inscribed silver salver. “Donald Stewart, 8th September

1898, Entered the Queen’s Service, 8th September 1848, From, Colonel

the Right Hon Sir Fleetwood J Edwards KCB, Lieut – Colonel Sir Arthur Bigge KCB

CMG, Colonel Lord Edward Pelham Clinton KCB, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Edmund

Commerell GCB VC, Captain Walter Campbell MVO, Colonel Lord William Cecil MVO,

Colonel the Earl of Strafford KCB KCMG VC, Major the Hon H Legge MVO, Captain

Fritz Ponsonby MVO, Lieutenant-Colonel A Davidson MVO, Lieutenant J Clark CSL

CVO, Sir James Reid Bart KCB, Mr Mather MVO.

There had been

a long-running disagreement, at least since 1892, between John Michie and

Donald Stewart over the need to keep down rabbits which caused substantial

damage to young trees in the Balmoral plantations. The keepers, probably backed at least

surreptitiously by the hunting afficionados within the Royal family, often paid

mere lip service to orders to kill down the hungry lagomorphs. Densely planted plantations offered poor

hunting country, whereas more natural, open forests gave much better

sport. Further disagreements arose

between Michie and Stewart concerning staffing, especially the appointment of

the poorly qualified Albert Stewart, Donald’s son, to the role of foreman of

John Michie’s squad of workmen at Birkhall, apparently without reference to the

head wood forester. However, the most

serious bone of contention between the two was dug up and fought over in 1897,

when Donald Stewart accused John Michie of illegally selling salmon taken from the

Dee at Balmoral. The unproven accusation

was never withdrawn by Donald, no apology was made, and the matter remained

unresolved, no doubt simmering malevolently below the surface of normal human

discourse. Although never a credible

candidate himself for commissioner, Donald was a person whose views mattered at

Balmoral, and it later emerged that Donald had at some stage made his negative

opinions of John Michie known privately to the monarch’s representatives, or

even the monarch himself. This difficult

relationship with Donald Stewart might have been a serious impediment to John

Michie’s candidature if Stewart’s view were communicated before mid-1901.

One factor which undoubtedly helped John

Michie’s candidature was the close and supportive relationship that he

established with the incoming commissioner James Forbes. Michie, without a hint of rancour at being

passed over, set out to make James Forbes’ transition to Balmoral as smooth as

possible. John’s experience of the

geography, history, servant complement and commercial relationships of the

estate, which he made freely available to his new boss, clearly impressed James

Forbes. The new commissioner came to

rely on Michie for guidance as to how matters had been conducted on the estate

and, in return, Forbes delegated freely to the head wood forester on matters

much wider than the management of forest business activities. This close relationship, which extended to

the social sphere, led in July 1901 to James Forbes confiding in John Michie

that he (Forbes) was leaving to take the top job at Blair Atholl and that he

was recommending that John Michie should be his successor. Forbes may even have made his recommendation

directly to King Edward VII when he sought leave to resign office. While such an endorsement was no guarantee

that John Michie would be the successor, it would certainly have been

important. On this occasion, John Michie

did inform the King, through Sir Dighton Probyn that Mr Forbes had told him of

his impending transition to a new charge and that he (Michie) hoped that His

Majesty “… will consider him to succeed”.

(RA PPTO/PP/BAL/MAIN/OS/838 letter dated 1 July 1901 from John Michie to Sir

Dighton Probyn).

Circumstantial

evidence suggested that James Forbes had been warned about the tensions which

existed in the relationship between the head keeper and the head wood

forester. Forbes would also have been

aware of the status that Donald Stewart enjoyed both with Queen Victoria and

with her eldest son. James Forbes had a

difficult path to negotiate between the two antagonists. However, while James Forbes often seemed to

appease Donald Stewart, for example by giving him representation on committees

which he was barely qualified to hold, he was not taken in by the old man’s

views. In October 1901, James Forbes in

a letter to Sir Dighton Probyn (RA) wrote, “Donald Stewart is a very old and

fanciful servant and I agree this case is quite an exceptional one and may

safely be dealt with as such.” This may

have been a reference to the granting of a generous pension of £100 pa to the

former head keeper (RA PPTO/PP/BAL/MAIN/OS/844 letter dated 1 October 1901 from

James Forbes to Sir Dighton Probyn).

John Michie’s

relationship with Donald Stewart was not uniformly difficult. There were several periods between bouts of hostility

where the interactions between the two men were at least cordial. Without doubt John Michie did not harbour

grudges, as his behaviour towards the retired head keeper showed in the period

1902 – 1909, that is, after Michie’s appointment as factor and before the death

of Donald Stewart. But, as will be seen,

the same cannot be said for Donald Stewart.

The atmosphere

between the newly-appointed factor and the just-retired head keeper appeared to

be tense in late 1901 to early 1902 as shown by the entries in John Michie’s

diary – not so much in what he said about Donald Stewart but in what Michie

omitted to record. On 28 November 1901,

John Michie wrote “Meeting privately of a few representative men at the Croft

to consider what should be done to give effect to a desire to show respect to

Mr. & Mrs. Forbes on their leaving for Blairatholl. Resolved to call a

public meeting at Abergeldie on the 9th prox”.

Michie was silent on the fact that The Croft was Donald Stewart’s

residence and that the meeting must have been called by him, which was a

presumptuous and even provocative act.

When the leaving party was held for James Forbes, with John Michie in

the chair, he again managed briefly to record the occasion without mentioning

Donald Stewart’s prominent role. “Mr

Forbes send-off cake & wine banquet held within the Ballroom at Abergeldie

Castle at which I presided. Rose bowl

and Candelabra, with a brooch to Mrs Forbes costing £109.7.0 was the

result. Of course, there were speeches

& there were a very representative gathering, including 14 from the Royal

Tradesmen in Aberdeen”. The most

memorable speech had been made by Donald Stewart who had been given the role of

presenting the very expensive brooch to Barbara Forbes, which he did in couthy

and humorous style much to the delight of the audience but especially to the

wife of the departing commissioner. At

that time, John Michie clearly wanted to scrub Donald Stewart from the script.

Donald Stewart

was installed in the Dantzig Shiel, five miles from the Castle, to spend his

retirement in semi-isolation from the running of the estate but in the company

of his wife, Margaret and his two daughters, Lizzie and Helena. This previously settled menage did not long

endure. In July 1902, Margaret Stewart

died, and John Michie represented the King and Queen at her funeral, placing a

wreath from the monarch on the coffin.

The inscription on this floral tribute read, ““From the King and Queen

Alexandra with sincere regret, in memory of a worthy wife and mother”. Margaret’s three brothers, two of whom were

in Royal service, attended to bid farewell to their sister. James Forbes also made the journey from Blair

Atholl for the funeral.

In January

1903, John Michie’s relationship with Donald Stewart was at least outwardly

normal. “Drove to the Danzig Shiel and

saw Donald Stewart who is in good health, but his daughter Lizzie is not very

well”. Lizzie was suffering from

tuberculosis and death again stalked the hinterland of the Dantzig Shiel. By early the following year, Lizzie’s

condition was worse. “Mrs. Michie went

to Danzig Shiel to see Lizzie Stewart who has been in worse health than usual

recently”. Thereafter calls by the

Michies at the Dantzig Shiel became more frequent. In February 1904, “… in the afternoon drove

to the Danzig to ask for Lizzie Stewart who is worse in health than usual. She is said to be so nervous that she cannot

be seen by visitors”. By this time Dr

James Noble was attending the Stewarts’ elder daughter regularly but all he

could do to help was to prescribe champaign to “sustain her strength”. At the King’s expense, Lizzie was sent to a

sanatorium down the valley in Banchory, but she died there in mid-June. Her body was returned to Ballater by train

for her funeral which was held two days after her demise. John and Helen Michie drove down to the

station to accompany the coffin back to Crathie and to attend the funeral,

which was conducted by Rev Sibbald, who had especially returned from holiday to

officiate.

John and Helen

Michie’s interactions with Donald Stewart seemed to continue on a friendly

basis in the early years of the new century.

In June 1903, “Donald Stewart drove Mr Mounsay down for the

evening”. The annual New Year shooting

match in 1905 was an opportunity for the Forbeses to visit both the Dantzig

Shiel and Baile-na-Coile. “Mr. & Mrs

Forbes of Blairatholl who have been staying at Danzig Shiel as the Guests of

Donal. Stewart came to the Shooting Match - the former participating in the

competitions. … Mrs Forbes & Helena Stewart lunched at Baille na Coille

with Mrs Michie”. In November 1905,

Helena Stewart acted as a local collector of cash and goods donations to a

“Great International Fair”, (patron HM the Queen) being held in Waverley

Market, Edinburgh, “in aid of funds of the Royal Victoria Hospital for

Consumptives (Patron HM King)”. This

hospital was established in Edinburgh in 1894 and the treatment of consumption

was a cause close to the hearts of the Stewarts.

Occasional

calls by the Balmoral Factor at the Stewart home continued. April 1906.

“In office most of the day but drove to Danzig Shiel in the evening and

arranged to have the passages papered, also the sitting room. Saw Donald Stewart and his daughter

Helena. Promised to send Ritchie the

foreman Painter up in a day or two's time with patterns to choose from”. Later the same year, John Michie made

arrangements to provide more support for the now declining Donald. “I went to the Danzig Shiel and arranged to

put a man to stay there in the bothy to attend to D Stewart's pony and do road

work in the locality. This on account

of Donald's age and more feeble health - he is 80 years past June”.

The following

year, 1907, there were further instances of John Michie’s friendly behaviour

towards the old, but still revered, retainer.

In January, “Drove my sleigh to the Danzig to visit old Donald Stewart

and delivered a 5 lbs packet of tea from Sir D Probyn who has sent 18 such

packets as Xmas presents - a piece of beef from the King's ox which is killed

annually for distribution among His Majesty's servants and others in the

district”. May saw the Balmoral Factor

meeting socially with Donald Stewart.

“Drove to the Danzig to fish with Donald Stewart & Arthur

Grant. The former landed one salmon, I

landed 3, Arthur who took the last chance had no luck”. And again, in November, “… called on Donald

Stewart at the Danzig on my way back where Mrs Mussen & her daughter were

at tea. I had a cup”.

By 1909, it was

clear that Donald Stewart’s mortal time was almost complete. Solicitous visits by the Michies became more

frequent to the Dantzig Shiel. “Drove

with Mrs M. to the Danzig afterwards and found Donald Stewart and his daughter

Helena well”. “Mrs. Michie visited old

Donald Stewart at the Danzig. He has not

been quite well recently but is better”.

“Drove to Danzig Shiel to see old Donald Stewart who is now in his

ordinary health. He had a turn of bad

breathing recently”. By July, John

Michie’s comments became more sombre.

“Drove (after office work in morning) to Danzig Sheil where saw old

Donald Stewart who appears to me to be nearing the end although his daughter

thinks him better in health recently”.

On 10 August, Michie’s diary recorded the inevitable news of the death

of the retired head keeper. “Donald

Stewart, retired Head Stalker died this afternoon at 4.20”.

However, all

the time that John Michie had been acting in a considerate and conciliatory

manner towards Donald Stewart, following his retirement, the latter had been

hiding a dark secret, which emerged from its hiding place at the time of

Michie’s own retirement in the summer of 1919.

On 27 May 1919, Sir Dighton Probyn wrote a revelatory missive to Sir

Fritz Ponsonby, Assistant Private Secretary to King George V, concerning the

succession at Balmoral. (RA PPTO/PP/BAL/MAIN/NS/97 letter dated 27 May 1919

from Sir Dighton Probyn to Sir Fritz Ponsonby).

“But you know from conversations we have had together how highly I have

thought of Michie and really feel for him in the very difficult position he was

put in thanks to that cowardly “stabbing in the back” old devil Donald Stewart,

who did his best to damn him even when he (Donald) knew Michie was the King’s

nomination. Had not His Majesty

authorised me, in fact told me, to speak as I did to Donald and others on

Michie’s first appointment as Factor, they the anonymous writing slanderers,

would have had the poor fellow out of office before he had been many weeks in

it.”

There is one

cryptic entry in John Michie’s diary which may, or may not, be relevant to the

campaign against him. On 19 April 1901,

John Michie “Received a letter from Sir Henry Arnold White, 14 Great

Marlborough Street, London which I do not quite understand”. Sir Henry White, of Arnold and Henry White,

Solicitors, acted for King Edward VII.

All that can be concluded is that the communication was likely from the

new monarch, likely concerned Michie’s employment at Balmoral but was unlikely

to be related to James Forbes’ resignation later that year. This was another frustrating example of John

Michie’s caution in not revealing sensitive issues, even to his own diary.

So, Donald Stewart,

though the ringleader, was not alone in trying to terminate Michie’s tenure at

Balmoral. There were “others”, though

Probyn did not identify them. Also, this

group had committed their views to paper (“writing slanderers”). It is likely they were also to be found in

the ranks of the keepers. Further, the

attempted sabotage took place “even after he (Donald) knew Michie was the

King’s nomination”, which suggests there may have been a campaign against

Michie which went on into the latter half of 1901 and possibly also into 1902

after Michie had assumed office. It is

also interesting that Edward VII had formed his own view of John Michie and

followed Royal convictions, even to the extent of instructing Sir Dighton “to

speak as I did to Donald and others”.

Sir Dighton was honest enough to admit in the same letter that, “Yes,

although I myself might have been – in fact was – in the first instance opposed

to Michie being appointed Factor …”.

John Michie was

nominated as factor at Balmoral because it was Edward VII’s view that he was

the man for the job, despite voices around him holding a different

opinion. King Edward emerged from the

episode with much credit having been put in the position of having to reprimand

the retiring head keeper, a man of great standing at Balmoral, for

disseminating false accusations about a fellow senior servant. It appeared that the respect, even adulation

heaped upon Donald Stewart had gone to his head and convinced him that he held

more sway than was actually the case. One wonders if he ever felt any pangs of guilt

in the subsequent years, during which the Michies did so much for the welfare

of him and his family?

It

remains unclear what was the exact nature of the machinations of Donald Stewart

and his co-conspirators, but it is possible that they managed to have some

influence on the Royal Family and Court even after John Michie’s appointment

and assumption of the role at the start of 1902. The timing of a known series of relevant

events throws up a plausible hypothesis.

John

Michie was frustratingly discrete in his diary entries when discussing personal

matters and items which might be sensitive for his employer. However, it has been speculated earlier that

he left some markers behind, inadvertently indicating the state of his emotions

and the stress to which he was being subjected.

These were the length of diary entries, gaps in diary entries and

cessation of entries before the ends of some years. The shorter the entries, the higher the

frequency of gaps, the greater their length and the earlier the making of

entries were terminated in the year, the higher the emotional disturbance that

John Michie may have been experiencing.

The two years, 1901 and 1902, appear to

have been times of stress for John Michie as projected from the diary

markers. Total entries in 1901 were 169,

compared with 47 in 1902. The very few

entries made in 1902 tended to be short, 17% falling into the “brief” category.

There were several major events in 1901.

Queen Victoria, to whom John Michie was devoted, died, the Balmoral

Commissioner, James Forbes resigned and by the beginning of August, John Michie

had been told he would succeed Forbes.

In September, the King and Queen arrived at Balmoral for the first time

since the start of his reign. Donald

Stewart, no fan of John Michie may not have been in a position to mount a

campaign against him before the public announcement of Michie’s appointment,

since he is likely to have been unaware of the thinking of the monarch and his

Court. Did Donald Stewart and his

acolytes only initiate their subversion of the new factor after Michie’s

appointment but before he assumed office?

Sir Dighton Probyn’s words, “even when he (Donald) knew Michie was the

King’s nomination”, suggest that this may have been the case. If so, it would have been understandable that

Michie would have been feeling stressed in the latter part of 1901. He had to settle in with a new monarch with

different ways and priorities from the late Queen, especially during the King’s

first autumn visit to Balmoral in his reign and John Michie had to plan for his

own accession to the new job. It is

known that at the end of November 1901, Donald Stewart tried to subvert

Michie’s authority over the arrangements for the departure of James

Forbes.

The

following year, 1902, was also eventful with John Michie assuming control at

Balmoral almost from the start of the year and needing to establish his own

authority, especially over some senior servants who appear to have still been

plotting against him. The King’s

coronation, planned for the end of June, had to be postponed due to his

development of acute appendicitis, the placing of the crown finally being

accomplished in early August. This was

quickly followed by the King’s autumn visit to Balmoral and all the planning

that entailed. This year, on the basis of the diary indicators, appears to have

been the most stressful time for the new Balmoral Factor. However, the absence of any diary entries

from much of the year eliminated direct clues as to the nature of the

relationship between Factor and monarch.

Did the campaign of Donald Stewart and his co-conspirators gain some

traction? Stewart certainly achieved his

desired impact with the Prince of Wales, as later revealed by Sir Dighton

Probyn. Did the King also succumb to

Stewart’s tittle-tattle? Was there any

significance in John Michie’s omission from the invitation list to the first

coronation event, when by historical precedent, he would have been expected to

travel down to London for important state occasions?

Nineteen hundred and three appeared to

have been more settled for John Michie, as judged from diary

characteristics. He made 345 entries,

only 5% of which were “brief”. When King

Edward arrived at Balmoral for his Scottish holiday on 14 September, his whole

demeanour towards John Michie seemed to have changed. He congratulated Michie on the execution of

changes in the Castle which the monarch had ordered, he invited John, Helen and

Beatrice Michie to be present at the Royal supper associated with the Ghillies’

Ball, he visited Abergeldie Mains (where the Michies were living at the time)

socially and he rewarded John with the MVO and “expressed himself pleased with

all I have done”. That this represented

a change of behaviour towards him was supported by John Michie’s statement

after being made a Member of the Victorian Order, ““HM’s kindness surprised

me”. (author’s emphasis).

The

year 1903 was also an important one for King Edward, since in August his

representatives managed to persuade the Brown family to sell Baile-na-Coile

back to the monarch. However, it was the

end of June 1904 before the Browns relinquished the keys, presumably in line

with the agreement which had been made.

Interestingly, the King did not retain the house for the use of his many

guests, as he had done with Craig Gowan, though it would have served that

purpose very well. Baile-na-Coile is a

very grand house not far distant from Craig Gowan and nearer to the

Castle. However, it was offered instead

to John Michie as an alternative to Abergeldie Mains, another fine house but a

bit distant from Balmoral Castle as a base for the Estate Factor. Was this another supportive gesture to Michie

for work well done, and possibly as recompense for the negative campaign he had

had to endure? The actual date on which

Michie was told that he would be moving to Baile-na-Coile is not currently known

but it must have been well before the end of June 1904, when the Browns handed

back the keys to the house. During the

first three weeks of July 1904, John Michie was extremely busy arranging for

carpets and furniture. He slept in

Baile-na-Coile for the first time on 22 July.

During King Edward’s annual visit to Deeside starting on the 12th

of the month, a programme of enhancements to Baile-na-Coile was agreed and Sir

Robert Rowand Anderson engaged for the design work. He was one of the most famous Scottish

architects of the time and, as the monarch would discover, not the

cheapest! Was this project, too, a

reward for Michie?

Mains of Abergeldie

There is a

remaining puzzle concerning the appointment of John Michie to the job of

managing the Royal estates on Deeside and that is the choice of job title. Andrew Robertson, Alexander Profeit and James

Forbes were all appointed as “Commissioner”.

John Michie was titled “Factor”, but his successor, Douglas Ramsay, and

Ramsay’s replacement, Douglas Mackenzie, reverted to the original

description. It was made clear to John

Michie from the start that his title wouId change from that of his

predecessor. “Was officially informed by

Sir D.M.Probyn G.C.V.O.&c &c. Keeper of H.M. Privy Purse that the King

had been graciously pleased to appoint me successor to James Forbes Esquire

M.V.O. Commissioner at Balmoral. My title to be Factor instead of

Commissioner”. In practical terms, there

seemed to be no difference in the managerial role being fulfilled but it was

implied by Sir Dighton Probyn that there was some difference in status adhering

to the two appellations, in two separate documents. “Note to James Forbes. Sir DP to communicate with Messrs Martin and (indecipherable)

WS to prepare a document or mandate appointing Mr John Michie as Factor at

Balmoral not Factor and Commissioner”. (RA PPTO/PP/BAL/MAIN/OS/838 note dated

22 Oct 1901 from Sir Dighton Probyn to James Forbes). “Michie’s successor, who I am glad to see, he

being the Sovereign’s servant, is to be called “Commissioner” and not “Factor””.

(RA PPTO/PP/BAL/MAIN/NS/97 letter dated 27 May 1919 from Sir Dighton Probyn to

Sir Fritz Ponsonby). Almost all other

estates with which John Michie had dealings were managed by Factors. One exception was William McIntosh, Factor

and Commissioner on the Fife estates in 1912.

Even in this instance, the title varied from time to time. The puzzle remains, but was the implication

of the title “Factor” that it was a step down in status from the

alternative? If so, was this change an

attempt by the King to appease those at Court who thought that Michie was not

the ideal candidate for the role?

The family

of John and Helen Michie

In part 1 of

this biography of John Michie, which roughly covered his life up to 1902, the

educational history of the Michie children was explored. Here, the subsequent careers of the family

members and some other close relatives are presented, since these details are

important in understanding John Michie senior’s period of office as the

Balmoral factor.

Annie Michie

(1879 – 1958)

At the time of

the 1901 Census of Scotland, Annie Michie, then aged 21, was still living at

home, perhaps acting as mother’s help in a busy household. But just a few months later, in August, at

the time of the announcement that her father would be the next factor on the

Balmoral estates, Annie appeared to have been working at the Fife Arms hotel in

Braemar. In November 1901 she departed

for a position in France, though its nature has not been uncovered. Annie returned from the Continent three years

later, about November 1904, stopping to see friends and relatives in Kent and

Glasgow on her way north.

The next

employment of the Michies’ eldest daughter was as housekeeper to “Mr & Mrs

Pirrie of Harland & Wolff”, the Belfast shipbuilder, Annie taking up the

role in March 1905. William Pirrie was

an important figure in British national life.

He was chairman of the company between 1895 and 1924 and held the post

of Lord Mayor of Belfast in the period 1896 – 1898. Probably the most famous ship constructed at

the Harland and Wolff yard was the Titanic, completed in 1912. Pirrie had made a number of public statements

about the vessel being unsinkable, which tragically proved to be

inaccurate. Annie Michie only remained

in post for about 11 months for in February the following year she was

appointed housekeeper at Sandringham House, the Royal family’s residence in

north Norfolk. She must have parted with

the Pirries on good terms because in August 1906 the Pirries were staying at

the Fife Arms hotel, Braemar, and invited John and Helen Michie to meet them

there for tea. John and his wife were

accompanied by his brother David and his daughter, “Ceylon” Annie. In September of the following year Lord and

Lady Pirrie, accompanied by Lord and Lady Bathhurst (a newspaper owner) called

on the Michies at Baile-na-Coile. This

social call was followed by an invitation for lunch to Helen and Annie Michie

with Lady Pirrie. It is to be wondered

if Annie originally made the acquaintance of the Pirries while she was working

at the Fife Arms.

Viscount Pirrie, Chairman of Harland and Wolff

Annie Michie

would remain as Sandringham housekeeper for the rest of her working life. She would often return to Balmoral in the

autumn for an extended holiday, that being a time when Sandringham was not in

Royal occupation. When Annie Michie

first arrived at the Sandringham estate, the land agent there was Frank Beck,

who had succeeded his father, Edmund, in this role in 1891. Annie became good friends with Frank Beck’s wife,

Mary, and John Michie would sleep at the Beck’s house when he visited the Royal

estate in Norfolk. (Frank Beck would

later be the moving force in the formation of the Sandringham Volunteers, which

he led during the Gallipoli campaign in 1915.

Frank and many of his colleagues were killed in action at Suvla

Bay. John Michie got the news on 25

August. “Saw Sir Frederick (Ponsonby)

when told me a telegram had come to Mr Beck, Sandringham, been missing at the

Dardanelles since the 12th August!!

Very sorry at this sad news”. In

1915, Sir Dighton Probyn had presented Frank Beck with an engraved wristwatch,

which was with him when he died. After

the War, this timepiece was found in the possession of a Turkish officer,

bought from him and returned to the Beck family).

Until 6 April 1915, Annie Michie

had remained single but then she married widower J Walter Jones, a local

schoolmaster at West Newton in the Parish of Sandringham, which was on the Royal

estate. Annie was 36 and Walter rather

older at 58 years. Walter Jones was

first mentioned in John Michie’s diary in September 1911, when the schoolmaster

accompanied the Royal party to Balmoral, though it is unclear if a friendship

with Annie Michie had been ignited by this date. Although the marriage took

place during WW1, many of the Michie family managed to make the journey to

Norfolk from various parts of the country.

John and Helen Michie started by train from Aberdeen and met their son,

Henry in Newcastle, joining up with brothers David and Jack in

Peterborough. John Michie noted, “The journey without incident other than

a big fleet of war craft in the Forth and soldiers travelling by rail in large

numbers, in fact "Khaki" in evidence everywhere”. From Peterborough, the Michies travelled on

to Kings Lynn by rail where the group was supplemented by son Victor, his wife

Georgie and Annie Kitchin, a cousin who lived at Tonbridge in Kent.

Although Walter Jones had no

formal role on the Sandringham estate he was well connected there. Walter was particularly close to the two

oldest boys of King Edward VII, Princes Albert and George. Their regular tutor was Henry Hansell, a

former master at Eton College, who taught various Royal children between 1902

and 1915. When Hansell went on holiday,

Walter Jones would step in as his unofficial understudy. Walter, a skilled naturalist, often used to

conduct the Royal princes on nature walks through the parks, woodlands and

marshes around the Sandringham estate.

Jones also organised occasional football matches involving the princes

and lads from the local school, when no quarter was given to the Royal

participants.

Walter Jones also took on another

honorary role at Sandringham, that of looking after the Royal racing pigeon

loft. Pigeon racing is generally looked

upon as a proletarian activity. It is

not a sport of great antiquity, the first regular pigeon race in Great Britain

being initiated as recently as 1881.

Royal involvement in this obsession of the working man began in 1886

when Prince Albert of Wales received a gift of racing pigeons from King Leopold

II of Belgium, and his father Prince Albert Edward of Wales arranged for a loft

to be constructed to house the new Sandringham residents. The breeding program at the Royal loft was

successful and in 1899, the Prince of Wales’ bird won the National Flying

Club’s Grand National. From 1893, the

Royal racing pigeons competed under the name of Walter Jones.

Walter died at Sandringham aged

80 in 1938. He had been headmaster at

West Newton for 40 years. In her

widowhood, Annie retired to Edinburgh, surviving her husband by 20 years. However, her remains were returned to

Sandringham for burial.

David Kinloch Michie (1881 –

1949)

The second

child, but oldest son, of John and Helen Michie and the first to be born on

Upper Deeside was baptised with the given names “David” and “Kinloch” in honour

of his paternal grandfather. By 1901 he

had begun work in the factor’s office on the Durris estate, Kincardineshire,

which lay between Aberdeen and Stonehaven.

Durris House, the principal residence on the estate, was built, or

rebuilt in the 16th century, though subsequently much modified. By 1901, this estate was in the hands of the

Baird family, who had made a fortune from their industrial interests in the

West of Scotland, principally the Gartsherrie Iron Works. When DK Michie started his employment at

Durris, the Laird was 30-year-old Henry Robert Baird, an enlightened owner who

did much to improve the living conditions of the Durris tenants and

servants. The “estate agent and factor”

on the Durris estate during David Michie’s time there was Thomas Braid, who had

been born in Fife in 1851. Before

arriving at Durris, Thomas had worked as sub-factor to Lord Lovat at

Beauly. Durris was a good starting

position for aspiring estate manager, David Kinloch Michie.

Durris House

Henry Baird was

a keen supporter of the Volunteers and his new assistant in the estate office

at Durris sat his examinations in Aberdeen at the end of March 1901, for the

rank of captain, though initially he would only hold the actual rank of second

lieutenant in the Durris Company of the 5th Volunteer Battalion of

the Gordon Highlanders. David Michie was

soon embedded in the social life of the community around Durris, though he

would occasionally return home to Balmoral at weekends. At the end of July, the Durris Company of the

Volunteers held its annual picnic and games in a field near Kirkton of

Durris. DK Michie was a prominent

competitor, being placed third in throwing the hammer, third in putting the

ball, 4th in the caber, 3rd in the hop, step and leap and

2= in the high leap.

David Michie

attained his majority on 27 February 1902 and his father, as was traditional,

sent him his birth-certificate. The

Michies’ eldest son was promoted that year to the rank of Lieutenant in the

Durris company of Volunteers and he also competed at the Aberdeen

Wapinschaw. David did not resign his

commission until 1906, long after he had left the North-East of Scotland. However, David and possibly his father, were

keen for the first son to broaden his managerial experience. In February 1903, after attending meetings in

Aberdeen, Michie senior “Came out to Durris last night and spent it with Mr

& Mrs Braid to discuss David's leaving there for some other

experience”. He resigned his position in

the Durris office from early March. The

parting was amicable and David occasionally paid return visits to Durris. When Thomas Braid died in 1908, David Michie

travelled from the West of Scotland to be present at his funeral.

David gained a

new position in the office of the extensive Elderslie estates, located in

Renfrew. These estates were owned by Mr

Archibald Alexander Speirs who had inherited them, through his father, from his

grandfather, Alexander Speirs. The lands

included the Barony of Houston, the Fullwood estate and the lands of

Blackburn. Alexander had made his

fortune as one of the Glasgow Tobacco Lords.

These Glasgow merchants, who became fabulously wealthy, made their money

out of the triangular trade, exporting textiles, rum and manufactured goods from

Britain to Africa, slaves to the Americas and sugar, tobacco and cotton back to

Europe. At his death in 1782, Alexander

Speirs was claimed to have assets valued at £153,000. The Elderslie estate had at one time belonged

to Sir Malcolm Wallace, father of William Wallace, the Scottish patriot, and

Alexander Speirs is thought to have owned two double-handed swords previously

the property of Wallace. The Speirs

family crest was derived from William Wallace’s crest, but with the sword

replaced by a spear. James Alexander

Ferguson was the estate factor at Elderslie when David Michie arrived in 1903

as his senior assistant. Ferguson was

appointed in 1896 and had previously worked as the architect on the Glamis

estate.

Elderslie House

David Michie

often took his holidays from his job in Renfrewshire back on Deeside, where he

enjoyed the sporting facilities on offer.

He must have been getting along well with his immediate boss, James

Ferguson, because in September 1904, Ferguson and his wife, who had been on

holiday in Strathpeffer, motored over to Balmoral and spent “a night or two”

with the Michies.

In 1906, James

Ferguson resigned as factor on the Elderslie estate due to declining health,

dying two years later, and David Kinloch Michie was appointed in his

place. This was a remarkably rapid

promotion for Michie, who was 25 at the time and had only accumulated five

years’ experience of factorial work. He

must have impressed his employer, Mr Speirs, and likely the predecessor factor

too. David’s parents were no doubt

chuffed to receive the news. “Telegram

received from David Kinloch, our eldest boy that he had just been appointed

Factor at Elderslie”, was the modest entry in John Michie’s diary for 4 August

1906. Michie senior paid his first visit

to Elderslie in November 1906. “Spent

today with David at Elderslie. We went

to Paisley, Elderslie Village & Johnstone in the forenoon. Afternoon went to Houston”, though the West

of Scotland weather was unhelpfully “droppy”.

The same year, David gave his father a new rifle, which, on first use,

did not perform perfectly. “Went to the

deer on Craig Darign in very deep snow high up but had little luck. I tried the new rifle David gave me. It snapped at a hind but went off second try

& I got a hind, neither Smith (factor at Haddo House – see below) or

David had any luck”.

In December

1906, John Michie set out for London in order to attend the Smithfield fat

cattle show, taking in the similar show in Edinburgh on the way. There he met up with his son David, now

promoted to the ranks of the estate factors and the pair attended the Factors’

Meeting and dinner at the Carlton Hotel before they departed for their separate

destinations. With his new

responsibilities, David started to innovate at Elderslie, consulting with his

father about the practicalities of installing acetylene lighting in Neilson

House, since Michie senior had used this system of illumination both in Baile-na-Coile

and The Croft.

The M’Hardys of

Braemar were a family of big men.

William (1804 – 1867) was Head Keeper on the Mar Estate for many years

and performed competently in the heavy events at the Braemar Gathering. He had a family of eight legitimate

offspring, plus a couple who were “natural born”. Three of his sons became prominent

policemen. William (1836 – 1906) joined

the Aberdeenshire force and reached the rank of inspector, Alistair (1838 –

1911) became Chief Constable of Sutherlandshire and retired as head of the

Inverness-shire force and Charles (1844 – 1914) became the Chief Constable of

Dumbartonshire. Although these M’Hardy

coppers had departed Braemar before the arrival of John Michie on Deeside in

1880, they were known to him.

Charles

M’Hardy, as chief constable of Dunbartonshire, was responsible for policing the

launch of the ocean liner “Lusitania” from the Clydebank Shipyard and he

invited John and Helen Michie to attend the celebrations around the event. This was an ideal opportunity for the Michies

to fulfil both the invitation and to visit Elderslie at the same time. The Lusitania was launched on 7 June 1907,

which was also the day that the Michies travelled down to Glasgow. The following day John and Helen “Went over

the "Lusitania" the biggest ship afloat at the present time. Went up Loch Lomond in afternoon and got

rain”. (The Lusitania was subsequently torpedoed

and sunk by a German U-boat off the south coast of Ireland on 7 May 1915. There was a loss of about 1260 lives,

including many Americans, which event is thought to have been influential in

bringing the USA into WW1).

After his

removal to the West of Scotland, David Michie became very active in athletic

and sporting activities. During the

summer of 1905 he was involved in several 100 yd and 200 yd handicapped running

races and from 1907 he entered Highland games, mostly in the heavy events, such

as putting the shot and throwing the hammer.

In 1911 he was a competitor at the Braemar Gathering. David also became a member of the National

Rifle Club of Scotland and played cricket regularly for Renfrew, where he was

appointed assistant captain in 1909 and captain the following year, a position

he held until the start of WW1. In the

1912 season DK Michie took 81 wickets, being first equal in the Glasgow

area. David Michie represented the

National Rifle Club of Scotland at Bisley in 1910. The following year he was present at Bisley

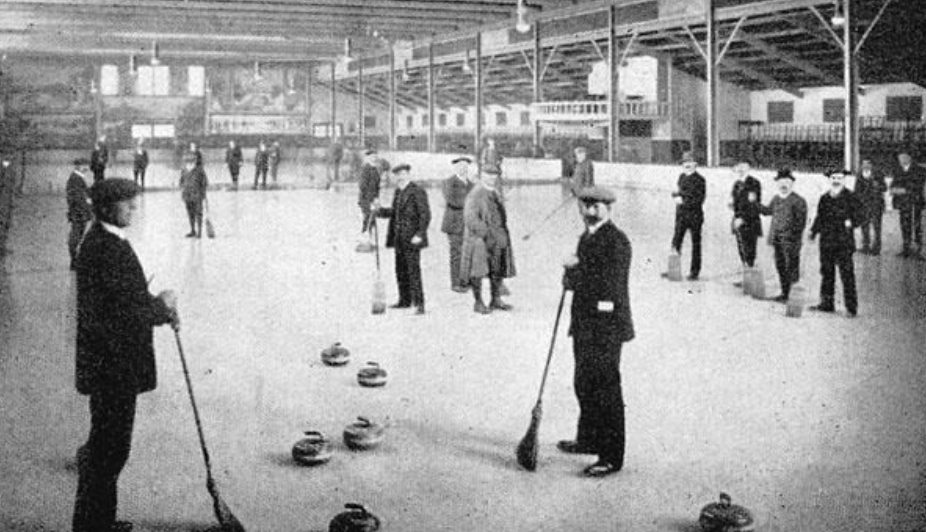

again and “found a place on the prize list even though he was a tyro”. Inevitably, given his upbringing on Deeside,

David Michie was also a keen participant at shooting, fishing and curling. In this latter sport he played for the

Renfrew King’s Inch club.

David Kinloch

Michie married Jean Walker in summer 1912.

He was 31 and his wife was 5 years his junior. Jean was the daughter of school headmaster,

Archibald Walker from Yoker, Dumbartonshire and Jean was herself an assistant teacher. The couple appear to have had only two

children, John born before December 1915 and Jean, born in 1919 after David

Michie’s return from war service.

Shortly after

the start of WW1, David Michie joined the Army and was soon promoted to be a

temporary captain in the 1st Glasgow Battalion of the Highland Light

Infantry. He was posted to Gailes Camp,

near Irvine in Ayrshire, presumably for officer training, which lasted for 4 ½

months. David was still at Gailes Camp

the following May but due to be moved out to Kendal. David Michie managed to get two days’ leave

at the start of 1915, when he travelled back to Deeside and took part in the

New Year shooting competitions traditionally held on the Balmoral estate on 1

January. He was first with a score of 23

out of a possible 25 and thus gaining a small gold medal donated by King George

V. The following day, in the company of

brother Victor, David went to the hill after hinds. He killed five out of a total bag of nine.

About 11 May,

David Michie was posted with his regiment to Prees Heath Camp in North

Shropshire but was able to get a few days leave and travelled with his wife

back to Deeside, before having to return to his regiment for the next move to

Salisbury Plain at the start of September 1915, where serious training in

simulated war conditions took place. A

few days after arrival, David was “… wounded in the leg by a splinter from a

bomb while observing practice …”. He was

sent home to Renfrew to recuperate and was well enough to travel to Deeside to

see his parents. John Michie found him

“… yet very lame from his bomb wound …”.

In February 1916, David Michie was promoted to the rank of temporary

captain from 9 February, but with seniority backdated to 1 September 1914. He was first posted to France in 1916. In December of the same year, David was

promoted again, this time to temporary major in the Highland Light

Infantry. David Michie was mentioned in

dispatches and was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order in January

1918. He was still serving in France in

mid-October of that year and did not arrive home from the continent until 20

February 1919, on which date he relinquished his command. DK Michie then resumed his position as factor

on the Elderslie estate of WAA Hagart-Spiers, though he soon found time to

visit Deeside.

With the war

over, it was time for David Michie to reconnect with the various strands of his

civilian life. He had had a good war,

his status in the Renfrew community was now substantial and local politics

appeared to beckon. In the School Board

elections for Renfrewshire, held in April 1919, there were 74 candidates for 35

seats. Major DK Michie was successful in

the Upper Renfrewshire Division. At the

Scottish National Milk and Health Association Preliminary meeting held in

Glasgow in November 1924, Major DK Michie was present as the representative of

the Association of Education Authorities in Scotland. By 1927, David Kinloch Michie was a local

councillor in Renfrew and in the municipal elections of that year he was again

a candidate in Ward 3. He sailed under

the label of “Mod” (Moderate?) and was opposed by a Labour candidate. David Michie was elected again. There were many Labour candidates in the

West of Scotland in these elections, plus an occasional Communist or

Socialist. This was a time of

substantial unemployment and significant social unrest in the aftermath of

WW1.

After the war,

David was soon back on the cricket green, playing for Renfrew against other

Scottish counties. He also resumed the

captaincy of the team. By 1922, David

had also returned to competitive rifle shooting at Bisley, as a member of the

Scottish team contesting the Elcho shield.

In 1925 and

1926 there was a major sale of land by the Elderslie estate, which was fronted

by David Michie. This disposal included “West

Forth farm and croft; Eaglesham estates for sale including the Mansion house

and policies”, consisting of 9886 acres, with an upset price of £147,000 and “Fingalton

agricultural estate”, with an upset price of £17,330.

The Secretary

of State for Scotland established a committee on allotments in Scotland in

1931, presumably with the intention of helping the working class to feed

themselves cheaply and Major Michie was invited to serve on this body. In 1932, David Michie, who by this year had

become Provost of Renfrew, opened an unemployed men’s social club in a shop in

Fulbar Street, which had been fitted out by the beneficiaries. In his role as Provost, David Michie took a

leading role in community initiatives, such as raising money for the relief of

suffering resulting from the Gresford Colliery disaster, near Wrexham, when an

underground fire resulted in the deaths of 266 men.

But Major

Michie (he continued to use his Army rank in civilian life), perhaps influenced

by his no-nonsense, military background, could at times behave in an authoritarian,

even autocratic fashion, a charge which had previously been laid at his

father’s door too. Renfrew had an

airport which started life as a military airfield during WW1 but became a

civilian facility subsequently. The

first scheduled flights from Renfrew, serving Campbelltown on the Mull of

Kintyre, started in 1933. Sir Alan

Cobham had been a military aviator in WW1 and subsequently was involved in a

variety of aviation businesses and pioneering flights. In 1929 he initiated his Municipal Aerodrome

Campaign to encourage town councils to build airport facilities, by touring the

country giving free flights to dignitaries and paid flights to the general

public. From 1932 he ran National

Aviation Day displays at many venues around Britain. These displays were very popular. In planning for a further program of events

in early 1935, Cobham wrote to Renfrew Town Council asking for permission to

mount an air display at Renfrew Airport in the following July. Provost Michie was unimpressed, giving the

view that “Renfrew had had sufficient air displays”. The councillors fell in behind their leader

and permission was refused.

The rejection

of Sir Alan Cobham was as nothing compared with the Renfrew Provost’s next spat,

this time with a national authority. In

April 1938 he took the dramatic decision to shut down Renfrew Airport with only

two weeks’ notice. The affair was

reported in the Aberdeen Journal. “This

dramatic announcement was made by Major DK Michie Provost of Renfrew during a

civic luncheon yesterday the purpose of which was to celebrate the new Glasgow

– Perth – Inverness air service. Renfrew

had been due to operate 26 air services in the coming season. Michie said that the unanimous decision of

the Renfrew Council was due to the “procrastination and discourtesy by the

Civil Aviation Department of the Air Ministry.”

The Council have spent about £11,000 on airport improvements as well as

sustaining £300 to £500 annual loss, since taking over the property. “We are most anxious to have an airport in

Renfrew” said Provost Michie “and to encourage civil aviation but at a

price. It is all wrong for a

municipality to subsidise what ought to be a national service. Reasonable ratepayers will not allow this

state of affairs to continue”. “Guarantees had been sought from the Air

Ministry that if certain extensions were carried out Renfrew Airport should

remain as the recognised civil airport for the south-west of Scotland during

the next two years”. Michie’s

announcement was a bombshell and caused quite a fuss. A telegram was quickly dispatched from the

Air Ministry in London giving a guarantee for the next two years but

emphasising that it could not be given for longer because of the limitations at

Renfrew relating to its further development.

In truth, a replacement site was needed, and a new airport was

subsequently developed at Abbotsinch east of Renfrew and remains as Glasgow

Airport today.

David Kinloch

Michie played a prominent role in the civil defence of Renfrew and the

surrounding area during WW2. In early

1939 with the prospect of war looming, he was appointed ARP (Air Raid

Precautions) Controller for the county of Renfrew. In this role he was responsible for the

organisation of support services needed should there be a bombing raid on the

town, such as enforcement of blackout regulations, recruitment of ambulance

drivers, organisation of rescue parties and liaison with police and fire

services. One decisive action that he

took concerned a Council employee in the Roads Department, who refused to

undertake decontamination training but, intolerably in the eyes of the provost,

actively canvassed his colleagues to decline instruction too. The provost moved a motion in council for the

man’s dismissal, which was passed by 21 votes to five. Michie then had a spat with the Home Office

over the costs of providing a warden service.

In 1940 he caused notices of suspension to be sent to 122 full-time paid

ARP workers but with an agreement to meet on the apportionment of costs, the

suspensions were lifted. This was the DK

Michie way of getting things done.

In 1942, David

Michie resigned as Provost of Renfrew, for “health and business reasons”. This was the start of his retreat from public

life. He suffered from bowel cancer and

heart disease and died in 1949. Other

than his war service when he received the DSO and was mentioned in dispatches,

he was a Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Renfrew, Lord Provost of Renfrew

between 1930 and 1942, a member of the Town Council for 25 years and of the

County Council for 32 years and a member of the County Education Committee for

ten years, including six years as its chairman.

In 1943 he was awarded the OBE for his work as the Renfrew ARP

Controller. David Kinloch Michie had led

an interesting, productive and prominent life.

Victor

Michie (1882 – 1952)

The latter years of Victor

Michie’s schooling and his early adult life remain obscure due to the absence

of John Michie’s diaries for 1898 – 1900 but it is known that at the Braemar

picnic (not the Braemar Gathering) held in July 1898, Victor won the boys under

15 race and three years later, he was again a competitor in the sports, coming

first and second in the golf driving competition. As early as 1901, Victor, then aged 17 years

attended a meeting where it was proposed to establish a corps of mounted

infantry in association with the Gordon Highlanders. Victor signified his intention to join the

proposed corps.

By early 1901 Victor was working

as an assistant seedsman at the nursery of Ben Reid & Co in Aberdeen. Victor lodged in Aberdeen but often came home

to Balmoral at the weekends. It is

likely that Victor secured this position through the good relationship that his

father had with the principals of the Ben Reid company. However, in May 1901, Victor’s father noted “Saw Victor who has again been troubled

with his eyes” and these sight problems forced

the lad to give up his work with Ben Reid & Co.

By 1903, Victor’s vision had

improved sufficiently for him to undertake a new job at Walhampton, near

Lymington in the New Forest. Victor’s

father, on a visit to the Smithfield Show in December 1903, extended his

journey to travel down to Lymington. “Arrived in London this morning &

proceeded to Walhampton, Lymington, Hampshire to see

Victor, who is well & in good spirits. He introduced me to Major his

master. Put up at the Hotel for the

night”. Thereafter, occasional reports

of Victor’s whereabouts indicated that he was still working at Walhampton. On 10 April 1904 he appeared to suffer an

accident when riding into the mews of the Angel hotel, Lymington, when his

horse fell, pitching him to the ground.

He was shaken but not seriously hurt.

The following December he travelled home to Deeside on holiday and in

January 1905 he danced a Highland fling at a Burns supper organised by the New

Forest Caledonian Society and held in the Town Hall, Lymington. Everything seemed to be in order in Victor’s

work and social environment.

However, an

alarming, but cryptic, diary entry by John Michie on 27 April 1905 suggested

that all was not well in son Victor’s world.

“Heard awkward news of Victor from John Kitchin. … Received harassing

news from Lymington Dr Maidstone rather”. (John Kitchen was a brother of Helen Michie

who farmed in Kent. “Dr Maidstone”

probably refers to a medical doctor in Maidstone, Kent.) The same day as John Michie’s anxious diary

entry, Victor received a leaving present at a gathering in the Angel Hotel,

Lymington. The event was recorded in the

Western Gazette. “Presentation at Angel

Hotel, Lymington to Mr Victor Michie who is leaving. “Mr CW Orman occupied the chair and Mr HC

Heppenstall the vice-chair. At the close

of an excellent repast served in Host Walter’s best style, the Chairman

presented to Mr Michie on behalf of his numerous friends a handsome travelling

dressing case and a silver cigarette case expressing a few appropriate words of

regret at his departure from Lymington and of good wishes for his future. Mr JA Coughlan gave expression to similar

sentiments and Mr Michie suitably acknowledged the good wishes and the handsome

gifts. The remainder of the evening was

convivially spent”. (HC Heppenstall

was a solicitor in Lymington and “Major” and “Mr CW Orman” may have been Major

Charles Orman, soldier and cricketer).

One possible

explanation for this sketchy series of events was that Victor suffered an

injury or illness, possibly a recurrence of his previous eye problem, and

retreated to his uncle’s house in Kent to seek medical help and family support

and that the problem was so severe that there was no prospect of him continuing

in his job at Lymington. However, it

seems more likely that the true reason for Victor leaving his job at Walhampton

was that he had planned to emigrate to Canada and had sprung the news on his

family at the last minute, perhaps knowing that they would disapprove and try

to persuade him to change his mind.

Perhaps he visited his uncle in Kent to use him as a conduit of

information back to Scotland? Victor

departed from Liverpool on 4 May 1905 for Quebec, sailing on the “Kensington”

of the Dominion Line. He does not appear

to have visited Deeside before his departure from Britain.

Why did Victor

choose Canada as an emigration destination?

He may have been influenced by his younger brother Henry Maurice, who,

in 1900, had won a bronze medal in a competition promoted by the Canadian

Government to improve knowledge of the Dominion and thus to encourage

emigration there (see below).

After 27 April

1905, there was no further reference to Victor in John Michie’s diaries until

23 December 1911, when John noted, “Received a telegram at 8 o'clock from

Victor saying he and his wife had arrived in Liverpool last night - that they

would be at Ballater at 5 o'clock, which they were”. This absence of any reference to Victor was

despite diaries being available for 1905, 1906, 1907 and 1909. Did this omission indicate a level of family

disapproval for Victor’s actions? Victor

had married Georgina Myrtle Anderson at Strongfield, a very small settlement in

Saskatchewan in November 1910. It

appears that the visit by Victor and Georgina to Deeside at Christmas 1911 may

have been the result of a reconciliation between Victor and his family, after

his surprise departure six and a half years previously. “Walked as far as Boat pool with Victor &

Jack. Mrs. M., Alix. &

"Georgie" Victor's wife attended Xmas service”, was part of John

Michie’s diary entry for Christmas Day.

Brother David Kinloch arrived from Renfrew on 28 December and stayed

over the New Year period. Victor enjoyed

both grouse and roe hind shooting during his Balmoral sojourn.

Early in

February 1912, Victor and Georgie departed from Liverpool on the “Empress of

Ireland”, arriving at St John, New Brunswick on the 17th of the

month. Victor was categorised as a

returning Canadian and was destined for Winnipeg, Manitoba. Two years later Victor and his wife were

living in a different province, at Shaunavon, Saskatchewan. But their next visit to Britain’s shores had

an altogether more sombre purpose. In

August 1914, shortly after the start of WW1, Victor enlisted with the 5th

Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force at Valcartier but about a month

later he transferred to the Imperial Forces overseas. Victor and his wife travelled from Montreal

to Liverpool on the “Missanabie” of the Canadian Pacific Line. He was described as a civil engineer and his

destination address was Baile-na-Coile, the home of his parents on the Balmoral

estate.

Christmas 1914

must have been a time of anxiety and anticipation in the Michie household but

with two sons at home, Victor and David, the worries of what was to come could

be put aside for a few days while the traditional shooting competitions and the

pursuit of game were indulged by the estate residents. On 2 January 1915, John Michie noted, “Victor

has been appointed for the 2nd Scottish Horse, but has not yet received his

marching orders”, so the fun continued for a while, the temperature being low

enough for the curling passion of the Michie males to be indulged. In a match skipped by John and Victor on 6

January, Michie senior won 17 : 3 but a few days later Victor gained revenge,

winning 10 : 6. A final fling at the

“roaring game” occurred on 28 January, which ended equal. The following day, Victor left Deeside for

Chester-le-Street to join his unit.

With all four

Michie sons (David, Victor, Jack and Henry) away with their units, the women at

Baile-na-Coile were free to travel. In

mid-February 1915, Georgie Michie departed for Newcastle on her way to

Sandringham, where she was to stay with Annie Michie, though she hoped to break

her journey to visit Victor at Chester-le-Street. Annie was due to marry Walter Jones, the

local school headmaster, on 6 April. It

was a first marriage for Annie at the age of 36 but a second marriage for

Walter, whose first wife had died.

Following the wedding, Georgie, Alix Michie, with John and Helen Michie

spent some time at Chapel Rossan Bay, Dumfries and Galloway, where son Henry

had been appointed as factor shortly before the start of the war and where

daughter Alix (Alexandrina) was also employed.

The following month, Georgie also visited Gosforth Park, Northumberland,

where Victor was then stationed.

By Friday 13

August 1915, Victor had received orders to depart for Egypt the following

Monday. Georgie quickly departed from

Deeside for Morpeth, Northumberland to see her husband before he embarked for

the East. Henry Michie was also sent to

Egypt. From that country the two Michie

brothers were moved to Turkey and the Gallipoli Campaign. In late September two postcards arrived at

Baile-na-Coile from Henry Michie, one dated 4th of the month,

reporting that he and Victor were both “in trenches but well”. However, it did

not take long for Victor to catch, and be hospitalised at Mudras, by an attack

of dysentery. Further news was

sporadic. At some stage that autumn

Victor received a wound and was moved to the Greek island of Lemnos. He was also promoted, firstly to the rank of

Lieutenant and then to captain in the 27th Light Horse. He was placed on reserve on 23 September

1916, due to medical unfitness. Victor

returned to Canada on 17 March 1917, where he was employed in the headquarters

of Military District 12 in Ottawa. He

was further promoted to the rank of captain in July of the same year. Victor remained in this post until his

resignation on 31 March 1918 and was discharged at Regina.

By September

1919, Victor and Georgie were residing at Loreburn, Saskatchewan. After his return to civilian life, Victor

Michie was engaged in a long and confusing correspondence with the military

authorities regarding gratuities due to him.

The problems arose from his sequential service, first with the Canadian

military, then the Imperial Forces and finally with the Canadians again. It was difficult for the authorities to

establish the details of his mixed military career and thus to be in a position

to calculate his entitlements. This

confusing episode was not finally resolved until mid-1920.

At the 1921

Census of Canada, which was taken on 1 June, Victor Michie was boarding with

Alexander Cameron a farmer born about 1853 in Scotland, who was living at Mill

Road, Boissevain, Manitoba. Victor who

was 39 years old and married, was described as a “Cont Engineer” (contracting

engineer?). He had Canadian nationality,

was a Presbyterian and could speak both English and French. It is likely that by this year Victor was

involved in the extension of the rail network in Western Canada, where he is

known to have worked for both Canadian National Railways and Canadian Pacific

Railways.

According to

the recollections of John Michie’s descendants, after Victor came home from the

war he found a new love, Nellie Sadie Smith, left Georgie, his first wife and

eventually, in 1928, married Sadie. At

the time of his second marriage, Victor was 46 and his new bride was 35. The reaction to this turn of events in the

staunchly Presbyterian Michie family back in Scotland was one of both shock and

disgust. Expressions of this revulsion

included the obliteration Victor’s image in group photographs of the family and

the severance of communication with him.

Despite the negative feelings of the British-based Michie family

members, the Aberdeen Press and Journal carried a report in 1946 of a new

appointment for Victor. “Major Victor

Michie a native of Aberdeen has been appointed surplus property engineer of War

Assets Corporation, Canada. Major Michie

takes charge of a new division responsible for the acceptance of surplus lands

and buildings and their custody and maintenance pending their clearance or

disposal. He has been with the

corporation for some time as chief of the construction and engineering division”. Victor died in 1952 and was buried in Elmwood

Cemetery, Winnipeg.

Henry

Maurice Michie (1885 – 1949)

Harry Michie

was the fifth child and third son of John and Helen Michie. In September 1901 Henry Maurice started

attending Aberdeen Grammar School but did not subsequently go on to university. He was not comfortable living away from home

and often returned there at weekends.

However, he was clearly a bright boy, as shown by his performance the

previous year in a competition promoted by Lord Strathcona on behalf of the

Canadian Government. Lord Strathcona had

been born in Scotland but had emigrated to Canada where he was highly

successful in business and national life.

Schools were invited to receive textbooks and atlases for the study of

Canadian geography and resources and then for individual pupils to take part in

an examination of their acquired knowledge of this vast dominion in North

America. Crathie School was a

participating institution and Henry Maurice Michie entered as a candidate in

the examination. He came first and was

rewarded with a bronze medal, which bore the inscriptions, “School Competition

1900 subject “The Dominion of Canada” and “presented by the Canadian Government

1900””. The aim of the Canadian

Government, which appeared to have been successful, was to make the younger

generation more familiar with the resources of Canada and thus more likely to

emigrate there. At a meeting of the

Crathie and Braemar School Board held on 19 March 1901, “Medal won by Henry

Maurice was shown to S.B. and an entry made in the minute expressing the

Board's pleasure”.

Lord Strathcona

Henry Michie

left Aberdeen Grammar School in 1903 and embarked on a career in estate

management in emulation of his father and brother David. In his diary entry for 12 November, John

Michie wrote, “Maurice left for Strichen Estate Office to begin his career as A

Factor!!”, by which he really meant that Henry Maurice had been enrolled as an

assistant to John Sleigh, the 77-year-old factor on the Strichen, Auchmedden

and Fedderate Estates, though given Sleigh’s age, Henry may have had

aspirations to an early promotion. These

properties, which included Strichen House, had been acquired in 1850 by William

Baird, who made his fortune from iron and steel production in Coatbridge.

In late January

1904, John Michie visited the Strichen Estate “to see how Henry Maurice was

getting on”. He found his son to be

thriving in the estate environment. “Mr.

& Mrs. Sleigh were all kindness and approved of Henry who went to Mr.

Sleigh, Factor to learn estate work on the 12th November last. He seems to like his work and the

place”. During August, Henry returned to

Deeside for a holiday and while he was at home a friend from Strichen, Mr.

Wilson senior clerk in the estate office, paid a visit to Baile-na-Coile. Unfortunately, this happy state of affairs

did not last for Henry Maurice, as a message to his parents in mid-November

showed. “Got a letter from Henry to say

that he has now been laid up with rheumatic fever for about a fortnight &

is getting worse”.

John Michie,

ever the concerned parent, immediately took a train to Strichen to assess the

situation. “Went out to Strichen this (Friday)

morning to see Henry whom I found looking very ill. He had a bad turn yesterday & his

temperature was 103º this morning. We

have made up our minds to make arrangements for getting him home in the

beginning of the week if he is well enough to stand the journey provided the

Dr. gives permission”. The following

Wednesday, the plan was put into action.

“Went from Aberdeen to Strichen by first train where I found Henry

better than he was on Friday & ready to undertake the journey. We had him taken from his lodgings to the

station in a carriage where he was put to bed in a saloon carriage attached to

the 9.50 train from Strichen. On arrival

at Aberdeen, we had some lunch handed in to the carriage & the saloon shunted

on to the 12.20 Deeside train. On

arrival at Ballater there was a closed carriage waiting into which he was

placed & arrived home without mishap about 3.15. Henry was exhausted with the fatigue but the

Dr. who saw him soon after his arrival seemed to think that the journey really

hadn't done him harm”. By the end of

March 1906 Henry’s health was returning to normal and by the middle of May he

had returned to his position on the Strichen Estate, though his father noted,

“He is fairly well but I confess not looking so robust as I would like

him”. Ann Sleigh, the Strichen factor’s

wife, became friends with Helen Michie and started to make occasional visits to

Balmoral, the first of which was in October 1907. “Later drove to

Ballater with Mrs Michie in pouring rain. Met Mrs Sleigh off 2 pm train. We all had tea in the Invercauld Hotel &

attended a presentation to Mr James Cowie, late Stationmaster at Ballater who

retired last spring …”.

Henry Michie

gradually picked up the pieces of his life and started to take on roles in the

community. In 1906 he became secretary

of the Fraserburgh and Strichen Curling Club and he also fulfilled the role of

interim clerk and inspector for Strichen Parish Council. Henry was elected to the committee of the

Strichen Cricket Club too, where he was a regular player. A fancy-dress ball was held in the village in

early 1909, when Henry attended dressed as a Cavalier and the following year,

he was awarded a certificate in the Strichen Ambulance examinations.

In 1910, Henry

Michie was appointed to a new position as assistant factor on the Raith Estate,

Kirkaldy, Fife. This property was owned

by Ranald Munro-Ferguson, 1st Viscount Novar. John Sleigh supported Henry’s application

with a testimonial in which he said he had developed a high opinion of HM

Michie in the seven years that he was in office at Strichen. A leaving presentation was made to Henry in

November of that year. However, his

ambition was such that from mid-1911 he began applying for factorial

positions. The following year, Henry was

appointed as factor on the Logan Estate in Wigtownshire, where he succeeded the

long-serving Mr MacClew. Henry had been

supported in his application by the dying John Meiklejohn, the factor on the

Novar Estate at Dingwall, who expressed a high opinion of him. Sir Ranald had offered to give Henry a

testimonial, if one had not been forthcoming from the Novar factor. The Logan Estates, which enjoyed a mild

climate, were located on the southern peninsula of the Rhinns of Galloway and

belonged for several hundred years to the McDouall family. In early 1914, Henry was a candidate for the

School Board at Kirkmaidan, Chapel Rossan.

Like his

brothers, Henry Michie was brought up to have an interest in the military and

took an early opportunity to join the Deeside Volunteers in March 1901. “Henry Maurice joined the Volunteers at

Braemar last Saturday altho’ only 15 years old last August”, was the relevant

entry in John Michie’s diary. In August

1914, Britain declared war on Germany and military service suddenly became a

deadly business. In late August, Henry

Maurice Michie was commissioned in the Scottish Horse as a second lieutenant

but not immediately given a posting.

Thus, he was able to attend the marriage of his sister Annie at

Sandringham on 6 April 1915. Henry, a

member of A Squadron, 1st Scottish Horse was posted to Morpeth for training but