The origin

of the Ogstons

“Ogston” is a

rare (8,518th most frequent) and highly localised locative or

toponymic (one derived from a placename) surname. At the 1881 GB Census, 286 of the 367 individuals

recorded bearing that name lived in Aberdeenshire. Others lived in nearby counties, 17 in

Kincardineshire, 11 in Banff and 5 in Moray.

Additionally, another 10 individuals were recorded with the surname

“Ogsten”, all living in Moray. This variant is possibly a machine mis-transcription

of Ogston. The derivation of “Ogston”

is probably as a corruption of “Ogg’s Town” and there is circumstantial

evidence to support that idea. The

surname “Ogg”, though rather more frequent than “Ogston”, is also found at its

highest concentration in the North-East counties of Scotland. Nairn 102/10^5, Moray 75/10^5, Banff 134/10^5,

Aberdeen 121/10^5, Kincardine 62/10^5 and Angus 43/10^5. Further, there was a parish of Ogston in

Moray which was abolished through its merger with the adjacent parish of Kinnedar

in 1642. The new parish was called Drainy

and contained the now well-known settlement of Lossiemouth. Genealogical work by various members of the

Ogston lineage (essentially what would now be called a “one surname” study)

traced the occurrence of Ogston (and its variants such as “Hogeston”, “Auxton”

and “Ogiston”) in the North-Eastern counties back to the start of the 12th

century. This is about the time of the

origin of surnames. However, a direct

lineage from the present back to the 13th century has not been

established, though there can be little doubt that all the Ogstons recorded in

Aberdeenshire and nearby counties are related to each other. About the beginning of the 13th

century, the Ogiston family was seated in the lands of Hogeston in Morayshire. Much mention will elsewhere be made of the

involvement of the Ogstons with the University of Aberdeen, which was formed in

1860 by the merger of two separate institutions, King’s College, established in

1495, and Marischal College, dating from 1593.

The chapel at King’s College was built between 1498 and 1509 and at

least some of its oak seating dates back to about 1509. It was the tradition for early King’s College

students to carve their names into the woodwork in the chapel and the oldest

dated name there is that of “J Ogston 1582”.

This is a most graphic illustration of the antiquity of the link between

the Ogstons, the city and county of Aberdeen and the local universities.

Flax and

thread

The lineage of

Ogstons, which the present series of papers follows, can be traced back with confidence

to William Auxton, born in 1706. His

wife was Elizabeth Ritchie and the couple’s first child, named Alexander, entered

the world in 1734 at Pitsligo, Aberdeenshire, a parish located about four miles

from Fraserburgh in the north-east of the county. William subsequently became the schoolmaster

at Tarves, located 16 miles north of Aberdeen. He died at Tarves in 1774. Alexander Ogston (1734) married Isabel Lind

and the couple’s first child, Alexander (1766) proved to be highly significant

for the subsequent success and prominence of this Ogston line. He is thought to have migrated to Aberdeen

city about 1785, aged 19, where he started a business as a lint and thread

dealer, though a search of the Aberdeen Journal between 1785 and 1801 did not

uncover any citations of his activities.

Lint and thread are derived from flax, which was widely grown during the

18th century in Aberdeenshire.

It is unclear if Alexander Ogston (1766) was involved in the production

of fibres from flax stems, a multistage process called flax dressing, requiring

much skill on the part of the operative.

The immediate product, lint, is a fluffy, random arrangement of flax

fibres, which can then be spun into thread for the manufacture of various

grades of fine to coarse cloth. Aberdeen

had several significant flax weavers after 1750 and Alexander Ogston (1734) may

simply have been an intermediary between the producers and the spinners and

weavers, or he may himself have been a flax spinner. From about 1820, flax cultivation in

Aberdeenshire declined due to competition from imported cotton and a preference

for imported flax, where this fibre was still employed, from Continental

Europe.

Candles

The first

indication of a diversification of Alexander Ogston (1766)’s lint and thread business

came in an announcement in the Aberdeen Journal of 17 November 1802. “Candlemaking. Alexander Ogston, dealer in lint and thread

in Aberdeen begs leave to acquaint his friends and the public that he has

lately engaged an experienced candlemaker and commenced business in that line

at his manufactory on the Lochside. He

has now on hand a large quantity of well-made candles which he can confidently

recommend and will sell on reasonable terms.

An apprentice wanted to the candlemaking business”. This advertisement was repeated on 24

November and 1 December of the same year.

Ten months later a further advertisement was made in the Aberdeen

Journal. “Alexander Ogston, Lochside,

Aberdeen. Begs leave to return thanks

for past favours in the candle line and has now on hand a large quantity of

spring-made candles, dipt and moulded which he can with confidence recommend to

his friends and the public and will sell on reasonable terms. Continues to deal in thread and lint as

formerly”. Candles were already being

produced by the two main production methods, and the qualification “spring-made”

may refer to tallow, then the main raw material for candle manufacture, being

rendered from the fat of animals which were slaughtered at a time of year when

they had more nutritious feed.

At the earliest

stage of his chandlery business, Alex Ogston (1766) seems to have sold directly

to the public. However, as production

ramped up, the firm moved to trading exclusively on a wholesale basis, with

local grocers retailing Ogston’s candles to the general population. The reason for moving to wholesaling of

candles was probably dictated by the progress made in mechanising the manufacturing

process and the resultant upscaling of production. In 1828, in the aftermath of a fire at the

works, A Ogston (1766) advertised for sale “Damaged candle and tallow. To be sold by public roup at Mr Ogston’s

Candle Works Lochside for behoof of the insurers. About 10 to 12 cwt dipt candles partially

damaged in the late fire there. Also,

about 8cwt melted tallow affected merely in colour and as fit for soap-making

as ever”. This announcement gives some

indication of the scale of production of candles by this year. However, the mention of tallow “fit for

soap-making” probably reflects the commonality of raw materials between candle-

and soap-making and does not show that Ogstons were themselves manufacturing

soap at this time. That change came much

later, in 1853.

The

chemistry of candles and soap

Before

considering the further development of the business started by Alexander Ogston

(1766), it may be helpful to the reader to make a diversion into the processes

involved in both candle- and soap-making and the market conditions for both

types of product in Aberdeen and its environs, post-1750.

Tallow is released

from the fatty parts of animals, typically cows and sheep, by boiling to

separate the fat as a floating component, which can be collected largely free

from the other tissue constituents, mainly proteins and water. Animal fats vary in composition but

essentially consist of triglycerides formed between one glycerol (glycerine)

molecule and three fatty acid molecules, the most frequent of which are

stearic, palmitic and oleic acids.

Tallow can be used directly in the manufacture of candles, but it burns

with a smoky flame and emits an unpleasant smell. Candles made from tallow are thus the

cheapest. Tallow can also be used to

manufacture soaps. This is achieved by

hydrolysing the fat molecules with either sodium hydroxide or potassium

hydroxide to produce glycerol (glycerine) and a mixture of soaps, which are

salts of the fatty acids. Sodium

hydroxide generates hard soaps, while potassium hydroxide produces soft

soaps. Candles can also be produced from

long chain saturated hydrocarbons with the general formula Cn H(2n+2). Such hydrocarbons can be sourced from

beeswax, whale oil or paraffin wax, which is produced in the distillation of

crude oil. Plant oils, such as palm oil,

can also be used as raw material for both candle and soap manufacture. Local sources of alkali in Scotland were wood

ash and the ash produced by kelp burning, mainly generating potassium

hydroxide.

Candle and

soap manufacture in Aberdeen after 1750

A search of the

Aberdeen Journal in the decades after 1750 reveals many references to

manufacturers of soap, candles or both products in central Aberdeen. Most of these producers were small-scale and

their businesses were often ephemeral. For

example, in 1750, “Arthur Bradley soap boiler and candlemaker at John Lumsden’s

Watchmaker, Exchequer Row, Aberdeen has now erected a factory for making

candles”. No further reference to Arthur

Bradley has been found. In 1767, Robert

Duncan announced that he “continues to make tallow candles of all sorts at his

house in the Gallowgate”. Duncan appears

to have been reasonably successful as in 1781 he sent a relative, Alexander

Duncan, to Banff to manufacture candles there.

By 1783 Robert Duncan could announce a further significant business

development. “Robert Duncan and Sons

have engaged Mr John Dent late soft soap maker in London. Under his directions they have now completed

a new soft soap house and now have soft soap ready for sale. They also continue to manufacture all kinds

of yellow and hard soap and dipped and moulded candles. These articles may be had at their

manufactory in the middle of Gallowgate”.

Sadly, this expansion came to nought as the same year it was announced

that “Robert Duncan & Son soap and candlemakers in Aberdeen (have made)

arrangements with creditors”.

Ex-employees of defunct businesses would often set up in business themselves. In 1798 the Aberdeen Journal contained the news that “Copland and Milne have resolved to give up their candle-making business within a short time”. As a consequence, “John Bothwell Upperkirkgate Aberdeen left the house of Messrs Copland and Milne to set up on his own account. Has a complete assortment of spring-made candles which he is selling off at 13s 6d per stone credit and 13s ready money, moulded at 14s 6d per stone credit and 14s ready money, Dutch weight”. Another ex-employee of Copland and Milne also branched out on his own account. “James Laing who has been 9 years in the house of Copland and Milne begs leave to acquaint the public that he has commenced business on his own account in the house lately possessed by Mr Shinnie, Flourmill Brae. Will produce candles of all sorts”. Copland and Milne soon resumed the manufacture of candles, in 1801, this time in partnership with their former employee, James Laing. Initially the firm was located in Flourmill Brae (Mr Shinnie’s former premises) but subsequently moved to Shiprow, where they kept a “large mastiff dog”, presumably to deter thieves. Finally, in 1813, the firm moved again, this time to Loch Street, where it continued trading until bankruptcy intervened in 1827.

The Napoleonic

War extended from 1803 to 1815 during which Napoleon Bonaparte introduced a

trade block between his continental allies and the UK. Between 1802 and 1806 there was a substantial

drop from 55% to 25% in trade with the Continent. This must have had some impact on the import

of raw materials, soap and candles and may have stimulated British producers to

find home sources. Another impediment to

candle manufacture was the tax on candles which had been introduced in

1709. It led to widespread tax dodging

by small local manufacturers, and the Commissioners of Excise, in response,

imposed heavy fines for possession of home-made candles or for the possession

of soap-making implements. The tax was

eventually abolished in 1831. Similarly,

soap manufacture was taxed between 1712 and 1853.

Alexander

Ogston (1766) and his son, Alexander Ogston (1799)

Alexander

Ogston (1766) married Helen Milne in 1796 at Fyvie, Aberdeenshire. The couple had five children, Sarah (1798),

Alexander (1799), George 1801, Francis (1803) and Helen (1813). Alexander (1799) was marked out by his father

as being the one to become associated with the candle-making business and was

its eventual inheritor. From 1824, when

he would have been 25 years old, Alexander (1799) had an entry in the Scottish

Post Office Directory for Aberdeen, which described him as a Tallow-chandler,

probably indicating the year in which he became a partner in the firm with his

father. This co-partnery of father and

son continued until 1830, when the following notice appeared in the Aberdeen

Journal of 29 September, announcing the exit of Alexander Ogston (1766) from

the firm. “Alex Ogston, tallow chandler,

having in June last resigned business wholly in favour of his son, Alexander,

begs to return his best thanks to his friends for the warm support which they

have afforded him for a period of 45 years (ie from1785 when he would have

been 19, though he was only a candlemaker from 1802) and now solicits that

the same steady patronage be continued to his son who carries on the concern in

the same premises as formerly for his own behoof. With reference to the above notice, Alexander

Ogston junior (1799), in acknowledging the favours of his friends and

the public while in partnership with his father begs to assure them that the

same care and attention shall be bestowed as heretofore upon their orders of

which he respectfully solicits continuance.

His present stock of spring-made mould and dipt candles is extensive and

being manufactured of the best materials and under his own immediate

superintendence he can warrant them to give every satisfaction. All debts owing to the late firm are payable

to A O Jun by whom any claims against the concern will be discharged on being

presented. Aberdeen September 25, 1830”. Subsequently, Alexander Ogston (1766)

continued to have entries in local business directories, identifying him as a

Tallow-chandler of 52 Loch Street, the same work address as his son, until 1833,

after which he was described as “late Tallow-chandler”.

The subsequent

life stories of Alexander Ogston (1799)’s siblings contain an interesting mix

of outcomes. Sarah Ogston (1798), the

eldest child, married David Gill (1796) in 1825, a partner, with John Farquhar,

in a firm of painters and glaziers, Farquhar & Gill, found near to the

Lochside, where Alexander’s business was located. Farquhar & Gill became very successful

and later diversified into the manufacture of paints and varnishes. The eldest child of Sarah Ogston and David

Gill was endowed with the given names “Alexander” and “Ogston” after his

maternal grandfather, and AO Gill took charge of one new firm when the original

entity split into two, with James Farquhar (son of John) continuing as a

plumber and brazier and AO Gill concentrating on designing and manufacturing

paint. In 1880, Alexander Ogston Gill

led his firm to extensive new premises for paint manufacture, which became

known as the North of Scotland Colour Works, located in Drum’s Lane. This firm had remarkable longevity,

continuing trading into the 1970s.

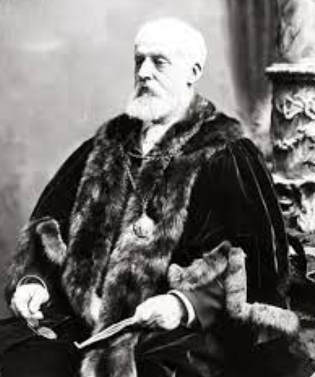

Alexander Ogston Gill, a very active member of commercial and civic

society in Aberdeen will reappear in this series of stories about the Ogston

clan.

Farquhar & Gill's Colour Shop

George Ogston (1801), the third child of Alexander Ogston (1766), did not succeed in life, though little is known of his activities other than that he emigrated to Australia. He had borrowed money from his father, became insolvent, was unable to repay his parental debt and was almost completely excluded from the benefits of his father’s will. “George has already received his share of patrimony and has discharged his legal rights, yet I am disposed to provide for the event of his circumstances being reduced, therefore if my executors shall see him in destitution or in want of assistance they are hereby empowered to pay to him for his alimentary use during his life the dividends of the said 90 Gas shares or £20 per annum in lieu thereof at their option”.

Helen Ogston

(1813), Alexander Ogston (1766)’s youngest child, also made a good marriage, to

a Londoner, William Reid, a ship and insurance broker, who became the manager

of the Aberdeen Ship Insurance Company.

Francis Ogston

(1803) was, without doubt, the intellectual of the family and the individual

who, though not lacking in commercial acumen, sought his career in the practice

of medicine, rather than as a merchant or a manufacturer. An extensive account of the life of Francis

Ogston (1803) and of his sons, Alexander (1844) and Francis (1846), all

prominent medical men, will be given elsewhere.

But how did Francis become involved in medicine, rather than seeking his

career exercising the traditional, commercial bent of the family? The answer probably lies in the location of

the family homes and the family business.

The location

of the Ogston business and Ogston family houses

Although Alexander Ogston (1766) had arrived in Aberdeen in 1785, no definite information has been found concerning the location of his business until 1802, or of his home until 1807. Between 1802 and 1822, the Ogston manufactory was said to be in, or at, Lochside. This is a reference to the artificial loch, fed by an aquaduct from the Denburn and by other water sources, which was located in the area to the NW of Marischal College now occupied by Loch Street and the adjacent land to the west. The loch, in Medieval times, was the main source of water for town residents but it became over-exploited and polluted. It shrank progressively and by 1838 it had completely dried up, the land it once occupied being developed for other purposes and the sinuous shape of the loch in a plan of 1828 now being reflected in the course of Loch Street. The location of the Ogston manufactory at Lochside may well have been in order to obtain a ready supply of water for the processes employed and the name may reflect the situation before the development of the thoroughfare of Loch Street.

In 1807 and 1808, “Mr Ogston”, probably Alexander Ogston (1766), was living in Frederick Street adjacent to “three genteel lodgings” which were then newly built, though it is unclear if he was renting his house, or if it was in his ownership. This dwelling lay about 1/3 mile from the Ogston manufactory. In 1811, a Mr Ogston was living in North Street, probably a little nearer to the Ogson works, in a house “belonging” to him. However, by 1824, the family home of Alexander Ogston (1766) was definitely located in 2 Gallowgate, close to the northern end of Marischal College, the university located in the New Town. The date of first occupation of 2 Gallowgate can thus be tentatively placed between 1811 and 1824 and the Ogstons lived at this location until 1832. The domestic arrangements of the Ogston family and the office address of the manufactory underwent several changes in the period 1833 – 1842, in part brought about by family deaths and marriages. For a short period about 1833, the home of Alexander Ogston (1766) and his family became 54 Lochside before changing again in 1834 to Ogston’s Court, 84 Broad Street for Alexander (1766) and his son Francis (1803). (Broad Street runs along the western side of Marischal College and Gallowgate is a northwards continuation of Broad Street, the boundary between the two being placed at the northern extremity of Marischal College). The elder son, Alexander (1799), set up home in a different property, 56 Lochside. This was the year of his marriage, so it is not surprising that he would wish to occupy different premises from his parents and siblings. Alexander (1799) moved house again the following year,1835, to the house next door, 56 Lochside. He probably remained there until the death of his father in 1838 (though the name of the property changed to 56 Loch Street), when he moved his home to the Ardoe estate, located about 5 miles from the manufactory at Banchory-Devenick, close to the south bank of the river Dee. Helen Milne, the widow of Alexander Ogston (1799) continued to live at Ogston’s Court until her death in 1842. Francis Ogston (1803) also remained at Ogston’s Court. He married in 1841 (at Ardoe) and the house in Ogston’s Court became his family home until 1844. Francis Ogston, who was born in 1803, had lived adjacent to Marischal College as a youth and must have been familiar with the University and its activities, including gowned academics and noisy students, from daily observation. One of the main academic occupants of Marischal College was the Medical Faculty. An Arts curriculum was also taught at Marischal. It is not a surprise to find that the intelligent Francis should aspire to become a Marischal College undergraduate himself. The biographies of Francis Ogston (1803) and his two medical sons, Alexander (1844) and Francis junior (1846) will be dealt with elsewhere.

There are several traditional Scottish architectural terms which require explanation. A “court” consisted of buildings, often houses, on both sides of an access perpendicular to a main road. Its access was narrow and suitable only for pedestrian movements. In contrast a “wynd” had an access wide enough for a horse and cart. A “close” was a gated community without open access. Closes and courts were often entered via a pend (as in the case of Ogston’s Court), a covered passageway through a building sited on the street. Closes, wynds and courts were typically named after the owner. The name “Ogston’s Court” and the fact that this name is incised in the stonework over the pend, likely from the date of construction, suggests that it was probably built, or at least owned, by someone with the surname “Ogston”. Reference to historical plans of Aberdeen puts the date of its construction between 1746, when it was not present, and 1773 when it could be clearly recognised adjacent to the quadrangle of Marischal College, on the College’s northern border. If this interval is valid, construction and initial ownership of Ogston’s Court could not have been due to Alexander Ogston (1766), though “my dwelling house in Broad Street (ie 84 Broad Street, Ogston’s Court) where we now live in family together” was in his ownership in 1838, the year of his death. Could that role have been fulfilled by a relative, perhaps his father, Alexander (1734)?

Both the will

and the inventory of personal possessions of Alexander Ogston (1766) are

available for consultation. At the time

of his death in 1838 he had acquired considerable wealth, though it is unclear if

any assets were derived from an inheritance as opposed to being generated by

his own commercial activities, principally manufacturing candles. The total value of his personal and moveable

estate was just over £6,046 (about £713,190 in 2021 money). Included in the list of assets were shares in

a number of significant companies, Aberdeen Gas Company, North of Scotland Assurance

Company and North of Scotland Banking Company

Additionally, he owned

significant real estate. The landed

property of Ardoe had just been acquired before his death (he died at Ardoe on

27 July 1838) and, in addition to the house at Ogston’s Court, 84 Broad Street,

and the house at 2 Gallowgate, he also owned “the tenement of houses … situated

between the Gallowgate and Loch Street of Aberdeen” and three let properties at

Lochside. In 1863, “The family house in

Ogston’s Court, Broad Street and the upper floor in Broad Street entering from

no 2 Gallowgate” were offered for let and were still in the ownership of the

Ogston family.

From 1824, the

address of the manufactory changed many times and reference to the Scottish

Post Office Directory for Aberdeen allows those movements to be traced. In that year the address of A Ogston’s Works

(possibly the office postal address) was given as 52 Loch Street and remained

so until 1832, when it changed for one year to 53 Loch Street. Subsequent alterations were as follows. 1833, 53 Loch Street; 1834 – 1839, 55 Loch

Street; 1840, 86 Loch Street; 1841 – 1846, 88 Loch Street, 1847 – 1849, 86 and

88 Loch Street; 1850 – 1855, 86 Loch Street, 1856 – 1862, 84 and 86 Loch

Street; 1863 – 1869, 92 Loch Street. The

fundamental significance of this transformation is likely to have been the

almost constant development and expansion of the candle and (from 1853) soap

works as new buildings were constructed, old buildings re-purposed, and

additional properties acquired. The Works

evolved throughout the 19th century within a block of land bordered

by Loch Street in the west and Gallowgate in the east. Some of the properties used by Alexander

Ogston (1799) for his own domestic accommodation (54 and 56 Loch Street) were

adjacent to buildings used on occasion as the firm’s office address (52, 53, 55

Loch Street). During the 1830s,

Alexander (1799), in effect, lived at his place of work. Similarly, in the late 1840s and early 1850s,

he used other Loch Street properties (86 and 88 Loch Street) as domestic

accommodation in the city while his main home was at Ardoe. Both numbers 86 and 88 were used as company

accommodation from time to time, occasionally simultaneously with domestic uses. In 1849, no. 86 Loch Street was described as

Ogston’s warehouse where retailers could make their enquiries. In 1863 it became surplus to the firm’s

requirements and was advertised for let.

“The situation is well adapted for carrying on a wholesale or

manufacturing business and if wanted considerable accommodation can be got

behind”. After 1863, the office address

of the firm changed to 92 Loch Street and remained so until 1922.

Between 1824 and 1853, when the tax on soap was abolished and soap manufacture was added to the other activities at the Ogston factory, there were other indications of the growth and expansion of the Works. The first identified export of candles was to Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1839 when 28 boxes were despatched. Further consignments followed to the same destination in 1839 (25 boxes), 1840 (61 boxes). Other Aberdeen manufacturers were exporting to the same destination, too. Ogstons were also notably successful in supplying the needs of local institutions, such as the hospitals, the prison and the harbour board, who tendered their requirements annually for tallow and candles. By 1850, Ogstons had started importing tallow from Hamburg.

The

relationship with the Price Candle Company

Eighteen

forty-five saw a significant development for Alexander Ogston (1766)’s candle

business when the firm became agents in the North of Scotland for Edward Price

& Co, London, then and still today the most important candle manufacturer

in Britain. Price established a factory

at Belmont, Vauxhall and “Belmont” was used as a trademark to distinguish their

products. The company, since 1847 called

“Price’s Patent Candle Company”, had been established in 1830 by William Wilson

and Benjamin Lancaster. It developed

technology for manufacturing stearine, the triglyceride of stearic acid, from

coconut oil. Stearine, a fat, has a high

melting temperature and is thus ideal for the manufacture of candles, which are

called composite candles. They are

odourless when burning and produce a bright light. Up to this time the best candles were made

from beeswax, but it was a much more expensive raw material than coconut oil. Composites were supplied to Queen Victoria

for her wedding to Prince Albert in 1840 and Price has held a Royal warrant ever

since. By 1849 the Belmont factory

employed 700 people and consumed 4,000 tons of vegetable oils each year. While retaining stocks of “Patent Belmont

Wax, Sperm and Composite Candles” to supply the local wholesale trade, Ogstons

also had an arrangement with Price for bulk orders (“not less than twelve

dozen”) for local customers to be dispatched direct from the Belmont factory. “Wax” referred to candles made from paraffin

wax and “sperm” to candles manufactured using the wax component of sperm whale

oil. Ogstons clearly saw this agency for

Price as being very important as they always stressed the linkage in their

advertising. It gave them access to

superior, if more expensive, products than the tallow candles that they

manufactured in Aberdeen. The following

advertisement appeared in the Aberdeen Journal in 1848. “The Patent Belmont Candles. The subscriber has this week received a full

supply of the above goods which comprehend – Belmont Wax, Belmont Sperm,

Belmont Stearine Sperm in 3lb boxes, Belmont Composite and Belmont Night

Mortars. These candles are strongly

recommended to the notice of customers possessing as they do all the essential

qualities of the best wax and sperm at about one third of the cost. They require no snuffling and in burning the

combustion is so perfect that the most delicate walls and furniture remain

unsullied while a purer atmosphere much more favourable to health and comfort

is insured than when gas or oil light is used.

Alex Ogston, Tallow-chandler.

Agent for Price’s Patent Candle Co in the North of Scotland. 86 Loch Street”. Price also supplied a variety of other

products through Ogstons, including “Wax and Composite Moons for carriage and

gig lamps”, “Patent Belmont Oil”, cocoa nut oil, Argand Oil and machinery

oil. By 1850 Ogstons were themselves

manufacturing “Albert Mortars and Child’s Night Light”, possibly by licensing

the processes from Price who were vigilant in the defence of their intellectual

property rights. Other products were also

supplied by Price, including black or coloured sealing wax for bottles and

parcels. In 1852, Price also supplied

the “Patent Distilled Palm Candle”, which Ogstons qualified as “not as good as

best composites but superior to any other on the market and much cheaper”.

Price's Belmont Candle Factory

Ogstons begin to manufacture soap

Alexander

Ogston (1799) announced the next major advance in his business, inevitably via

the Aberdeen Journal, in August 1853. “To

the trade. The subscriber begs to

acquaint his friends and the public that he has been making arrangements at his

works for the manufacture of hard and soft soaps and is now sending out the

latter sort in firkins (small barrel with a capacity of about 41 litres)

and half firkins. In the month of

September, he expects to be in a position to offer some of the kinds of hard

soap. Having spared no expense in

procuring a stock of good material and having engaged a maker of great

experience he trusts to be able to supply a first-class soap at the lowest

market rate. Alex Ogston Aberdeen 2d

August 1853”. As with every other

development made by the firm, it was planned, deliberate and backed with the

necessary human and financial capital.

In the 1854 edition of the Scottish Post Office Directory (text likely

submitted early in 1853), Alexander Ogston (1866) now described himself as "Tallow Chandler and Soap Maker" and by mid-1853 his

works were described as the “Soap and Candle Manufactory”. The first soap produced was soft soap, made

using potassium hydroxide as the saponifying agent. Hard soaps, made using sodium hydroxide,

followed in September 1855 with the following announcement in the press. “Hard and Soft Soaps. The subscriber begs to acquaint the trade

that having completed the erection of New Works for the production of Hard

Soaps he will now be able to supply both hard and soft in any quantity on the

best terms and of a quality equal to any in the market. Alexr Ogston.

Aberdeen Soap and Candle Manufactory, 86 Loch Street”. Diversification of soap products was

rapid. “The different sorts of soaps,

namely, White, Mottled, Pale Yellow and Soft can now be had at the subscriber’s

works of best quality and on the best terms”.

Significantly, the advertisement, which was repeated many times, added

that “The soaps all bear the maker’s stamp”.

In the coming years, this message would be pressed home relentlessly –

beware of inferior imitations!

Eighteen

fifty-five saw another development of great importance when Alexander Milne

Ogston (1836), the elder son of Alexander (1799), then aged 19, was taken into

the firm, though the significance of the event was likely recognised as such by

few observers at the time.

The

relationship between Ogstons and Price’s Patent Candle Company continued and,

with the latter increasing its manufacturing capacity, a price reduction was

offered to wholesalers by Ogstons in 1857.

The same advertisement also noted, “A supply of Belmont glycerine soap

made from Price’s pure glycerine is to hand.

This soap is much recommended for washing children and shaving,

etc. Softens the hands and prevents

chapping. Most agreeable toilet soap”. It appeared that Ogstons was now an agent for

Price’s soaps too. Glycerine, which has

hand-softening properties, was a by-product of the saponification of

triglycerides. Another innovative

product, Whitmore & Craddock’s University candles (manufactured by Price’s

Patent Candle Company) was offered by Ogstons to “Universities, the Clergy, the

Bar, Students, Schools and Reading Societies in General”. This relationship with the leading London

candle-maker may have brought the realisation to Alexander Ogston (1899) that

his own candle manufacturing had not advanced beyond the production of cheap,

basic tallow candles and that more diversity was necessary for further

advancement. That change appeared in

1861 with a major investment in new plant to produce candles with better

burning characteristics. “Subscriber

begs respectfully to acquaint his friends and the public that he has just

completed an extensive distilling apparatus on the most approved principles for

enabling him to bring out the various sorts of stearine and composite candles

of a quality at least equal to the best makers in the Kingdom. In future an ample supply of the various

sorts will be kept in stock and in soliciting the continuing support of his

friends the subscriber begs to assure them that it will be his study at all

times to produce first class goods on the most liberal terms. The stearine and composite candles will be

found to be an agreeable and economical light, require no snuffing and emit no

smoke while burning. The trade only

supplied. Alexander Ogston, The Aberdeen

Soap and Candle Works, 86 Loch Street”.

Stearine would have been distilled from a plant oil, most likely palm

oil, which would have been imported.

During the

mid-19th century there was a substantial whaling and sealing fleet

operating out of Scottish ports, principally in the north-east, where Peterhead

was the most important base. In 1859,

Alexander Ogston advertised “a quantity of new seal oil” for sale, which was likely

to have been sourced from the local fleet.

From time-to-time other new products, outside the soap and candle lines

were also offered.

Ogstons

continued to improve the soaps that they produced. Soft soap was used for household purposes but

often had bad odour. In 1862 Ogstons

advertised an improved version. “The

frequent inquiry for soft soap free from the objectionable smell of the

ordinary quality has induced the subscriber to manufacture a superior article

from the purer and sweeter oils. This quality

of soap being free from all unpleasant odour and possessed of great detergent

power is specially suitable for household purposes and for cleansing all

animals particularly horses, cows and dogs besides being beneficial to their

skins. It is also valuable for cleaning

plate, paint and all kinds of leather harness.

The packages which are firkins, half-firkins and 7lb tins bear the

maker’s name and will be supplied by any respectable grocer in town or country

and wholesale at the works”.

In 1862,

Ogstons advertised a wider range of sophisticated candles for sale which had

been manufactured locally. “Stearine,

Wax, Sperm and Composite Candles all entirely manufactured at the subscriber’s

works are strongly recommended to dealers and others. Will be found to be greatly superior to most

candles on the market”. This development

would have rendered redundant the agency agreement with the Price company. Although no definite date has been found for

the termination of the agreement, the last year that it was definitely in

operation was 1861. Interestingly, in

1875 Ogstons recruited a long-time employee of Price, Mr James Lee, to work for

them in Aberdeen. He must have walked

out of the Belmont works with a considerable amount of know-how in his head.

Trouble with

the neighbours

However, the

development of a major manufacturing facility, which generated obnoxious odours

and other nuisances, in a location closely surrounded by housing near the

centre of Aberdeen was bound to generate opposition. In 1861, residents “in and about Loch Street”

sent a memorial to the Aberdeen Police Commissioners complaining about Ogston’s

operations. It was written in lurid,

over-egged terms typical of NIMBYs everywhere and was considered by the

Nuisance Removal Committee. The

effusions from the works were said to be “not only most obnoxious to the smell

but we believe highly injurious to human life”.

The memorialists, 31 in number, went on to say, “in strongly emphasised

manuscript” that “at times the stench from this pest house is really unbearable

causing giddiness in the head, sickness at the stomach, pains and weakness of

the eyes and a sort of languid stupor over the whole body”. If this “terrible pest” were not immediately

removed the consequence would be that the area around the works would soon

“become tenantless”. Alexander Ogston (1799)

denied these claims and Dr Jackson and an inspector were sent to examine the allegations

on the ground. Their conclusion was that

there was nothing with which they could find fault and no further action was

taken. Tallow rendering had been in

operation at the site for almost 60 years and the smells generated were

considered to be an inevitable and acceptable consequence to be tolerated in

the interests of the local economy. But

the opposition to Ogstons’ operations inevitably resurfaced, the next time in

1866. A new memorial from complainants

was passed to Alexander Ogston (1799) and he was robust in the defence of his

firm. Ogstons had installed a chimney

which was 120ft in height in order to conduct smells away from the site and to dilute

them in the atmosphere. The only odours

remaining were those due to fresh fatty material and they were unavoidable for

any fat melter. In retaliation Mr Ogston

labelled “one or two neighbours” as being “at constant loggerheads with

everybody and everything round them”.

The whole works were open to inspection and the firm would consider

implementing any reasonable measure to reduce smells. Not all members of the Nuisances Removal

Committee supported the Ogston position but there was no mood to take the

matter any further, the Lord Provost stating that he had been passing Ogstons

for the last 50 years and in that time things had got better. Ogstons had made many improvements and he was

confident that that approach would continue.

Further consideration of the matter was dropped. Another issue affecting relations with the

neighbours of the Soap and Candle Works arose in 1868. As part of Ogstons’

expansion plans, the firm requested permission from the Aberdeen Police

Commissioners to close-up the lane, called Alexander’s Court, running between

Gallowgate and Loch Street on the north side of the Works, so as to allow the

firm to purchase property on the other side of the route. The request was not supported, on the grounds

that the lane was a public thoroughfare for pedestrians. That was not the end of the matter, but it

was the end of Alexander Ogston (1799)’s involvement with it, as the Grim

Reaper called before the next move got fully underway. Alexander Ogston (1799) did have one final

success before his demise. In March

1869, he applied for permission to move the manufacture of composite candles

(and the associated distillation of palm oil) “to a space of ground bordering

on Innes Street and extending about 100 yds back from Loch Street and adjoining

the premises presently occupied by him in Loch Street”. Permission was granted. However, the cause of his death, which was

preceded by a long period of chronic disability (see below), raises the

possibility that Alexander (1799) may only have been indirectly or marginally

involved in the firm’s strategy in the years immediately preceding his demise.

Alexander

Ogston (1799) becomes increasingly wealthy

Although Alexander

Ogston (1799), like his father before him, was largely concerned with the

development of his business, his increasing wealth gave him status in the city

of Aberdeen, disposable income to support causes not directly related to the

promotion of soap- and candle-making and, as the period extended, time to

pursue non-commercial activities.

Further, the acquisition of the Ardoe estate by his father in 1838

brought with it both obligations and expectations that Alexander (1799) would

involve himself in local affairs on Lower Deeside, such as participation in the

activities of the parish church in Banchory-Devenick. His first detected donation to charities

helping the poor was in 1847 when Alexander (1799) subscribed £2 for the relief

of destitution in the Highlands caused by blighting of the potato crop, which had

started in 1846. Other appeals that he

supported included the Aberdeen United Coal Fund in 1854, Indian Famine Relief

in 1861, distress amongst the unemployed in Lancashire in 1862 and relief to

unemployed operatives in Aberdeen in 1868.

Interestingly, the staff of the Loch Street works also made three

separate donations for the relief of the unemployed in Lancashire in 1862. Further, Alexander Ogston (1799) took on the

role of supporting civic society and civic infrastructure, by subscribing to

the St Nicholas belfry appeal, the completion of the Market-house spire in

Stonehaven (the county town of Kincardineshire, the county where Ardoe was

located), the elimination of the debt of the Aberdeen Public Baths and the

Aberdeen Music Hall organ fund.

Significantly, as will later be seen, he also gave money to the City of

Aberdeen Artisan Volunteer Artillery and Rifle Corps. Patriotism was a strong component of his

personal creed and in 1854 he became a member of the local committee supporting

the raising of a Patriotic Fund for the relief of the widows and orphans of

soldiers, sailors and marines killed in the war with Russia. Alexander (1799)’s donations were often in

the range £1 - £3, seemingly trivial sums today, but then worth, in 2021 money,

about £140 - £420. Though Alexander

Ogston (1799) appears not to have been much interested in national or local

politics (he did support the Liberal candidate, J Dyce Nicol, at the general

election of 1865) he contributed in other ways to the development of civic

society, becoming a gentleman member of the Aberdeen Banff and Kincardine

Agricultural Society. His Ardoe

gardener, Peter Elder, was a regular winner at local horticultural shows. In Aberdeen, Alexander (1799) was one of the Dean

of Guild’s assessors and often an invitee to major civic ceremonies such as the

granting of the Freedom of Aberdeen to worthy individuals. He was appointed a Justice of the Peace for

Kincardineshire and in 1844 he was one on a long list of signatories who wrote

to the Lord Lieutenant of the county opposing the repeal of the Corn Laws. The Banchory-Devenick Agricultural Association

held an annual ploughing match, where the ploughmen pitted their skills against

each other and Alexander Ogston (1799), as was expected of major landowners,

contributed to the prize fund.

The death of

Alexander Ogston (1799)

The cause of

Alexander Ogston (1799)’s death was given as progressive locomotor ataxia of 12

years' standing. He died at 9 Golden

Square, Aberdeen and the medical practitioner who certified the cause of Alexander’s

demise was his brother, Professor Francis Ogston, who at the time lived at 156

Union Street, a short walk from Golden Square.

This condition is characterised by erratic movements of the arms and

legs and gets worse over time, due to an advancing degeneration of the

posterior white column of the spinal cord.

There are several possible causes of the condition, including

Huntingdon’s Chorea, pernicious anaemia and multiple sclerosis, but perhaps the

most likely cause in those pre-antibiotic days was chronic syphilis, which is

due to a bacterial infection. However, caution

should be exercised in attributing Alexander (1799)’s condition to a serious

venereal disease, which at this distance cannot be proved, as the agent of his

death.

Alexander

Ogston (1799) had acquired considerable wealth by 1869, the year of his demise. The inventory of his personal estate was

valued at just over £54,560 (about £6,910,167 in 2021 money). His ownership of the candle and soap

manufactory contributed about £40,000 of value to the total. He also owned significant shareholdings in

various banks, insurance and railway companies. There was a touching expression of confidence

in the sense of family cohesion by Alexander (1799), demonstrated by the naming

of his brother Francis, whom he clearly held in high regard, as the sole

trustee of his will, the suggestion that Francis could take advice from his

sons-in-law and his sons to ensure that the father’s wishes were being

appropriately met and, finally, in the fulsome tribute he paid to his wife of

35 years, Elliot. “I commend to your

special care and regard my beloved wife with whom I have so long lived in the

greatest love and affection …”.

Alexander (1799) recognised that he could not exercise absolute control

over his assets from beyond the grave and that he needed to invest in the good

sense and probity of his brother, Francis (1803). Alexander Ogston (1799) was very keen that

his business should continue under the stewardship of his two sons, Alexander

Milne Ogston (1836) and James Ogston (1845), though the company did not come as

a gift to his offspring but as a shared debt to his trust. The new company name and ownership was

announced though the Aberdeen Journal in February 1871, rather more than a year

after the death of Alexander Ogston (1799).

“Notice is hereby given that the representatives of the late Alexander

Ogston of Ardoe, Soap and Candle manufacturer Aberdeen ceased at death on the

11th day of December 1869 to have any interest in the business carried on by

him in Loch Street Aberdeen; and that since that date the subscribers Alexander

Milne Ogston now of Ardoe and James Ogston both residing in Aberdeen have

carried it on and will in future carry it on for their own behoof under the

firm of Alexander Ogston and Sons.

Aberdeen 25th Feb 1871. F Ogston,

Sole testamentary trustee and executor of the late Alexander Ogston of Ardoe”.

Alexander

Ogston (1799)’s family

Alexander

Ogston (1799) and his wife, Elliot Lawrence (1813) had a family of six, four

girls and two boys. Alexander’s sons, as

already stated, took over the running of the Loch Street manufactory. The three girls who survived to adulthood all

made good marriages, though their sister, Helen (1839), died at the tragically

young age of ten years. Elliot, the

oldest girl in the family, married John Miller, the wealthy owner of the

Sandilands Chemical works located next to the Gas Works in Cotton Street. John Miller’s operation was known locally as

“Stinky Miller’s” betraying the nature of his business. At the time of marriage, John Miller was 46

and Elliot Ogston was 25. Sarah Ogston

(1841) was the third daughter in the family, and she married Peter Moir Clark,

a graduate of Marischal College who became a lecturer in Mathematics at

Cambridge University. The youngest girl

in the family was Amelia (1848) who was unmarried at the time of her father’s

death, but who subsequently joined with Edward Nicholls Carless, an MB CM

graduate from Marischal College in 1871.

He subsequently took up a medical practice in Devizes, Wiltshire. The considerable residue of Alexander Ogston

(1799)’s estate was shared equally between his surviving offspring.

Sandilands Chemical Works

Purchase of

the Ardoe estate

The Ardoe

estate had been bought by Alexander Ogston (1766) shortly before he died in

1838 and it subsequently became the country home of his son Alexander (1799)

when he bought the property from the trustees of his father’s estate. During his early career, Alexander (1799) had

generally lived close to his place of work but as the firm became more

successful and he entrusted to others the daily management of the works, he was

able to live, while in the city of Aberdeen, in more salubrious

surroundings. About 1865 he bought a

grand town house, 9 Golden Square. The

medieval street pattern of Aberdeen had been overhauled in the early years of

the 19th century by the construction of Union Street, a wide, long

(about one mile) and handsome (it was progressively lined with many elegant

granite buildings) east – west thoroughfare named after the Act of Union with

Ireland in 1800. This was a major feat

of engineering requiring the partial flattening of St Catherine’s Hill and the

bridging of the Putachieside and Denburn valleys to remove all significant

gradients from the new road. The

crossing of the Denburn was not completed until 1805 and the first major

development west of this location was the construction of Golden Square in

1810. This was a rectangle of elegant

town houses surrounding a central landscaped area opening onto the north side

of the new road. In the first half of

the 19th century, the environs of Union Street were the place where

many of Aberdeen’s wealthy people chose to live. In Alexander Ogston (1799)’s will he gave his

wife two options for her living arrangements after his death. She could either get the life benefits of the

Ardoe lands and estate or receive £450 per year (about £57,000 in 2021 money)

and full possession of the house at 9 Golden Square. In 1871 she was living at 9 Golden Square and

was described as an annuitant, so it appears that she chose the town house

option for her residence. Her sons

Alexander M and James and her daughter Amelia were also resident there on

Census night, all three of them being unmarried at the time. The family was attended by three servants. At the following census in 1881, widow Mrs

Elliot Ogston was still living at 9 Golden Square, and she appears to have

lived there until she died in 1886, after which 9 Golden Square was sold.

A Ogston

& Sons comes into being

The new firm of

A Ogston & Sons thus came into being after the death of Alexander Ogston

(1799) in 1869 and was described as “Alex. Ogston & Sons, Soap and Candle

Manufacturers, 92 Loch Street” in the 1870 edition of the Scottish Post Office

Directory for Aberdeen. Two sons were

involved in the management of the new entity, Alexander Milne Ogston (1836) and

James Ogston (1845) and at the time of their father’s death, they were

respectively 33 and 24 years of age.

Alexander Milne had been working in the old firm since 1855, aged 19,

though it is unclear when brother James started work in the soap and candle

business but at this early stage of their collaboration, Alexander Milne was

clearly the more senior in terms of age and experience of the business. AM Ogston’s education has only been barely

uncovered. At the age of 12 he was a

pupil at the Writing and Drawing School of Mr Francis Craigmyle, where his

performance was judged to be only 3rd class in writing, but that had

improved to second class by the following year.

Two years later his performance was estimated as first class. It is possible that he also attended Aberdeen

Grammar School before entering the family firm, since in 1906 he was invited to

attend the Aberdeen Grammar School Former Pupils’ Club reunion. Perhaps, because his father had early

designated him as a successor in the Soap and Candle business, no thought was

given to Alexander Milne pursuing higher education. The education of James Ogston (1845) has only

been uncovered in outline. In 1853 he

too attended Mr Craigmyle’s classroom in writing and drawing in Aberdeen, where

he was a prize-winner. Subsequently, he was

a pupil at Dollar Academy, five miles east of Stirling. For both sons, their most formative

educational experiences were probably encountered within the firm. For each it was a case of “learning by

doing”.

More trouble

with the neighbours

Probably the

first major issue to confront the Ogston brothers arose even before the death

of their father in December 1869. A

month before this tragic event, a further memorial was presented to the

Aberdeen Police Commissioners by 179 disgruntled neighbours of the Soap and

Candle Works claiming that Alexander’s Court had always been a public

thoroughfare and therefore could not legally be blocked by Ogstons with a

paling fence at both ends, as appeared to have happened. Was this the high-handed action of the Ogston

brothers, in a hurry to get on with the development of their new commercial

charge? Ogstons, through their legal

agent, C&PH Chalmers, denied that Alexander’s Court had even been a public

thoroughfare and the matter was referred for decision to an open committee

along with the Law Agent. But local

feelings were running high, and the protesters were not prepared to wait for an

official decision on the matter. Direct action ensued two weeks later when a

crowd of men attacked and destroyed the fence at its Loch Street end before

moving on to the other barrier, which received similar treatment, despite

Ogston’s employees hosing down the protesters.

There was no intervention by the police.

By the next morning, Ogstons had replaced the barriers with structures

of a more robust construction. This

further aroused the ire of the protesters who descended on the new structures

and again smashed them, along with some of the Works’ windows, despite again

being sprayed with water in the cold of an Aberdeen December. The police were present but “with the most

imperturbable coolness enjoyingly surveyed the animated scene and, for once at

a scrimmage, took the side of no one”.

It was rumoured that this inaction by the arm of the law was due to a

Police Commissioner actively sympathising with the cause of the mob. The barriers were not re-erected and Ogstons

decided to await the emergence of a legal decision.

The Police

Commissioners seemed to struggle to reach a decision in the Alexander’s Court

case because by May of the following year no conclusion had been announced,

when a further petition was presented by 12 locals, perhaps fearing the worst,

asking the Commissioners to look after the interests of the residents, should

Ogstons again try to block access. The

Dean then visited the Court and found that it was not shut off. Also, he had been assured that Ogstons had no

plans to do so. Matters remained calm

until November 1870, when the unhappy residents of the Loch Street area

convened a public meeting to discuss Alexander’s Court. The conclave passed three resolutions. Firstly, that the Police Commissioners had a

duty to maintain intact every street, lane, court and alley for the use of the

community and secondly, to assert that Alexander’s Court had been a public

thoroughfare since “time immemorial” and that the Police Commissioners must

take action to maintain that right. The

third resolution established a committee to carry out the first two

resolutions. About this time, Alexander

Milne Ogston (1836) must have realised that an overly legalistic approach, even

if formally successful would only exacerbate the bad feeling which had

developed between A Ogston & Sons and their neighbours. AM Ogston had sought an interdict against Mr

Gall, a grocer located in the Gallowgate, who appears to have been one of those

leading the protests, but Ogston now changed tack and withdrew the

interdict. In any case the protesters

appeared to have established a good case that a right of way had existed over

Alexander’s Court for at least the previous 40 years.

The new tactic

by Ogstons, actually a very old tactic, was to offer money for compliance, on

the basis that everyone has his price.

Their revised proposal was to shut Alexander’s Court, not in its

entirety but partially from the Loch Street end to a point 212ft distant. C&PH Chalmers put the proposal to the

Town Council in the names of A Ogston & Sons, AM Ogston, J Ogston and

draper Mr John Alexander, the owners of the court and pointing out that it was

within the Council’s power to act, the alleyway being less than 12ft wide and

suitable only for foot traffic. At its mostconstricted

it was very narrow, only 3ft 3in wide. Ogstons

offered £100 for the right of servitude the protesters alleged they would lose

over the closed portion of the court.

The new proposal was considered by the Council in mid-December

1872. The reason given by Ogstons for

the proposal was that it would allow them to make alterations to their

manufactory which would make their operations more acceptable to the general

public than had apparently been the case hitherto. Two petitions were also tabled at the Council

meeting, one from 66 persons objecting to the closure. However, Ogstons had organised their

supporters by this date and the contrary position was taken by 185

persons. The Council resolved to agree

the closure and, of course, to accept the £100 (about £12,000 in 2021 money),

to be used for improving access on other routes in the neighbourhood.

Though this

long-running dispute had at last been resolved, the year 1872 brought further

local difficulties for Ogstons. The

Sewerage Committee of the Town Council received a report that the main sewer in

Loch Street had become blocked and that on clearing it out, it was found that

the cause was discharged material from the Soap and Candle Works. A bill for clearance was sent to

Ogstons. Early the following year

another petition was submitted to the Town Council from 20 residents of the

Loch Street area again complaining about the offensive odours emanating from

Ogstons’ Works. The complaint was

forwarded to the Public Health sub-committee for consideration, which it did a

month later. By the time of the meeting,

support for the complaint had grown to 317 local residents, all of whom had

signed a memorandum. The objectors had,

rather unrealistically, demanded the removal of the works from that location. The sub-committee made a site visit before

making a response. At Loch Street “they

found that the large number of workmen employed at the works enjoyed good

health; the result of their own visit was not unsatisfactory and beyond

suggesting one or two improvements which Messrs Ogston promised to attend to,

the sub-Committee could not recommend the Local Authority to interfere further

in this matter”. It was later confirmed

by Dr Littlejohn of Edinburgh that Ogstons had carried out the agreed

improvements satisfactorily. The smells

had been minimised and there had been no recent complaints.

A Ogston

& Sons’ business grows

From the year

1874, it was clear that A Ogston & Sons was importing an increased quantity

of raw materials for soap and candle manufacture by sea from continental

Europe. Between this year and the end of

1877, the following totals were detected, 13cwt + 32 cases paraffin, 87 casks

of potash, 25 casks of silicate of soda and 8,575 bundles of hoops, presumably

for the manufacture of barrels in Ogstons’ cooperage. Another interesting statistic, bearing upon

the scale of the Soap and Candle Works operations, was the purchase of 22 tons

2cwt of tallow from Mr Murray’s market in Banff in a single week late in 1876

and in 1879 tallow was imported from New York and a substantial consignment of

rosin from Savannah. At some point in

the, then, recent past, the firm had also imported potash from Canada.

This growing

dependence on sea transport caused A Ogston & Sons to write to the Aberdeen

Harbour Board in 1885 pointing out that the dues charged locally on materials

imported and exported were substantial and put Ogstons at a competitive

disadvantage with manufacturers located further south. They had to compete with producers who were

more favourably situated with respect to transport costs. The letter instanced paraffin, scale and palm

oil, the dues on which were 2/- per ton.

When manufactured into candles and again shipped, as a considerable

proportion of them were, 2/- per ton outwards had again to be paid and being

charged on the gross the cost for dues alone both inwards and outwards amounted

to 3d per cwt in the manufactured article.

Tallow, rosin and oils (such as cotton and linseed) were subject to the

same rate of dues and also soaps which they had to deliver in the south markets

where competition was so strong that they were almost run out of the market and

3d per cwt was often the limit of the profit they could realise. But it appeared that the Harbour Board was

immovable.

The year 1877

saw further plans for the expansion of the Soap and Candle Works. Planning permission was granted for a new

warehouse, tallow house and packing room on the part of the site adjacent to

the Innes Street junction with Loch Street.

The architectural practice responsible was William Henderson & Son. Further proposals to make alterations to the

Works were sent to the Town Council in 1883 but the local authority deemed them

to be outwith the need for planning approval, since no expansion of the works

was involved.

Eighteen

eighty-six provided a good illustration of the way in which the relationship

between the Town Council and A Ogston & Sons had matured. The location of the Soap and Candle Works,

together with the nature of its business and the ambition of its owners, adjacent

to domestic housing led to periodic complaints concerning smell and

access. The Council found itself “piggy

in the middle” between the populace whose concerns they had to handle and a

major firm with a substantial impact on employment and the economy of the

area. The Town Council’s Streets and

Roads Committee proposed to construct a new road between Gallowgate and Loch

Street on the line of Livingstone Court.

However, Ogstons had their own plans for the further development of

their site, which included building over a portion of this Council-proposed

access route. The Town Council wisely

sought to find an accommodation with the firm by sending the Lord Provost “to

wait upon Mr Ogston (Alexander Milne Ogston) to see if a way can be

found to keep the Town’s plan viable”.

AM Ogston (1836) wisely accepted this olive branch and agreed to give up

the firm’s right to build over part of Livingstone Court, so as not to

compromise the Town’s scheme if, in return, the Council would pay for the

construction of the gable end of the relocated building at a cost of £60 (about

£8,300 in 2021 money). The Council

readily assented to this quid pro quo and both sides emerged from a

potentially confrontational situation having achieved a win-win outcome. Ogstons were praised for approaching the

problem in a liberal spirit and they also gifted the solum of the ground

required by the Council for their new road.

In 1891, A Ogston & Sons proposed yet further expansion and modification to their works on the Gallowgate side. The Public Health Committee of the Town Council examined the proposal and quickly gave their approval, conditional on the business "being conducted so as not to be injurious to health". The new development involved the demolition of numbers 123 to 135 Gallowgate and their replacement with a new structure to be used as casemekers' shops and wood stores. A further proposal by Ogstons was made two years later and it too received a rapid sign-off from the Council. As if to emphasise the almost continuous nature of the development of the Loch Street site, in 1895 Ogstons proposed the construction of a chimney stack and also further reconstruction of existing buildings to be used partly as carpenters' and blacksmiths' shops, partly as stores, partly for the cutting and stamping of soap and finally a small portion to be occupied as a bothy.

Accidents at

A Ogston & Sons’ works

Given the growing scale of the operations of A Ogton & Sons, it was inevitable that an increase in industrial accidents would be a consquence. In 1876 a horse-drawn lorry was standing in the Soap and Candle works with a load on empty firkins when some fell off, panicking the horses and knocking down the two men in charge, both of whom were injured, one seriously. A gale in 1887 dislodged some iron sheets from the works and they struck a passing girl who was “seriously” injured and taken home in a cab. Accidents also happened from time to time as a result of the inappropriate use of machinery. In 1887, a boy worker tampered with a cutting machine in the tinsmith department and had the fingers of one hand almost severed. On admission to the Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, it was found that the fingers were so badly damaged that they had to be amputated. A similar incident occurred a few months later when another boy lost two fingers in a die-cutting machine. An even more serious accident occurred in 1890 when a blacksmith fitting gas piping stepped back to look at his work and fell 24 ft down a lift shaft, sustaining a compound fracture of the skull. He died in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary a week later. Three years on, a similar accident occurred to a young employee, Andrew Frost aged 15, who stepped back into a tank of boiling water and was badly scalded on the legs.

Advertising

by A Ogston & Sons

Following the

success of the Great Exhibition of 1851, international displays of manufactures

became popular in all industrial nations.

Participation was deemed an effective way to bring a firm’s products to

the notice of the consuming public. In

1886, such an exhibition was held in the Scottish capital, the Edinburgh

International Industrial Exhibition. It

was opened by Prince Albert Victor, the eldest son of the Prince (later Edward

VII) and Princess of Wales. A Ogston

& Sons was one of the exhibitors and the most prominent feature of the

firm’s display was “a colossal obelisk of soap surrounded by a very large

collection of small pieces of the same material, illustrative of all the

varieties manufactured in the works as well as by numerous specimens of candles

from the plain to the coloured and decorated lights of the most artistic moulds”. A jury awarded prizes to exhibitors and

Ogstons received a gold medal and a diploma for soap and candles. That Ogstons had chosen to be represented at

such a gathering illustrates well the scale of their ambition at that time. Subsequently, Ogstons were represented at

other similar exhibitions, for example at Newcastle in 1887 and at Glasgow the

following year. On this latter occasion,

Ogstons exhibited a machine for plaiting candle wicks based on a new principle

of operation.

During the period when they held an agency agreement (1845 – 1861) with Price for the sale of the London firm’s candles, Ogstons often placed advertisements in the local papers and these inserts always emphasised the enterprise’s link to this leading candle manufacturer. Subsequently, Ogstons, being a wholesaler, seemed to leave advertising to the initiative of their retail suppliers. For example, in 1866, Hutcheon’s Light Stores, Turriff, advertised “Young’s Patent Paraffin 3/6 per gal. Miller’s Naphtha 2/6 per gal. London Pale Seal Oil 4/8 per gal. Ogston’s Composite Candles, fine 0/8 per lb. Ogston’s Composite Candles, crown 0/9 per lb” in the Banffshire Journal. This situation continued until about 1888 when Ogstons started to identify their products with brand names and, in addition to the advertisements by their retailers, launched major advertising campaigns of their own. The first brand name that they used was “Balmoral”, thus creating an unofficial link to the Royal family, though they did not hold a Royal warrant for the supply of soap. “Balmoral Paraffin Soap is the latest laundry surprise. Is a speedy and effectual washer. Is non-injurious to clothes or skin. It leaves no smell after washing. Is an economical soap to use. Manufactured by Alex Ogston & Sons, Aberdeen”. This advertisement appeared in all the local Aberdeen newspapers in the summer of 1888. Other advertisements started to emphasise the status of the manufacturer, “Each bar bears the stamp of the well-known soap manufacturers, Alex Ogston & Sons, Aberdeen whose brand on any soap is a guarantee of its genuineness. All inferior makes should be avoided”. By the following year, 1889, searches for the word “Ogston” in newspapers published in the North-East were dominated by insertions extolling the virtues of Ogstons’ soaps, such was the impact of the change in advertising policy. These themes of emphasising brand names and the status of the manufacturer continued. The following example was from 1889. "Ogston's Prize Medal Finest Pale, Crown Pale and XX Pale Soaps in 4b and 4 1/2 lb bars. Are unadulterated. The maker's name is stamped on each bar for the public protection, Ogston's finest soft soap is absolutely free from smell. Every cask or tin that bears Ogston's name is genuine and full weight. Ask your grocer for Ogston's and take nothing else".

Local

competition for soap and candles - consolidation

One of the

stimulants of this move into advertising by A Ogston & Sons was undoubtedly

competition locally from other manufacturers.

As has been shown above, in the second half of the 18th

century soap and candle manufacture in Aberdeen was characterised by the

existence of a shifting population of small producers, individual members of

which seldom survived for more than a few years. The situation changed around the turn of the

century when some manufacturers appeared, other than Ogstons, which had greater

staying power. Copland & Milne

produced candles and soap between1799 and 1827, John Bothwell, followed by his

son George, was a candle manufacturer between 1798 and 1857, PA Skinner

produced candles from 1824 to 1866, William Borthwick made candles from 1822 to

1839, Alex Mears was a more transient soap producer from 1817 to 1825,

similarly with Robert Shinnie whose soap was sold between 1799 and 1810. However, after the demise of PA Skinner in

1866, Ogstons only had two significant local competitors, the Lilybank Soap

Company which started producing both soap and candles in 1884 and Williamson

& Middleton (succeeded by Williamson & Simpson) who manufactured only

candles from 1834 to 1866 and then both soap and candles from 1867 to

1902. In effect, the scale and

efficiency of the Loch Street Soap and Candle Works saw off all local

competitors apart from these last two rival firms and Ogstons (which was transformed

into Ogston & Tennant Ltd in 1898) found a method to eliminate the last of

the local Aberdeen competition.

The Lilybank

Soap Company was incorporated in 1884 with a capital of £30,000. Its objective was to carry out the

manufacture and sale of soap, candles and margarine and the buying and selling

of oil and tallow and other kindred commodities but with an initial

concentration on soap manufacture. The

company said of itself “The trade is in few hands and is known to have yielded

good returns to those having at their command ample capital and efficient

management”. To which Aberdeen soap

manufacturer could those in the new company have been referring? The name of the new company was derived from

a site at Kittybrewster station called “Lilybank”. A licence for manufacture was granted in July

1884, subject to regulations based on those imposed “in other places” and by

January 1886 its new, commodious premises had been completed. In 1886, the first year of production, the

company made a small profit of £103, declining to a loss of £250 in the

following year, though an air of desperation was evident when the board

appealed to shareholders not to buy their groceries from agents who did not

stock Lilybank soap. The company’s soap

was heavily advertised in the local press, with Ogstons retaliating in

kind. Eighteen eighty-eight saw a profit

of £380, even after paying down some debt and it appeared that this neophyte

had at last overcome the teething troubles that can afflict any emerging

firm. A new chimney stack and boiler

house were added to the premises but at the end of the fifth year of its

existence the company’s debt had started to mount, no dividend was declared,

and the share price fell. A rumour then

appeared in the press alleging that Lilybank was to be amalgamated with a

company from the South. This caused Alexander

Milne Ogston to contact Mr Esslemont MP, the chairman of Lilybank, to ask if

the company was for sale. He must have

received a positive response because Ogstons then offered a cash price of £9088

(about £1.25 million in 2021) to buy the ground, buildings, machinery and plant, and office furniture of their competitor in Kittybrewster.

The directors met to review the offer, considered it fair and

recommended acceptance at a meeting of shareholders. The sale was agreed. The Lilybank Soap Company Ltd had existed for

little more than six years before being swallowed by its larger neighbour.

The firm of

Williamson & Middleton started making tallow candles under the partnership

of James Williamson and James Middleton at premises in Wales Street, Aberdeen

in 1826. At the time, James Williamson,

who had been a flesher (butcher) was 41 and his partner was four years his

junior. A year later, they took on an

additional partner, William Reid, who was also a flesher. The firm was

successful and continued in business, regularly exporting candles to Halifax,

Nova Scotia, until 1848 when it was dissolved by mutual consent, apparently due

to the advancing years of the partners, both retiring from the chandlery

business. James Williamson died a year

later. Technically, the firm of

Williamson and Middleton ceased to exist but practically it continued, occupying

the same premises but under a new partnership of William, the youngest son of

James Williamson, and John Simpson. The

new firm was called Williamson & Simpson.

In 1867, the scope of the firm’s business expanded to include soap-making

and dealing in oil. The success of this