Introduction

The “Remarkable

Ogstons of Aberdeen” refers to a family which traces back to Alexander Ogston

who was born in 1766 in Tarves, Aberdeenshire.

About 1785 he moved to the county town and started a business trading in

lint and flax thread. In 1802 his

business diversified into the wholesale manufacture of candles. It became very successful and the story of

this manufacturing branch of the Ogstons has been told elsewhere on this

blogsite, see “The Remarkable Ogstons of Aberdeen:

Flax, Candles and Soap”. Alexander

Ogston (1766) had three sons, Alexander (1799), George (1801) and Francis

(1803). Alexander eventually succeeded

to the management of the candle manufactory and continued the success of his

father. George emigrated to Australia

but proved to be either incompetent or unlucky, because he made nothing of his

life. The third son, Frances, was very

bright and attended Marischal College, Aberdeen, where he graduated with the

degree of MA and then moved to the famous Edinburgh Medical School, graduating

with a Diploma in Medicine in 1824. His

subsequent career was consistently studded with success. He filled the post of Police Surgeon in

Aberdeen, Medical Officer of Health and Professor of Medical Jurisprudence at

Marischal College. Francis Ogston’s life

has been dealt with elsewhere on this blogsite – see “The Remarkable Ogstons

of Aberdeen. Francis Ogston (1803 -

1887), Professor of Medical Logic and Medical Jurisprudence at Aberdeen

University”. Francis Ogston (1803)

had two sons, Alexander (1844) and Francis (usually known as “Frank”), both of

whom became doctors too. Alexander

graduated in medicine from Aberdeen University Medical School in 1865 and

subsequently had a career of diversity and dazzling success. This is his story.

The early

life and education of Alexander Ogston (1844)

Alexander

Ogston (1844), the eldest son of Francis Ogston and Amelia Cadenhead, was born

at Ogston’s Court, 84 Broad Street, Aberdeen on 19 April. This Ogston family house had windows which

overlooked the quadrangle of Marischal College, where the young Alexander first

learned to walk. The connection with

Marischal College and the University of Aberdeen would be maintained for the

rest of his life. Between 1850 and late

1852, Alexander attended Rev Archibald Storie’s school in Dee Street. He was the chaplain to the Aberdeen Royal

Infirmary. The next educational

establishment entrusted with the education of Francis Ogston’s older son was Mr

Alexander’s English School in Little Belmont Street, where Alexander was

adjudged to show “superiority” in reading, gained a merit certificate in

English and a prize for mathematics.

Alexander then moved on to Aberdeen Grammar School where he attended

until late 1858, being awarded merit certificates along the way in both Latin

and Greek. His final educational port of

call before entering university was the Old Aberdeen Gymnasium under headmaster

Rev Alexander Anderson, where he was again a prize-winner in Latin, English and

geometry. While at this establishment,

Alexander Ogston (1844) entered the Marischal College Bursary Competition in

November 1859 and came 27th in the order of merit out of 109

entrants, gaining an award of £6.

Late1859 saw

Alexander Ogston (1844) become a matriculated student at Marischal College to

pursue a course of studies which would have, after the fusion, qualified him to

graduate with an MA degree from the University of Aberdeen. In the winter session of 1859 - 1860, he

studied Greek and Latin under Dr Brown and Dr Maclure respectively. In the remainder of his first year, he is

known to have studied Botany under Dr Beveridge, by whom he was adjudged to

have the best collection of plants and was awarded an honorary certificate. Alexander’s second year of study, 1860 –

1861, involved the study of Greek under Prof Geddes, Latin under Prof Maclure

and Mathematics under Prof Fuller, Botany under Professor Dickie, Chemistry

under Dr Brazier and Comparative Anatomy under Professor Lizars. No record has been found of him graduating at

the end of the session, either in local newspaper reports or in the Roll of

Graduates of the University of Aberdeen, and it appears that he simply

continued during the next session, 1861 – 1862, with studies in the Faculty of

Medicine.

The session

1861 – 1862 saw Alexander Ogston attending classes in Anatomy and Physiology

with Prof Lizars, Chemistry with Prof Fyfe and Dr Brazier, Materia Medica with

Prof Harvey (receiving an honorary certificate) and Surgery with Prof

Pirrie. Alexander spent four months learning

Practical Dispensing with Mr David Reid, the Druggist, and he also attended

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. At the end of

the session, he passed part of his medical graduation examinations. During the following session, 1862 – 1863, he

was taught Medical Jurisprudence by his father, Prof Francis Ogston, Histology by

Prof Ogilvie, Microscopy by Rev John Thomson, Clinical Surgery by Dr Keith and

Clinical Medicine by Dr Kilgour. Alexander also undertook 6 months’ Dispensary

work with Dr Rattray. Prof Fyfe of the

Department of Chemistry died during 1861 and in April 1862, the University

Court voted on his replacement. Dr Brazier,

already a member of academic staff in Chemistry was appointed and Francis

Ogston, Senatus Assessor on the University Court, voted for him.

Alexander Ogston’s medical education continues in Continental Europe

Like his father

before him, Alexander Ogston made a continental tour of medical establishments

as part of his education. This tour

appeared to start in Austria, “I saw Vienna in the winter of 1863”. He lived in Vienna as a student in a small

lodging in the suburb called Alser Vorstadt, which contained the Allgemeines

Krankenhaus hospital. In the university

he was given the title of “Inscribed Extraordinary Student “. Alexander enrolled for courses of Anatomy

under Prof Hyrtyl, Physiology under Prof Brucke, Pathology under Prof Rokitansky,

Clinical Medicine under Prof Oppolzer and Surgery under Prof Dumreicher. His educational experiences there were rather

mixed, since he gained nothing new in some cases, being unable to understand

one lecturer and finding some lecture rooms badly overcrowded. This caused him to change his strategy and,

instead, he enrolled mostly for private classes on new subjects, or ones which

were badly taught in Britain. Amongst

the thousands of students in Vienna, there were only seven from the UK. One important set of classes that Alexander

attended was that by Prof Jaeger on the use of a rudimentary ophthalmoscope,

which training Alexander quickly put to use on his return to Scotland. He also received instruction from Prof Turck

on the laryngoscope, Prof Sigmund on syphilis and Prof Hebra on skin diseases,

including smallpox. Alexander Ogston had

been inoculated with cowpox as a child but found a few smallpox-like vesicles

on his own skin, possibly contracted from an infected patient, about which he

consulted Prof Hebra. His conclusion was

that Ogston had a mild attack of smallpox.

Later (year unknown), Alexander Ogston deliberately infected himself

with smallpox with no significant effect.

Away from medical classes, Alexander Ogston lived a very sociable life,

mixing with students of many nationalities.

Though they drank both beer and wine, accompanied by much singing, Alexander

claimed that they did not get as drunk as his medical contemporaries in

Scotland. Indeed, he subsequently claimed

that he was never drunk in his life. Alexander

was admitted to a society for German-speaking students, ostensibly to improve

his knowledge of the language. Socially,

the members were a mixed bunch, none was rich, and many were poor. They had a convention of making small loans

to each other, but these loans were effectively gifts, because they were never

repaid. Alexander was himself wealthy

enough to join in this convention and he made loans to other students. He also took instruction in fencing, that

very continental activity. All of

Alexander’s foreign friends consumed tobacco, and he picked up the habit of

smoking cigarettes in Vienna, which he subsequently transferred to

Aberdeen. “I think I was the first who

smoked cigarettes in that city – much to the scandalizing of the old-fashioned

ladies and eternal perdition for smoking a cigarette in Union Street in

day-time”. When Alexander left Vienna

his student friends sent him a letter over 10ft long, containing greetings and

farewells, indicating that he had been a popular visitor. One of his friends, whom he met in Vienna,

was William (later Sir William) Stokes (1838 – 1900), the son of the famous

doctor, Prof William Stokes of Dublin.

Ogston and Stokes toured the city together, where they attended concerts

conducted by Johann Strauss II (1825 – 1899), the prominent composer of waltzes. Alexander also enjoyed the opera, especially Richard

Wagner (1813 – 1883), who was becoming popular in the 1860s. Alexander Ogston commented that during his peregrinations

about the Austrian capital, “Several times I saw Kaiser Franz Josef (Kaiser

Franz Joseph I of Austria) driving in the city and, on one occasion, the

Kaiserin Elizabeth, a most lovely woman with whom, like everyone else, I fell

deeply in love”.

William Stokes (1838 - 1900)

Kaiser Franz Joseph I of Austria

Kaiserin Elizabeth of Austria

Francis Ogston

had supplemented his medical education with a visit to Continental Europe in

late 1824. Though the details have not

been uncovered, he studied at several leading medical establishments before

returning to Scotland. In session 1863 –

1864, his son, Alexander followed a similar, but apparently more extensive,

sojourn across the North Sea, travelling on from Vienna to Prague, where he

appears to have met up with his father.

It is unclear what specific activities they undertook together but

Alexander commented, “No classes but attended Seifert, Maschka and Hasner at

University and Hospital”. Ostensibly,

Alexander had gone to Prague to improve his knowledge of the German

language. He also attempted to learn the

Bohemian language but gave up on account of its complex verbs. Alexander Ogston developed contrasting

opinions about the three main ethnic groups in Prague. “A strange population filled the crowded

town. Half the inhabitants were Czechs

(Bohemians), a quarter were Germans, and the rest were Jews”. He found that the Bohemians hated the

Germans. “The Jews mixed with both and

permeated the ranks of both …”. “My

acquaintances were mostly among the Germans and Jews, many of whom were intermarried,

some for generations so that it was not always an easy thing to judge whether

they were of pure blood. I came to love

the Jews; their intellectuality was so outstanding and the eminent rank they

held in the medical profession, in the University circles and in the society

which I frequented compelled respect and esteem”. “I attended the Medical Society of the

city. It was housed in no fine building

– although there I met with the famous Professor Czermac, the inventor of the

laryngoscope; Professor Prsibram; Professor Kahler, Professor Maschka of

Medical Jurisprudence and Professor Ritter von Ritterstein who edited a

magazine devoted to the diseases of childhood; and others equally eminent – its

meeting place was just a small box, one of many in a public house, where there

was barely room for the nine or ten members to find accommodation”. “Everyone was kind to the young Scot but with

the Bohemians I always felt the constraint of an alien race whom I could not

see through. This was less so with the

Germans but on the other hand with the Jews I felt at once quite at home. I was constantly at the houses of the

Maschkas and their friends and many years afterwards when those of the Maschkas

who survived were suffering from poverty, especially after the Great War when

starvation was rife in Vienna, whither they had gone, I was able to do

something to alleviate their distress”.

The sojourn in

Prague lasted for two months before Alexander Ogston, again in the company of

William Stokes, travelled on by train to Berlin, where the pair took lodgings together

near the Charité Hospital. By this time,

it was the start of the 1864 summer session at the University of Berlin, where

Ogston and Stokes were probably the only British students in attendance. This institution was famous for a number of

leading doctors and scientists on its staff.

The two young British doctors attended the following lecture

courses. Ophthalmology – Prof Albert von

Graefe, Pathology – Prof Rudolf Virchow, Demonstrations – Prof Kuhne and the Clinics

of Prof Langenbeck, the prominent surgeon.

Von Graefe was one of the leading proponents of the ophthalmoscope,

which had been invented by Hermann von Helmholz in 1850. At the 1858 Heidelberg Ophthalmological

Congress, von Graefe presented Helmholtz with a cup which was inscribed with

the words, "To the creator of a new science, to the benefactor of mankind,

in thankful remembrance of the invention of the ophthalmoscope". Virchow,

though a disappointing lecturer, was something of a polymath and became

particularly famous for propounding the cell theory, one of the most

fundamental generalisations in Biology.

This theory states that cells are the basic units of life, that cells

only arise from the division of pre-existing cells and that life is transmitted

from one generation to the next by cells.

After the

completion of their studies, the two young medics travelled together in Bohemia,

Saxony, Switzerland and Prussia, visiting Thuringia and the Hartz mountains,

and Dresden with its art galleries. The two also visited various historical

sites and, with the encouragement of a corrupt guardian of objects which were

associated with Martin Luther at one of them, Alexander took samples and, when back

in the UK, he preserved and labelled these items and displayed them in a glass

case. In Cologne they visited the

church of St Ursula and were told a traditional, if fantastical, story of a

visit to Rome by St Ursula, accompanied by 11,000 virgins. On her return she and her followers were

murdered by the Huns and the skulls and other bones of these martyrs were

subsequently stored in the church.

Alexander examined these remains with his medical eye and found that at

least some of the bones were derived from bullocks!

Alexander

Ogston found a marked contrast in people’s behaviour between Austria and

Germany, though both were German-speaking.

Austria was a nation of gentlemen, while Germany was a nation of boors

and bullies. People barged him off the

pavements and men had an unpleasantly superior attitude to women. They also disliked foreigners. “Englischer Schwein”, accompanied by a scowl

being common amongst railway officials at all levels. This was the time of the Second

Schleswig-Holstein War, which lasted from February 1864 to the end of October

of the same year, when Denmark, much the smaller state, was attacked by Prussia

and Austria. Alexander found the

Prussians to be very boastful of their military prowess. “We had ample opportunity of watching the

development of the modern German bully, though we had little thought then of

the menace that the brute would become in Europe in the next fifty years”. Alexander also found German triumphalism in

defeating Denmark very distasteful.

“When the King came out to the balcony of the Royal Palace and addressed

his people amid the most frantic manifestations of joy and loyalty, Stokes and

I laughed at the performances”.

Despite his

dislike of the popular attitudes and manners of the generality of the German

population, Alexander Ogston, by this time fluent in German, would return to

the country many times, would attend German medical congresses, would become a

familiar of leading German doctors and would publish important scientific

findings in German periodicals. “Owing to my friendship with these men (the

professors in Berlin) I soon came to know others such as Esmarch of Kiel,

whose name became great in connection with bloodless surgery and in after years

I met them at Langenbeck’s house and elsewhere”. Alexander was the direct recipient of a

particular instance of German unpleasantness.

He gave a lecture to the Congress of German Surgeons and Volkmann,

although not personally present, attacked the visiting Scot the next day,

describing his methods as “surgical rope-dancing”. However, Volkman was known to be a morphine

addict and Ogston did not reply, believing that the German was acting under the

influence of this addictive, mood-altering opiate.

Ogston and

Stokes, the young medical wanderers finally ended up in Paris for further study

before Alexander Ogston returned to his native land and the completion of his

undergraduate medical courses. He

graduated both MB and CM during the spring and summer of 1865, “with Highest

Academical Honours”, one of eight graduands to do so. About a year later he was also awarded the

postgraduate qualification of MD, again “with Highest Honours”, the capping

ceremony taking place in the public hall at Marischal College in April

1866. For Alexander Ogston, son of a

prominent medical father, scion of a wealthy Aberdeen family of manufacturers,

familiar of leading German doctors and a fluent German speaker, the scene was

set for him to pursue a prominent medical career. He did not fluff his chance but, at this

auspicious beginning of his professional life, he could not have guessed how

successful he would become.

Alexander

Ogston and boats

Although little

is known about Alexander Ogston’s sporting activities as an undergraduate, it

is likely that he was a keen oarsman, but this is only known from two

advertisements placed in the Aberdeen Journal in 1865, offering for sale a

four-oared racing gig, “Bon-Accord” and a five-oared boat, “Black Bess”, “with

new oars and fittings complete”. This

was the year that Alexander graduated from the Aberdeen Medical School and

began remunerated work. Perhaps he felt

that he could no longer spare the time necessary to pursue this challenging

activity? A few years later, after he

had acquired the Glendavan estate, which encompassed part of Loch Davan, in

1888, he is known to have kept a rowing boat there, probably to allow him to

fish for pike and perch, but he also used to row his young children around this

expanse of water on quiet evenings.

Alexander

Ogston and Ophthalmology

During his

continental foray into the universities and hospitals of Europe, Alexander

Ogston had received training in the use of the ophthalmoscope from von Graefe

and others, and he soon put this skill to good use by opening an eye dispensary

in Castle Street, Aberdeen in 1866 which it is presumed catered for the needs

of the poor people of Aberdeen. The

dispensary did not survive for long, being closed in 1868, perhaps due to

Alexander being appointed in that year as Ophthalmic Surgeon to Aberdeen Royal

Infirmary. The appointment came about

after the resignation of Dr Wolfe from the position of Physician to the

Ophthalmic Institution in September 1868.

There were two applicants for the post, Dr Alexander Ogston and Dr

Alexander Dyce Davidson. The directors

of the Institution then, perhaps unwisely, asked Dr Wolfe for his opinion of

the two contenders but Ogston, when he heard of this development, was clearly

miffed. Subsequently, the directors met

to consider how to proceed, when they received a letter from Alexander Ogston

rejecting the notion that Dr Wolfe should have been asked, in effect, to

arbitrate between the two candidates.

This did not advance the directors’ opinion of Alexander, who was

rejected for the role by a vote of 10 : 3 in favour of Dr Davidson. But that was not the end of the matter since

the actual employer of the postholder would be Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. On 28 September 1868, there was a Special

General Court of the Managers of ARI to consider the appointment to the post of

Ophthalmic Surgeon. The Lord Provost,

Alexander Nicol, chaired the meeting, which was attended by many managers, and

he got straight to the point. Without

asking for formal nominations of the candidates, he posed the question, “There

are only two candidates, do you want to proceed at once to an election”? There was general and enthusiastic acclaim for

this proposal. It appeared that the

managers were already familiar with the credentials of the two competing

doctors and had made up their minds. The

vote went in favour of Alexander Ogston by 70 : 52. Davidson must have felt a

bit hard done by, after he had already received the approval of the directors

of the Ophthalmic Institution. Alexander

Ogston’s undoubted medical abilities, which had already come to the fore,

clearly outweighed the blunt way in which he had demonstrated his disapproval

of the Institute’s managers. Most

interesting to contemporary eyes was the advertisement placed by Alexander

Ogston in the Aberdeen Journal following his appointment as Ophthalmic Surgeon

at ARI. “Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

Election. Dr Alex Ogston takes this

opportunity of returning his thanks to the Managers for their support at the

election today and hopes to merit the confidence reposed in him. Aberdeen 28 September 1868”.

The new

ophthalmic surgeon wasted no time in organising his charge. The Aberdeen Journal reported that at the

next quarterly meeting of the ARI managers, “Surgical instruments to the value

of £10 10s have been added to the stock of the Ophthalmic Department of the

Hospital and a favourable arrangement entered into with Dr Ogston with the view

of making that department efficient and complete”. Interestingly, one of Alexander Ogston’s

duties in addition to acting as Ophthalmic Surgeon, was to act as anaesthetist,

this technique being newly introduced into surgical practice. After starting his newest position, Alexander

also delivered three courses on the use of the ophthalmoscope over the winter

of 1868 – 1869. In April 1869, Alexander

Ogston asked the University Court to fix the fee for his Ophthalmology course

at 1gn. At the end of his courses on the

use of the ophthalmoscope in April 1869, his medical students who had attended these

classes presented him with a testimonial, suggesting that his lectures had been

well received. About this time,

Alexander was appointed Lecturer in Practical Ophthalmology in the University

of Aberdeen. During the summer term of

the 1870 – 1871 University session, Alexander Ogston again mounted a

three-month course in Practical Ophthalmology, but this would be his last such

teaching assignment as he was appointed Junior Surgeon at ARI in August 1870

and resigned his appointment as Ophthalmic Surgeon the following month,

followed by him giving up his university lectureship in Practical Ophthalmology

in the following November. In future,

though he would operate on patients with damaged eyes, his surgical horizons

would be much more extensive than the organ of sight.

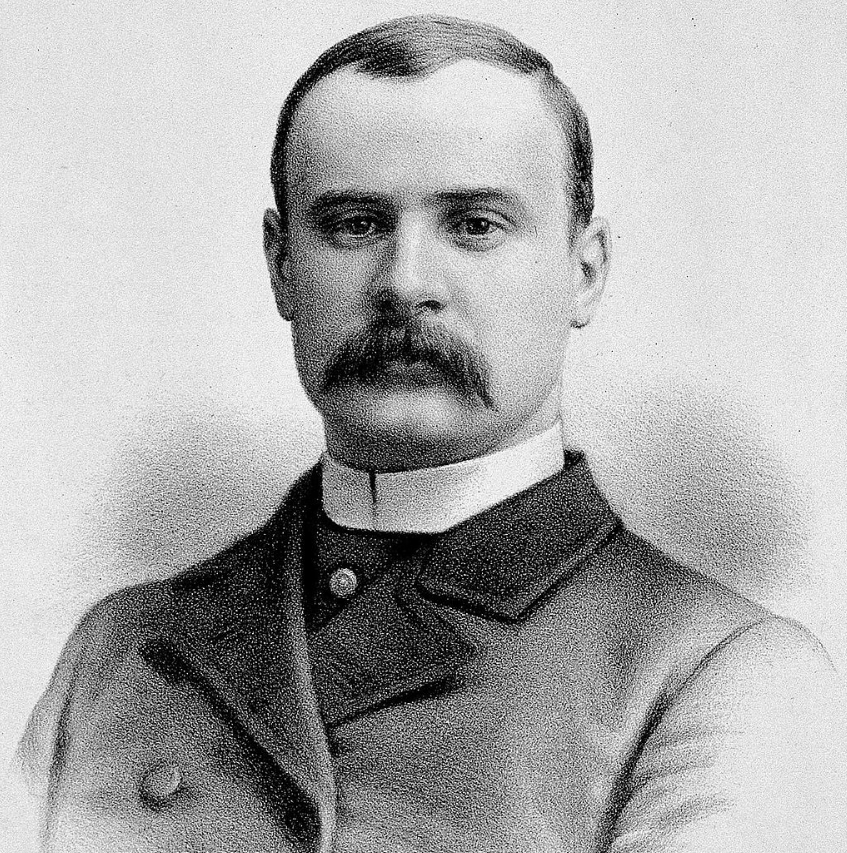

Alexander Ogston

Alexander

Ogston marries Mary Jane Hargrave

Alex Ogston

married Mary Jane Hargrave on 25 September 1867 at Stoke Newington,

Middlesex. She was the fourth child and

younger daughter of James Hargrave, who had a substantial career with the

Hudson Bay Company in Canada, rising to become the Chief Factor in 1844. Mary Jane’s father had been born in Hawick,

but Mary Jane emerged into the light at Sault Ste Marie, in Ontario. During 1858 – 1859, her father took a year’s

leave of absence in Scotland before remarrying and returning to Canada. It seems likely that Mary Jane then remained

in Scotland. Presently, it is unclear

how she met Alexander Ogston. On

marrying, Dr Alexander Ogston moved out of his father’s house at 156 Union

Street, Aberdeen to his own property at 193 Union Street, until 1871, when he

moved again to 252 Union Street. This

remained his Aberdeen town house for the rest of his life.

Mary Jane Hargrave

The first child

of Alex and Mary Jane Ogston, Mary Letitia, was born 8 months after the

marriage, followed by Francis Hargrave in 1869, Flora McTavish in 1872 and Walter

Henry on 29 November 1873. After this

fourth birth, Mary Jane suffered from what was then called puerperal mania, now

referred to as postpartum psychosis. It

is a severe mental illness which usually starts within a few days of birth but

is now thought not to be a single condition but a complex of many different

maladies with overlapping and varying symptoms.

In those days this illness could be fatal, and this was the case for

Alex Ogston’s wife. She died on 28

December at 252 Union Street, barely a month after the birth of her fourth

child. The cause of death was certified

by “F Ogston, MD”, probably Francis Ogston senior, though the informant,

present at the passing and who registered the death, was Frank Ogston

junior. This was a crushing blow for

Alexander Ogston and left him to look after four young children aged from 5½

years to one month. Three and a half

years would pass before Alex Ogston married again.

Alexander

Ogston and Homeopathy

Homeopathy is a

system of alternative medicine which was created by the German physician Samuel

Hahnemann in 1796. Its principal beliefs

are that a substance that causes certain symptoms in healthy people can also be

used to cure the same symptoms in sick people.

These, so-called, remedies are prepared by making extreme dilutions of

the material before administration. It

is entirely unscientific, being unsupported by experimental results and

considered to be fake by the scientific medical community.

In December

1868, a meeting of the Court of the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was held with a

“very large attendance of managers”. The

reason for such a populous meeting was that a controversy had arisen as whether

it was appropriate to allow homeopathic treatments to be administered to

patients in ARI. Dr Reith, one of the

physicians at the infirmary, was proposing to use homeopathic remedies in his

hospital practice but all the other physicians and surgeons were opposed to the

proposal. Lord Provost Alexander Nicol

was president of the court and it fell to him to conduct the meeting.

William

Dingwall Forsyth, MP for Aberdeenshire East wrote a letter proposing a

compromise. It would have involved Dr

Reith being reappointed as a physician but only prescribing homeopathic

treatments in separate wards to those patients requesting them. He wanted to see “harmonious cooperation

between medical officials at the infirmary”.

But such a solution was quite unworkable. Dingwall Forsyth had not appreciated the

utterly fundamental gulf between evidence-based medicine and the alternative

which depended only on believing that homeopathy was valid. The Lord Provost had referred the dispute to

the judgement of two doctors of great status in the area, Drs Kilgour and Dyce. Their conclusion was that any encroachment of

homeopathic practices on the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary would lead to “very

serious consequences for the institution”, though they had no objection to any

doctor providing such treatment to his private patients. The Lord Provost said that he personally

accepted this judgement because of the status of the two authors of the study

but that point of view was also held by other doctors in the city and the

country round about, which reinforced his position.

The Lord

Provost then put forward a motion for consideration. “The managers having had under consideration

the correspondence between Drs Harvey, Smith and Reith and also the report of

the two Consulting Physicians thereon consider it to be for the best interests

of the institution to be guided by that report and not to permit the use of

Homeopathic medicines in the Infirmary, further having regard to the

correspondence and various publications which have been furnished by these

medical gentlemen to the managers as well as to the almost unanimous expressed

opinion of the medical men of the city and district which is entirely adverse

to the practice of Homeopathy they do not consider it advisable to give

countenance to it within the Institution”.

The motion was met with applause.

The president

then revealed that he had received a letter from all the doctors at the

infirmary, except Dr Reith, but had not circulated it because he did not want

it to appear as a threat. There was then

a clamour from the meeting for the letter to be read out and the president

complied. “Aberdeen 12th December

1868. To the President and Managers of

the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. Gentlemen,

Whereas Homoeopathy has not received the sanction of the medical profession and

whereas it is in our opinion both unsound and irrational we the undersigned beg

with all respect to acquaint you with our conviction that it would not be

honest in us to remain connected with an institution in which that system is

recognised. We have no right nor have we

any desire to dictate to you in regard to the choice of any of your medical

officers. If it be your pleasure on

Monday next to re-elect Dr Reith well and good; but in that case, we consider

that you will thereby virtually give your sanction to the introduction of

Homoeopathy into your Institution.

Therefore, in that event and in the event also of our own re-election,

there would be but one course open to us, namely that of resignation. Thanking you for the consideration you have

always shown us and for the confidence you have hitherto placed in us, we have

the honour to be, Gentlemen, Your most obedient Servants. Rd Dyce, Al Kilgour, Wm Keith, William Pirie,

David Kerr, Alex Harvey, JWF Smith, Alex Ogston”.

The motion was

then put to the meeting and Dr Reith’s few supporters then showed themselves,

but they concentrated their fire on the physicians and surgeons who had written

the letter threatening resignation.

Principal Campbell from the University rejected this view and said it

had been right for the letter-writers to make their view clear before the

meeting. Dr Pirie also thought the

medical men had acted honourably in making their views known before the vote

and thus preventing a decision “to plunge into a course of action which would

have thrown the whole Infirmary into confusion”. He also described Homoeopathy as “absurd,

false and delusive”. “We, as the

representatives of the public, are responsible.

The poor have been spoken of. We

are the trustees for the poor in that matter”.

Major Innes of Learney regretted that the debate had taken place with such

“heat, partisanship and intemperance”. He

proposed his own motion removing the banning of homeopathic medicines from the

institution. He found no seconder and

the president declined to modify his motion.

This was then passed by a large majority; the opponents being allowed to

record their dissent in the minutes.

At that time,

Alex Ogston was the Ophthalmic Surgeon at ARI, the most junior staff position,

hence his placing last in the list of signatories. Perhaps he had little option but to agree with

his elders and betters, but it is certain that, even at this early stage in his

career, his commitment to scientific medicine was unshakable and he would have

had no qualms in refusing to be associated with what he viewed as quack

practices.

Alexander Ogston

becomes Joint Medical Officer of Health for Aberdeen

During March

1868, the Public Health Committee of the Town Council requested Francis Ogston

to name a substitute to act for him, when necessary, through absence or

otherwise and he named his son, Alexander Ogston (1844). However, he could not be appointed as

substitute for his father as the Public Health Act did not allow such an

arrangement. Instead, he was appointed

Joint Medical Officer of Health for Aberdeen, the existing salary of £43 10s

being shared by the joint postholders.

Although nominally equal in rank to his father, in practice Alexander

was very much an apprentice in the role.

He continued in post until 1873 when he resigned due, as will be seen,

to a major disagreement with the city authorities.

Alexander

Ogston and the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

Alexander

Ogston (1844) first became acquainted with Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, then

located on the Woolmanhill site near the centre of town, in 1862 during his

medical training. At that time, the

conduct of surgical operations and the organisation of the wards to which the

patients were sent after surgery was primitive and, to modern eyes, truly

horrific. Antiseptic surgery was yet to

be invented and chloroform-induced anaesthesia was a new technique, still to

receive a nod of approval from many leading surgeons. Alex Ogston noted that in Aberdeen, although

tentatively favoured by the younger surgeons, chloroform was usually not

employed, due to the views of William Keith, the First Surgeon at ARI, known as

“Old Danger”, to the medical students.

Keith had somehow developed the opinion from his own experience that his

operations were more successful when anaesthesia was not used. However, by the time that Alexander Ogston

graduated in 1865, chloroform anaesthesia was generally accepted as a major aid

to surgery. If anything, the conduct of

the wards was even more frightening than the conduct of operations. Each ward was overseen by a fat old woman who

prepared poultices. She invariably kept

a pet tomcat, which bore the name of the doctor that she served, for example

“Alexander Kilgour”, the Senior Physician at ARI. As tomcats do, these animals patrolled their territories,

including the operating theatre, scent-marking prominent objects with a spray

of smelly urine. Added to the

characteristic stink of tomcats was the equally recognisable stench of

suppuration in surgical wounds which, in those days, usually became infected

after an operation. There was no

understanding of the importance of cleanliness, there was no provision for

hand-washing and surgical instruments and other accoutrements were simply

placed on an open shelf when not in use.

Operations were performed by surgeons dressed in their street clothes,

overlaid with one of a collection of communal long black coats. These garments were never washed and became

encrusted with blood, tissue and the contents of body cavities. This was the environment that Alexander

Ogston entered when, in 1870, he was appointed to the post of Junior Surgeon at

ARI.

The surgical

hierarchy in 1870 consisted of four positions, First, Second, Third and Junior

surgeons. Generally, when one surgeon

died, retired, or otherwise demitted office, the person or persons below him in

the pecking order moved up a rung on the surgical ladder and, finally, there

was a competition for the most inferior role.

In that year William Keith, First Surgeon, resigned and those below him

shuffled up with aspiring surgeons then putting their names forward for the

vacant position of Junior Surgeon. The

candidates included Dr Alexander Ogston, Dr Alexander Dyce Davidson, Dr Best,

Dr Ogilvie Will and Dr Roger. At a Royal

Infirmary Special General Court held at the beginning of August 1870, a vote

was held on the list of candidates, with the following result. Ogston 63, Davidson 30, Best 23, Will

16. Although Alexander Ogston had

garnered 33 votes more than Davidson, the claim was made by one or more

managers that the result was not clear-cut, suggesting that there was some

lingering hostility to this brash young surgeon. Dr Will was then dropped from the list, the

poll re-run and the following count declared, Ogston 71, Davidson 34, Best 28. This time the result was allowed to stand,

and Dr Ogston was duly elected though, in truth, the outcome was little

different from that previously obtained.

Alexander Dyce Davidson had again been vanquished by Alexander Ogston in

an employment competition, but Davidson received a consolation prize shortly

afterwards when he was appointed to the vacant post of Ophthalmic Surgeon. He had been the only candidate. Alexander Ogston again took space in the

Aberdeen Journal to thank those responsible for his appointment. “Royal Infirmary Surgeoncy. Dr Alex Ogston begs to convey to the

Infirmary Managers his thanks for the honour conferred on him on Friday last”. The position of Junior Surgeon was not

remunerated and involved very little work, other than acting as anaesthetist

when required. In order to keep himself

busy, Alexander applied for, and was additionally appointed to, the position of

Aurist at the infirmary in 1870.

Alexander

Ogston is appointed as Assistant Professor of Medical Jurisprudence

This university

appointment in 1870 was in the gift of his father, but there was no hint that

anyone found this situation to be unacceptable and potentially a case of

nepotism, perhaps because Alex Ogston was such an outstanding young doctor and

had experience of police work as assistant to his father. This post was renewed annually until 1873,

when Alexander Ogston resigned the position.

Alexander

Ogston and German behaviour and attitudes

Alexander

Ogston attributed the deterioration in German behaviour and social attitudes to

their drubbing of the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1871 – 1872. “After the Franco-Prussian War, the simple

modes of life came to be altered and luxury and ostentation were increasingly

evident in their dwellings …”. And in

other aspects of German life, “Arrogance and boastfulness crept in and took the

place of the former quiet conduct while the demeanour of the officers of the

army in public places became bullying and self-assertive to an offensive degree

and was plainly cultivated as a mark of the military official. … The gentle

quiet studious type of German medical man died out by degrees and the type of

the warrior was substituted, nearly all the leading surgeons being attached in

some fashion … to the army. One by one I

missed the plain homely persons I had known so well …”. Langebeck developed cataract and had to

retire from surgery and take up general practice. He lost his fortune apparently due to some

bad behaviour by a relative and died essentially in poverty. Alex Ogston had found this man to be

inspirational, not only for his country but also for Ogston personally. Some of the new breed of German surgeon, Alexander

Ogston both knew and liked but others, already famous, he hardly spoke to. He also found an undercurrent of anti-English

feeling. He knew three German surgeons

very well. Frederick Trendelenburg,

Professor of Surgery at Leipzig University, visited Alex Ogston in Aberdeen in

1906, staying with him at 252 Union Street and was honoured with the award of an

honorary LL D from Aberdeen University.

Mikulicz “was a good fellow” whom Ogson met again in Glasgow when both

were guests of Professor Macewen. Carl

Lauenstein was the third and Alex Ogston sometimes stayed at his house in

Hamburg. He and his family were

repeatedly the guests of the Ogstons in Aberdeen and at Glendavan. He even travelled through Scotland with the

Ogstons at Alexander’s expense. Ogston

was not pleased when, on the outbreak of war in 1914, the German wrote a book,

or pamphlet, abusing the British and their ways. Alexander Ogston’s admiration of, and respect

for, German science and medicine clearly overcame, for some time, his distaste

for the social attitudes frequently on display in the country. But Germany’s appeal for Alexander Ogston started

to wane. “In course of years however,

the attractions of German science became less for me and the changed character

of the people so repellent to me that I withdrew from the membership of the

Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie”. Alexander

Ogston then turned his attention more to North America, though apparently he

never travelled there.

The

influence of Joseph Lister on Alexander Ogston

Joseph Lister

was born into a prominent Quaker family at Upton, Essex, in 1827. At the age of 17 he entered University

College, London to study medicine and was present at the first operation

performed under ether anaesthesia almost three years later but was shocked to

find that mortality following apparently successful operations was depressingly

high and concluded that surgery should only be performed if absolutely

necessary. He also developed an

antipathy to osteopaths whom he regarded as charlatans. Lister graduated with the degree of MB from

the University of London and also gained a Fellowship of the Royal College of

Surgeons. Joseph Lister then moved to

Edinburgh Royal Infirmary to work under Professor Syme, a man of great status

and trenchant opinions. The two became

friends and Joseph Lister married Syme’s daughter, Agnes.

Lord Lister

In 1860, Lister

was appointed Regius Professor of Surgery at Glasgow University, though for a

year he was without a complementary hospital appointment. The 1850s and 1860s were a time of great

ferment in the field of microbiology with the progressive demonstration that

some diseases were caused by microbial infections. But the significance of microbes was not

fully understood, especially by the surgical establishment which generally

regarded them as microscopical curiosities of little significance. Hospital diseases such as erysipelas,

pyaemia, septicaemia and hospital gangrene were often dismissed as unavoidable

evils, or even as a necessary part of the healing process. The miasma theory, which held that foul air

was the cause of disease transmission, still held sway and seemed to explain

the observation of passage of disease from one inmate to another in crowded

wards containing patients with suppurating wounds.

Louis Pasteur

Between 1860

and 1864, Louis Pasteur demonstrated that fermentation in nutrient broth was caused

by microorganisms carried in the air and was not due to spontaneous

generation. Lister himself believed in

the miasma theory until 1865 when he became acquainted with Pasteur’s work. However, he still had no idea of the

universality or diversity of microorganisms in the environment. Between 1858 and 1863, Lister conducted a

series of experiments on inflammation and blood clotting, the results of which

were published. Inflammation preceded

suppuration in surgical wounds and Lister was trying to understand the

processes by which suppuration was generated.

Joseph Lister concluded that microorganisms carried in the air were

probably responsible, in some way, for suppuration and that cleaning the air in

contact with a wound of microorganisms by chemical means was the way

forward. Occasionally, compound open

fractures presented for his attention and in 1865 he first used carbolic acid

in an attempt to suppress the disease processes which were inevitable in such cases. From this time, Lister was totally focussed

on preventing suppuration rather than improving surgical technique. It was May 1866 before he had another

suitable compound fracture case to try out his new technique. This was a seven-year-old Glasgow lad who had

sustained a leg break after a cartwheel rolled over him. Lister applied a piece of lint dipped in

carbolic acid solution to the wound and four days later when he replaced the

pad found that no inflammation had developed.

Six weeks later the broken leg bones had fused back together and there

was no pus in evidence.

Joseph Lister

published his results in a paper which appeared in a series of parts in the

journal, “The Lancet” between March and July 1867 under the general title of “On

a new method of treating compound fracture, abcess, etc with observations on

the conditions of suppuration”. While

his results were well-received in Germany, they failed to win over the

conservative surgical establishment in Britain, especially in London, where, by

and large, the claims were treated with incredulity. Rickman Godlee, Lister’s biographer argued

that a different style of training in Germany was responsible for this

divergence of opinion. Lister’s results

were derived from scientific experiments which German doctors understood

because they mostly took science degrees, whereas in Britain, surgeons were

taught practically, standing in the shadow of their opinionated masters. However, rivalry and jealousy were not

uncommon in the medical profession and may have played a part in the rejection

of Lister’s claims. Even two years

later, at the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting held

in Leeds, Joseph Lister’s techniques were mocked by the surgical

establishment. Also in Leeds, at a

meeting of the BMA in the same year, Mr Nunneley, the prominent Leeds-based

surgeon disparaged Lister’s methods, though he had not tried them

personally. However, other attendees had

trialled Listerism and found that it worked, and they spoke up in his support.

Lister

described his initial version of the antiseptic surgical technique as

follows. “Clean the broken limb, squeeze

out all blood clots, swab the inside of the wound with calico soaked in

undiluted carbolic acid, cover the wound with a piece of lint also soaked in

carbolic acid, cover that with a metal sheet to prevent evaporation. Leave for several days and renew carbolic

acid from time to time”. In the period

1865 – 1868, Lister also experimented with a carbolic spray for cleaning the

air, the wound and the skin around the wound.

Carbolic acid is not very soluble in water, about 8% being a saturated

solution, and such a solution was generally used in the sprays which were

further developed after Lister’s return to Edinburgh in 1869. Lister also emphasised the importance of

cleanliness of hands, clothes and instruments.

Many other

doctors visited Lister in Glasgow to see for themselves the results of the

antiseptic surgical technique. Also,

Lister’s own junior surgeons eventually moved away to significant positions

elsewhere and became ambassadors for his methodology. But Lister’s ideas were rejected by all but

one of his senior colleagues at Glasgow.

In August 1869, Joseph Lister was appointed to the Chair of Clinical

Surgery at Edinburgh University in succession to his father-in-law, Professor

Syme. Sadly, in Edinburgh too, Lister’s

pronouncements on antiseptic surgery were rejected by all his senior

colleagues. It was about this time of

transition, though the actual date has not been uncovered, that Alexander

Ogston decided to make contact with Joseph Lister. Ogston later wrote, “Unforgettable was the

incredulity with which we heard the first announcement that Lister had

discovered a means of avoiding suppuration and blood poisoning in operation

wounds”. Ogston then took a very bold

step for a decidedly junior ophthalmic surgeon from Aberdeen, who had not even

reached the lowest rung of the surgical hierarchy at Aberdeen Royal

Infirmary. He called, without

introduction, on Lister at his home in Edinburgh, where he was received cordially. Alex Ogston then went on to Glasgow,

presumably at the suggestion of Joseph Lister, and was shown around Lister’s

wards there (24 and 25), possibly by Dr Archie Malloch, a 25-year-old Canadian

doctor with Scottish ancestry who had been training with Professor Lister in

Glasgow and who took charge of his wards in the absence of the boss. Ogston was convinced of the veracity of

Lister’s claims within five minutes of walking the Glasgow wards. Malloch later married Alex Ogston’s younger

sister, Helen Milne Ogston (1849). Is it

possible that the couple met in Aberdeen when Malloch was making a reciprocal

visit to Ogston’s home? They were joined

in 1872 at Brockville, Ontario but tragedy struck only a year into the marriage

when Helen Milne contracted diphtheria, which attack proved to be

terminal.

In 1869, Lister was initially convinced, based upon the work of Pasteur and others, that the air was the route by which microorganisms gained access to wounds, which caused him to concentrate on the further development of the carbolic acid spray. The bulb spray already existed but further versions were invented, firstly a foot-controlled bellows spray, then a spray mounted on a tripod with a hand lever to pump out the fluid droplets and finally a steam-actuated spray. Later, in 1891, Alexander Ogston published a paper in “The Lancet” describing an "irrigator regulator" invented by Mr TW Ogilvie, one of the most outstanding medical students of his year, which was used for spraying wounds with antiseptic preparations during surgical operations. The instrument was made by Mr John Stevenson, Schoolhill, Aberdeen. Thomas White Ogilvie graduated MB CM in 1892. He hailed from Keith in Banffshire and lived an amazingly varied but brief life, dying in 1908.

Ogston returned to Aberdeen in late 1869 convinced that Lister’s methodology would greatly reduce the incidence of post-operative wound disease, but it was only in 1870 that he was elected to the post of Fourth or Junior Surgeon, unpaid, not in charge of any operations and lacking influence with the big beasts ahead of him in the surgical hierarchy. Even in 1874 when he became Third Surgeon and could undertake his own operative procedures and guide his own trainees, his influence was limited, though he now had Dr Ogilvie Will, with whom he saw eye to eye on Listerism, below him in the hierarchy. In 1876 he became Second Surgeon and in 1880 he ascended to the top job of First Surgeon, all the time pressing forward with the application of Listerism in Aberdeen. But it was only in this year, with the retirement of Prof William Pirrie, that Ogston was completely free to promulgate Lister’s methodology. Pirrie believed that acupressure could be used not only to stem bleeding from cut blood vessels but also to control suppuration of wounds, though Ogston and others at ARI knew that Pirrie’s results on the impact of acupressure on suppuration were false and due to his nurses assiduously wiping all traces of pus from operation wounds before Pirrie made his ward rounds. The detailed progress of Ogston’s pioneering introduction of Lister’s techniques into surgical practice in Aberdeen after 1869 has not yet been fully uncovered but one excellent insight was produced by Dr John Scott Riddell, who graduated from Aberdeen Medical School in 1886 and later became senior surgeon at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. In 1886 Riddell was acting as chief dresser in Professor Ogston’s wards at ARI and was closely associated with Ogston’s work for seven years subsequently, both in the infirmary and in the university. He described Ogston’s struggles with Lister’s detractors in the following terms. “(Ogston was) A convinced believer in the germ theory (the belief that many diseases are caused by infections by specific microorganisms) and in the practice of Lister, he helped to build up and improve its methods and was able to demonstrate to a generation of students and the profession generally its safety and its infinite possibilities. But there is always a Mordechai in the gate. The opposition and persecution which Lister met with in Glasgow, Edinburgh and London was not wanting here (Aberdeen) and protagonists of the Listerian dogma in Aberdeen had to fight for their opinions. Indeed, some of the unconverted had been heard to say that if they could get a sufficient number of germs to make soft pads, they would dress their surgical wounds with them! Dr Riddell went on to describe the operation of the steam spray. “This “Puffing Billy” was an infernal machine which occasionally blew up and which I am afraid caused many finger burns and much profanity. … I recall the wards of bygone years and conjure up the sounds of steam sprays, hissing and spluttering a tainted atmosphere, redolent of carbolic acid and iodoform (an early anaesthetic), varied with occasional whiffs of the concentrated effluvia of soft soap and perspiring humanity”.

William Bulloch

(1868) graduated MB CM from Aberdeen University in the class of 1890. Other than sharing a surname with John

Malcolm Bulloch, there is no direct evidence that he was involved in the

writing of the “A.O.” poem. But, as will

be seen, he would have been qualified to do so.

William Bulloch became a bacteriologist and would later confess his admiration

for Alexander Ogston, who was one of his teachers. After several significant

postings, Bulloch was appointed Professor of Bacteriology at London University

in 1917. He was also the author of a

seminal work, The History of Bacteriology, published in 1938, which dealt with

the significance of Ogston’s work for the development of Bacteriology. Bulloch also wrote an appreciation of

Alexander Ogston’s life, which was published in the Aberdeen University Review

in 1929. Apart from Ogston’s ground-breaking

work on bacterial suppuration, Bulloch considered Alexander Ogston to have been

“the greatest practical doctor that Aberdeen had produced”.

“A.O.”

Then we came to the land of the dummy,

To learn how to handle the knife;

The thing to begin with was rummy,

But rummy sensations were rife,

The plan of inserting a suture

Was taught in a practical way,

And we learned that the thing of the

future

Was using unlimited spray

,

The spray, the spray, the antiseptic

spray

A.O. would shower it morning, night and day

For every sort of scratch

Where others would attach

A sticking plaster patch

He gave the spray

To perform an abdominal section,

To strengthen a shaky knock-knee

Were things he could do to perfection –

To this you must surely agree,

And few were his words, and his manner

Was always deliberately slow;

As long as we flutter life’s banner

We’ll always remember A.O.

A.O., A.O., the dignified A.O.,

The solemn Prof. who garbled no bon mot.

This great and gallant man

Explored the hot Sudan;

Got medals spick and span –

You know, you know.

After

the initial contact between Ogston and Lister in Edinburgh, a mutual respect

grew between the two men and they became good friends. In 1883, Ogston wrote in a letter to Lister,

“You have changed surgery, especially operative surgery from being a hazardous

lottery into a safe and soundly-based science.

You are the leader of the modern generation of scientific surgeons and

every good man in our profession – especially in Scotland – looks up to you

with such respect and attachment as few men receive”. Lister reciprocated these sentiments in his

presidential address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science

when it met in Liverpool in 1896. Joseph

Lister’s nephew, Arthur Hugh Lister became a medical student at Aberdeen,

graduating MB CM in 1895 and subsequently serving as one of Ogston’s

dressers. Dr John Scott Riddell,

one-time senior surgeon at ARI has suggested that Arthur Hugh Lister came to

Aberdeen at the suggestion of his uncle because of Alexander Ogston’s presence

there. Arthur Hugh Lister died at sea in

1916, during WW1.

Alexander

Ogston and military surgery

The

Franco-Prussian war lasted from July 1870 to May 1871. The belligerents were France, led by Napoleon

III, and the North German Confederation led by Prussia, whose chancellor and

prime minister was Count Otto von Bismarck.

War was declared by Napoleon III.

He had been led to believe France would easily win such a conflict, but

this belief proved to be wildly inaccurate.

The Prussian army mobilised more quickly and rapidly defeated the French

leading to the siege and occupation of Paris, French capitulation and the

deposition of Napoleon III. Casualties

on both sides were large, but especially amongst the French troops. There were many wounded requiring treatment

in the two armies, and it was this war which led Alexander Ogston to become

interested in military surgery. With so

many injured soldiers in hospital it was an inevitable consequence that

hospital-acquired infections would become a significant problem and it was

certain that Lister’s techniques would be severely tested. Professor Richard von Volkmann, a leading

German surgeon (and earlier critic of Ogston), was so successful in applying

Lister’s methods that other doctors quickly attended his wards to see the

success of this new approach to the reduction of wound suppuration and its

associated mortality. Ogston published a

paper in the British Medical Journal in 1870 with the title “A method of

antiseptic treatment applicable to wounded soldiers in the present war”. It described a simple method of dressing

gunshot wounds using carbolic lotion and carbolized oil (carbolic acid

dissolved in olive oil). Although the UK

was not a combatant in the war, humanitarian considerations led British

volunteers to become involved in aiding the wounded on both sides, for example

by manning ambulance parties to recover injured soldiers from the

battlefield. This was a development that

Alexander Ogston later encouraged in Aberdeen with his support of local

ambulance volunteers. It also led to

Alex Ogston introducing military surgery into his lectures to students in the

medical school, since a significant proportion of the medical graduates would

end up working in the army. But Ogston

also realised that in order to teach the subject effectively he needed to have

first-hand experience. He wrote in his

book, “Reminiscences of Three Campaigns”, “… it was incumbent upon me as a

teacher of surgery and professor in the University, to give instruction to

students in the subject of military surgery, and I was not long in finding out

that to impart a knowledge of it as applied to war it was indispensable for me

to witness its operations in the field.

Hence, when the opportunity arrived, I was drawn by degrees into the

experiences I am about to relate”. His

opportunity would arise during actions in the Sudan during the Egyptian

Expedition of 1884 - 1885 to relieve General Gordon, who had been besieged by

the Mahdi’s forces in Khartoum.

The Aberdeen

smallpox epidemic of 1871 - 1872

Several waves

of smallpox affected Aberdeen during the 1870s.

In December 1871, the first of these crises was upon the city. Because the disease was so infectious and

with significant associated mortality, the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary could not

treat the victims, forcing the Town Council, under the Public Health (Scotland)

Act 1867, to open a temporary facility at Mounthooly, which had formerly

accommodated the Bon-Accord Chemical Light Company, and which was exclusively

for the isolation and treatment of smallpox cases. Alexander Ogston, then Joint Medical Officer

of Health for Aberdeen, was put in charge of this hospital at the beginning of

January 1872. The epidemic was quickly

brought under control and by the middle of July 1872, only two patients were

being accommodated and no new patient had been admitted during the previous

three weeks. There had been 230 cases

with 37 deaths, a good ratio in relation to what had been achieved in other

towns. Alex Ogston, along with his

medical resident, Dr James Inglis, had clearly performed their roles skilfully

and conscientiously. Arrangements were

made to close the facility and Alex Ogston then submitted his bill for

providing treatment to 220 patients - £472, calculated at 2gns per patient. When this account landed at the Town House it

caused deep disquiet due to its size, though one councillor, Baillie Ross, “thought

the bill reasonable given that Dr Ogston’s private practice has been injured,

the sacrifice of home and family comforts”.

The first reaction of the Town Council was to claim they had no

liability to meet his bill at all, since his letter of appointment stipulated

that he would only get his normal salary.

However, when the emergency was over, they would consider if they should

pay him something extra. Ogston shot

back that the two were not related. The

bill for services at the Smallpox hospital related only to his appointment in

January in charge of smallpox. He

immediately asked to be relieved of his responsibilities at the smallpox

hospital and as Joint Medical Officer of Health, told them that he would not

forgo his claim and reserved his position.

In fact, both Alex and his father resigned almost simultaneously by

letter, Francis on 23 August and his son a day later. Alex Ogston clearly possessed a very

different personality from his compliant, financially indifferent and

accommodating father, with whom the Town Council was used to dealing. By some means an agreement was reached that

Alex Ogston’s bill for services at the smallpox hospital would be submitted to

the arbitration of Dr Alexander Kilgour, a highly respected Aberdeen doctor,

who had been Senior Physician at ARI, had an extensive general practice in the

city and had been involved in examining the living conditions of the poor in

relation to disease. Dr Kilgour

attempted a compromise, though the basis of his decision was unclear. Alexander Ogston would be awarded £230, less

than 50% of his claim. Dr Kilgour,

perhaps trying to be even-handed, criticised the Council for not specifying

Alex Ogston’s duties and Ogston for not obtaining a binding statement as to his

level of remuneration. When the Town Council considered the letters of

resignation, the Lord Provost, William Leslie made a pointed distinction

between the two Ogstons. “I have no

hesitation whatever in recommending acceptance of Dr Alexander Ogston’s

resignation, but I think we should hesitate before we accept Dr Francis

Ogston’s. Dr F Ogston has always shown

himself, under ticklish circumstances, to be conciliatory and very willing to

do all that devolves upon him. (Applause)”.

Indeed, Francis Ogston had offered to continue in post until a

replacement was found. The local

authority then laid down their plan for the future. The replacement medical officer was to be a

single post, not split and to be offered to Dr Francis Ogston at a remuneration

of 100gns per year. It was also

suggested that, if there were to be another epidemic, the medical officer

should be paid at the rate of 1gn per day.

Francis Ogston accepted the offer, in his characteristic style, without

demur.

Alexander

Ogston’s status grows

In November

1872, Alexander Ogston was elected a Fellow of the Medical Society of London

and a year later he was nominated as an examiner in Medicine at Aberdeen

University. Also, in the same year he

was appointed to a small committee of the University to examine the medical

curriculum. Two years after, Alex Ogston

was asked to join the Committee on the Act and Ordinances and on the Arts

Curriculum set up by the General Council of Aberdeen University to report on

subjects to be brought before the then imminent Royal Commission. The year 1874

saw Alex Ogston promoted to the position of Third Surgeon at Aberdeen Royal

Infirmary, a full surgical post which involved him actually performing

operations and being paid for so doing.

He was now 30 and his colleague, Dr JC Ogilvie Will stepped up in his

place as Junior Surgeon. Alex Ogston

then started to teach Clinical Surgery courses to medical students along with

the other two paid surgeons, Drs Pirrie and Kerr. Alexander Ogston’s rise up the surgical

hierarchy at ARI soon ascended another rung.

He was promoted to Second Surgeon in 1876, when Dr Kerr resigned, this

advancement being met with applause in the special court of hospital

managers. Dr Ogilvie Will then rose, in

lockstep, to Third Surgeon.

Interestingly, Sheriff John Dove Wilson, a leading barrister, judge and

legal author, who was one of the managers, proposed that a senior surgeonship

at the hospital should always be held by the Professor of Surgery in the

University, perhaps anticipating that ARI’s new second surgeon had further to

go and realising that it would be anomalous if there were to be such a

disconnect between the hospital and the medical school.

In the

operating theatre, Alex Ogston’s creativity was at work inventing new surgical

procedures. In 1877 he published a paper

on the surgical treatment of knock-knee, his operation being used widely until

it was in turn superseded by a technique invented by Dr Macewen of

Glasgow. Dr Ogston also lectured, in

German, on his new technique in Berlin under the title, “Zur operative

Behandlung von Genu-Valgum”. (For the

surgical treatment of knock-knees).

Alexander

Ogston’s proposed reform of medical societies in the North-East of Scotland

In 1885,

towards the end of his year as president of the local branch of the BMA,

Alexander Ogston delivered an address to the association at its annual

meeting. The text of this substantial

presentation has survived and illustrates many features of its author’s

personality. He had a substantial grasp

of history, especially of the medical profession and its doings in, or for, the

North-East of Scotland, he was an excellent writer and raconteur, with a

flowing style and a wide vocabulary, he was fluent in German, he revealed a

reforming zeal for whatever subject, or organisation, with which he became

associated, a belief in medicine being underpinned by science and he displayed

a high level of integrity, with a desire to enhance the general good. But his address also illuminated the reasons

for initiating the local branch of the BMA some 13 years previously, in 1872. Some extracts from Ogston’s speech will

illustrate these points.

“After

acknowledging the honour which had been done to him and stating that it would

be his aim to serve the Society so it should be rendered more useful during his

term of office and in such a way that no one would justly desire he had not

been elected”.

“As the tides

and waves of worlds come and go and the destinies of races and nations ebb and

flow in seeming consonance with the universal laws of change, so do phases of

change pass over bodies of men, leaving their marks to be read as lessons by

those who succeed, if they have the will and penetration to understand

them”. This is almost poetic and the

internal rhymes (“come and go”, “ebb and flow”; “bodies of men”, “understand

them”) surely deliberate.

“The Annals of

Aberdeen show that it has contained, not one, but many pioneers of knowledge

who have won among the teachers of Britain and the Continent a high and noble

name; that its sons of medicine have been physicians to potentates and kings;

and even in our own hour we could point to those who are doing the like, and

whom after generations will delight to honour.

The shelves of our libraries and the portraits in our halls tell us also

of many who, remaining in the midst of us, have by their labours and genius

gained for themselves a lustre that has not yet faded”.

“But I would

not willingly be taken for a laudator of only the times that are past and

played out – my purpose is far otherwise.

I would rather seize the opportunity which I have in addressing you to

point out that we who belong to the profession here, who are now in this room,

are acting unworthily to ourselves, are neglecting an opportunity of

benefitting and ennobling our profession, and are so using the short time at

our disposal that our successors of the next fifty perhaps even twenty

years or maybe less, will, unless we are

wise, pass their verdict on our living and acting as having been

unworthy”.

This last

statement was a preface to a complaint about torpor, lack of vision and promotion

of self-interest in the medical profession in Aberdeen over the previous couple

of decades, including within the Aberdeen Medico-Chirurgical Society, which

Alex Ogston had perceived and countered.

“It has always

been the reproach of our profession that it has been disunited and torn by

strife, and to some extent the reproach is true and especially it has been true

of the profession in Aberdeen during the twenty years that are gone (ie 1865

– 1885). Twenty years ago, the

profession here consisted almost entirely of middle-aged or elderly men. I can hardly remember one who was under

fifty, and a singular mixture of most dissimilar elements they were. Some of them were men of all nobility,

nobility in its various styles – some were outspoken, fearless men, as true as

the light of the sun and as penetrating, who, regardless of intrigues and

jealousies around them, walked their own unassisted way as the acknowledged

leaders of the profession – others were of less force and more gentleness, who

strove to do what was right and just, but seeking to evade the turmoil of life,

passed through it little noticed in the privacy of their lives – and in

contrast with them is the meteor-like course of others, great yet little, noble

and generous at times, narrow and unjust at others, who, with powers that

should have raised them high and helped their brethren higher, yet fell short

of the goal they should have won, and failed too frequently and too lamentably

where they ought to have been pioneers to their colleagues and brethren. Besides these there were the usual grades of

mixed good and bad, the much bad with a little good, and the wholly bad when

weighed in the balance, not perhaps with other men, but with what they ought to

have been. As time passed on our best

lights went out, and the profession in Aberdeen fell to what I must call a very

low ebb. Its reputed leaders were men

without diameter, or without proper proportion in their diameters. Small or narrow, all were actuated by no

great thoughts for the welfare of the profession; and, starving under their

cold shade, science ceased to hold up its head in our midst. Our one local Medico-Chirurgical Society, the

pantheon of physic in Aberdeen, dwindled down to the verge of extinction, the

two or three who attended its meetings finding no justification for their doing

so in the thin and even injurious pabulum there provided for their intellects,

and everywhere mutual distrust and malevolence were rife among those who should

have been co-workers and friends”.

The oldest

medical society for doctors in the North-East of Scotland in the 1870s was the

Aberdeen Medico-Chirurgical Society, founded in 1789 by Aberdeen medical

students unhappy with the quality of medical teaching at both King’s and

Marischal colleges, as the Aberdeen Medical Society. One of the student founders of the Aberdeen

Medical Society was James McGrigor, who would later achieve considerable

prominence in military medicine. In

1811, the Aberdeen Medical Society evolved into a postgraduate organisation. This medical club acquired a home in the form

of the grand Medical Hall, designed by architect Archibald Simpson in a

classical style, in King Street, which was opened in 1820. By 1844, the society had changed its name to

the Aberdeen Medico-Chirurgical Society, an appellation which survives to this

day. The “Med-Chi” was followed in 1865

by the North of Scotland Medical Association, a conglomeration of all the

medical societies in the North-East of Scotland, including the “Med-Chi”. The purpose of this new grouping was “to

promote friendly intercourse among the members, the discussion of questions of

general or scientific interest to the profession and giving expression to the

opinion of the profession in this part of the country on public questions”. Individual membership was also possible.

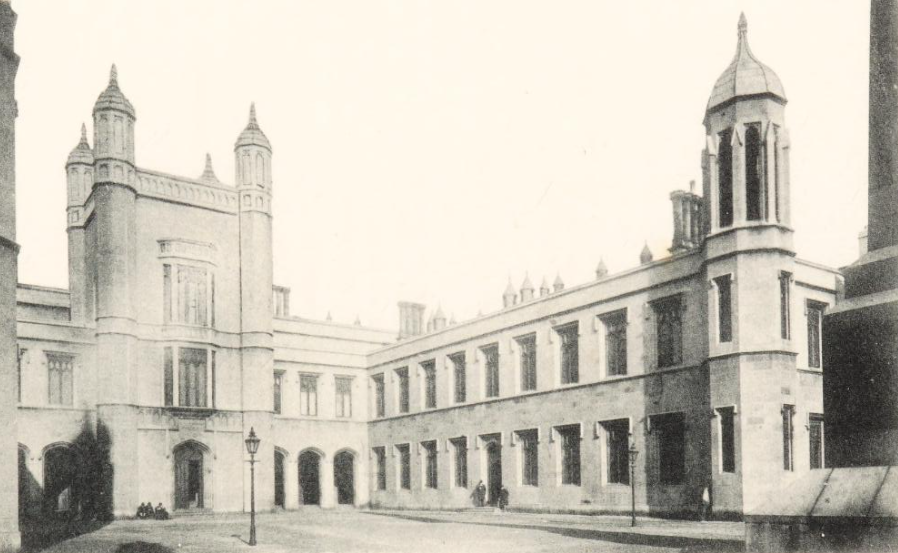

Medical Hall, King Street, Aberdeen

The

Ogstons gravitated to the North of Scotland Medical Association, following

their disillusionment with the Med-Chi but also found that organisation

underwhelming. The amenable Francis

Ogston (1803) served during 1871 as president of that association. His

son. Alex was less accommodating as explained in his 1885 talk, “It was a

heart-breaking time for Aberdeen science.

Our North of Scotland Association, designed and fitted though it was to

unite the profession of the district in name and in reality, fell upon evil

times when it was originated, and has, during the whole course of its

existence, from one unfortunate cause or another, never done anything that

could be considered a good reason for continuing to be”. Alex Ogston then turned his attention to a

solution for this lack of purposeful interaction in the medical community.

“Amidst the

existing chaos of those days a few of the younger men were impelled together to

an effort to remedy the existing evils.

They resolved to set their face up against the dishonourable

professional courses then so general, and against those who were known to

practice them, and to endeavour to stimulate the decaying scientific aspect of

Aberdeen medicine into a renewed vigour more in keeping with what it had once

been, and ought to be”.

There was

another club for doctors, the Aberdeen Medical Club which operated between at

least 1868, but probably earlier, and 1875.

At its meetings members would make presentations on interesting cases or

conditions that they had come across but disharmony intervened and, due to

differences in "vital and fundamental doctrine" between members, the

club was disbanded in 1868. A small

group of doctors, including Smith, Ogston, Fraser and Davidson, continued to

meet but the gathering proved to be inviable and the club finally ceased in

1875.

Dissatisfaction

with the Med-Chi came to a head for the Ogstons in 1872. Even before this year, at the 1869 AGM of

that organisation, neither Ogston was involved in the management of the society

for the following year. An ordinary

meeting of the Med-Chi was held in February 1872, immediately followed by a

special meeting “to consider and determine on the proposed alterations in the

situation and arrangements of the Society”.

No report of that special meeting has been uncovered, but it seems

likely that this was the occasion when Alex Ogston and his associates, the

angry young men of the Aberdeen medical community, sought change in the Med-Chi

but failed in that quest. One bone of

contention was the exclusion of country doctors from the Med-Chi. Alex Ogston was 28 at the time and his

solution to the problem of the thin gruel of medical discourse was to establish