Introduction

In 2020 I published

an account of the life of David Kinloch Michie, the notorious Perthshire poacher,

on this blogsite. Much of the story

depended upon a newspaper article entitled “Famous Scottish Poachers” which appeared

in “Weekly News” in 1904. The unknown

author of this piece admitted that the infamous offender represented there was sailing

under the pseudonym of “Donald Gow”, which left open the issue of what other

“facts” given in the story had been altered.

The tale was also marked by a dearth of dates and timescales. Further, no sources were given for the

incidents portrayed. However, the

conclusion that I reached was that “Donald Gow” and “David Kinloch Michie” were

likely one and the same person.

In summary, the

article described the following characteristics of “Donald Gow” and various

incidents from his life.

He was probably

the most famous poacher in Perthshire in the 1830s and 1840s, though his career

did not extend for many years. “Gow” was

big, strong and given to threats of violence in order to evade capture, and the

local gamekeepers were generally afraid of him.

He had a brother, “William”, who acted as a restraining influence on him. “William” died young but not before he lost

several fingers on his left hand when his gun exploded.

On one

occasion, “Donald Gow” and a companion were pursued by a posse of local people,

including a policeman and a gamekeeper, intent on capturing the miscreants, who

were out on a poaching expedition. On that

occasion, threats of violence were not sufficient to deter the pursuers and

both “Gow” and his accomplice fired on them, injuring the policeman and others,

before “Gow” and his companion escaped.

He was then outlawed. In

consequence, great efforts were made to apprehend “Donald Gow”, but without

immediate success.

The article

claimed that the subsequent failure to find “Gow” was because he changed his

appearance, shaved off his beard, and joined the Aberdeenshire Police Force,

where he was even tasked with detecting and detaining himself. During his police service he became

acquainted with a widowed lady of high rank who had a shooting lodge on an

estate. She and her guests found “Donald

Gow” attractive because of his good looks, an imposing personality and a knowledge

of country sports. She then invited him

to leave the police service and become her gamekeeper.

However, “Gow”

could not do this while he was outlawed, so he confided his story to her, and

she agreed to do all in her power to free him from the consequences of his

violent actions. This proved to be no

easy task but may have finally been accomplished by her paying a substantial

fine on his behalf to obtain his pardon.

“Donald Gow” then joined her service as a gamekeeper.

In his

subsequent life, “Donald” became a reformed character and a respected member of

his community.

The present

revisitation of the life of David Kinloch Michie has sought to further

knowledge of his background and life from independent sources, in order to test

the claims made in the “Weekly News” article.

Although not all aspects of the story have been verified, many have,

including the identity of the widowed lady of influence. She proved to be Georgina, Dowager Duchess of

Bedford, as suspected in the original article.

She was a quite remarkable woman with her own colourful life story,

which is directly relevant to the present tale.

Additional relevant facts have also been uncovered which support the

“Weekly News” story, if not directly, at least circumstantially.

David

Kinloch Michie’s family background

David Kinloch

Michie was the seventh child in a family of eight. His father was John Michie, b1773 at Caputh,

a village on the north bank of the river Tay, about 11 miles north of the

county town of Perth. In 1806 he married

a local girl, Isabella Anderson. Their

children were Charles Kinloch Michie, b 1807; William Michie, b1809; John

Michie, b1812, Isabella Michie, b1813, Margaret Michie, b 1815; Jemima Michie,

b 1817; David Kinloch Michie, b 1820; and Alexander Michie, b 1823.

John Michie

(1773) and his wife Isabella spent their whole lives in an area centred on the

joint parish of Kinloch and Lethendy, which was created in 1806. It lay

four miles south-west of the town of Blairgowrie and was bounded on the east by

Blairgowrie, on the south by Caputh and on the west and north by Clunie. Its greatest length, east to west, was five

miles and its greatest breadth, north to south, was 1½ miles. In 1845, the three main landowners in the

parish were Andrew Gemmell of Lethendy, Sir John Muir Mackenzie of Delvine and

David Kinloch of Gourdie. The last named

had the smallest holding of the three.

In 1841 the parish population was 369.

John Michie (1773) worked for the Kinloch family as the manager of their

lime works, located at the southern end of the Loch of Clunie, near the village

of Craigie, but lying within the parish of Caputh. He is known to have fulfilled this role at

least between 1812 and 1828. It is

possible that his two sons who received the given name of “Kinloch” were named

after David Kinloch, 4th Laird of Gourdie (1736 – 1818) and Charles

Kinloch 5th Laird of Gourdie (1788 – 1828) respectively. Subsequently, and at least by 1832, John

Michie (1773) became a farmer at Cowford farm which lies about 8 miles south of

Blairgowrie.

The area of

Perthshire with which the Michie family was familiar was replete with large

estates, often with much hill land which was devoted to sporting activities,

such as grouse and hare shooting, and deer stalking. Gamekeeping was a frequent calling of the

rural working class in these localities.

Sporting dog breeding was another activity associated with the provision

of services to the wealthy hunting and shooting set. An inevitable adjunct to such sporting

pursuits was the illegal taking of game by poachers, some of whom were

professionals, making a living from the sale of their kill. The skills required to be an effective gamekeeper,

or a successful poacher were essentially identical, and the five sons of John

Michie (1773) pursued both callings, sometimes alternately.

According to

the “Weekly News” article, “Donald Gow” had a brother “William” who was also a

poacher but who had a milder and more balanced temperament than his impetuous

younger sibling, often holding the head-strong junior in check. David Kinloch Michie had a brother named

William Michie, but he did not die young, which does not fit with the life of

the brother “William” in the article. It

is likely that this more balanced brother was actually Charles Kinloch Michie

(1807), who died in 1840, the name switch probably being part of the “Weekly

News” article’s author’s strategy of obfuscation.

In 1829 and

1830, William Michie (1809) was a gamekeeper acting for Sir David Moncreiffe

(1788 – 1830) over his lands at Moncreiffe, Bridge of Earn, Perthshire, where William

held a schedule B game licence. By 1831,

William was wealthy enough to be able to afford a schedule D game licence,

costing over £4 (about £316 in 2022 money), for land at Kirkmichael. But William was also a poacher. A warrant was issued for his arrest early in

1839 for illegally taking game and he was detained near Blairgowrie. However, he avoided a custodial sentence by

paying a fine. In 1840, 1841, 1844, 1850

and 1851, he is known to have held schedule D game licences, but this time over

land at Cowford, probably the land of his father’s farm. At the 1861 Census of Scotland, William was

again recorded as following the calling of gamekeeper, as he was living at the

Gamekeeper’s House, Kirkmichael.

Possibly he was working for the owner of Ashintully Castle.

In 1828, 1829

and 1830, “Mrs Captain Kinloch”, probably the wife of Captain Charles Kinloch,

5th Laird of Gourdie, provided schedule B certificates for a John

Michie to act as gamekeeper over lands at Gourdie, the location of the Kinloch family

seat. This John Michie is likely to have

been John Michie (1773), who had probably retired from managing the Gourdie

lime works by this year. His son, John

Michie (1812) would likely have been too young at 16 years in 1828 to have

acted as a gamekeeper. However, by the

1841 Census of Scotland, John Michie (1812) was found, with his wife Charlotte,

living at Alvie, Invernessshire.

Further, the year and place of birth of his first child, 1836 at Alvie,

suggests John and Charlotte had been at Alvie since at least that year. His employer and his exact employment role at

that time have not been discovered, but in the following census of 1851 he was

a gamekeeper living at Pitourie, Alvie.

Thus, it is likely he had been a gamekeeper, or perhaps an underkeeper,

there for more than a decade, between the ages of 24 and 39. What is utterly fascinating is the discovery

of his employer. In 1843 and again in

1844, John Michie held a class B game certificate over the lands of Kincraig

and his sponsor was Lord Edward Russell (1805 – 1874), the second son of Lord

John Russell and his second wife, Georgina.

The Kincraig shootings were near the Doune, Lady Russell’s leased,

seasonal home on the Rothiemurchus estate.

John Michie was responsible for game preservation at Kincraig, at least

in 1843 and the further years of 1848 and 1851, but in these latter two years

his sponsor was Georgina, the Dowager Duchess of Bedford. The likely significance of these findings is

discussed below.

Alexander Michie (1823) was the youngest of John Michie (1773)’s sons. At the 1851 Census, he was a farm labourer on his father’s property at Cowford. During the previous year he held a schedule B game certificate for the land at Cowford, as did his brother William. In the years 1854 and 1855, Alexander was working as a gamekeeper for RJR Aytoun Esq, a retired military officer and the occupier, over lands at Ashintully Castle, Kirkmichael. Alexander apparently continued in his calling of gamekeeper, as in 1861 he was described as a gamekeeper living at “Gamekeeper’s Lodge”, Minnigaff, Kirkudbright, in the south-west of Scotland.

David Kinloch

Michie (1820), in contrast with his brothers never held a game certificate,

either as a gamekeeper or as a landowner or occupier, prior to the period during

which he was outlawed (1840 – 1845). It

is likely that he took up poaching as a way of earning his living before 1839,

but the precise year has not been uncovered.

After his arrest he would claim that he ceased living at his father’s

home between the ages of 10 and 15 (1830 – 1835) but given the devious content

of the rest of his statement, no reliance should be placed on this

assertion. There is no doubt that David

Kinloch Michie was a wild character, fathering three children by two different

mothers before and after he was declared an outlaw in April 1840. The first of these “natural” children must

have been conceived about the beginning of September 1838, probably at

Blacklunans, Angus, with 19-year-old Ann Stewart. Blacklunans, although in a different county,

was only about five miles east of Kirkmichael (the scene of David Kinloch’s

crime of shooting at a policeman) and 16 miles north of the town of Blairgowrie. Cowford farm was about 10 miles south-west of

Blairgowrie. The second illegitimate

child was conceived about the middle of December 1839 with a different woman,

Ann Healy. The child, Adam Moncur Michie

was born in the parish of Lethendy and Kinloch, where David Kinloch had

previously lived until about 1830. The

third extramarital conception again involved Ann Stewart and occurred about

March 1843 while he was on the run. This

child, Helen, was also born at Blacklunans.

It is likely that all three “natural” children were conceived during

David Kinloch Michie’s poaching career, one before the shooting offence, one

about the time of the shooting incident and the third during his outlawed

state.

The Michie

family and poaching

It is likely

that all the members of the Michie family were aware of both the gamekeeping

and poaching activities, from time to time, of various family members. A report in the Perthshire Constitutional of

13 February 1839 is particularly informative about the activities of the

Michies and the involvement of publicans in the supply chain for disposing of

illegal game.

“Poaching seems

to be on the increase in this neighbourhood (Dunkeld), in spite of the

vigilance of the keepers and their assistants.

On the evening of Monday 28th ultimo no less than five

regular poachers and two “cockers” (a “cocker” appears to have been a

receiver of poached game) were snugly ensconced in the house of James

Miller, publican – and there over a flowing bowl of mountain dew, busy driving

a bargain of their ill-gotten gear – when lo! H Ritchie, Messenger-at-arms,

Dunkeld, with a party, “entered appearance” and disturbed not a little the

harmony of the company. A scuffle

ensued, but in the end he succeeded in apprehending two of them, against whom

he had warrants, namely William Michie (brother of David Kinloch Michie)

and Alexander Kennedy (who would be the companion of David Kinloch

Michie on the occasion when the policeman was wounded), well known

characters. Michie has before this been

repeatedly “taken into custody” by the Blairgowrie officials, but he just as

often bade them good day (ie escaped).

He, however, on this last occasion, saw there was no joke in the matter,

and prudently dispatched a message for a friend who relieved him from the

dilemma, by paying down £6 being the contents of the warrant against him,

consequently he was set at liberty.

Kennedy was less fortunate however, for having neither friends nor

money, he was “bagg’d” and carried off, and safely put into winter quarters in

Perth jail under Mr Hutchison the “keeper” thereof where he will likely have

other game to hunt. It has been

whispered too that the Surveyor of Taxes for the District means to have him

convicted for shooting without a licence – whereby it is more than likely he

may pass the summer in “safe custody”.

It may not be out of place here to observe that more than one publican

in the Upper Stormont District makes a good job of it by harbouring poachers

about them. (Stormont is one of the

ancient divisions of Perthshire, between the river Tay and the river Ericht,

and the Upper Stormont District includes the area around Kirkmichael). These publicans take the guns from the

poachers and in return supply them with mountain dew (whisky) and the

necessary requisite - powder and shot.

Again, the “cocker” comes round weekly and relieves the publican of his

ware, when a balance for the time being is struck betwixt the parties. Were the publicans looked after more strictly

and their licences where guilty of the above practices forfeited, poaching

instead of increasing would soon be on the decline. Something must soon be done to check this

growing evil”. (David Kinloch Michie

is not named in this account but he may have been one of the poachers who avoided

detention).

The fact that

the Michies could afford to pay a £6 fine and also be able to afford schedule D

game certificates (£4+) suggests that the family was not short of money, and

also that the money may have been, at least partly, derived from “the growing

evil” of poaching. The Perthshire

Courier of 2 May 1839 reported briefly that “some poachers” (not named or

numbered) had been fined a total of 17 gns at Dunkeld. Heavy fines did not seem to deter poachers

suggesting that it was a lucrative profession if participants could avoid

detection for most of the time.

David

Kinloch Michie and the shooting of the policeman

David Kinloch

Michie and Alexander Kennedy were observed in poaching activities on Thursday 19th

and Friday 20th December 1839 by Thomas McGlashan the farmer at

Cultalonie, near Kirkmichael. This

sighting was immediately before the notorious shooting incident and occurred on

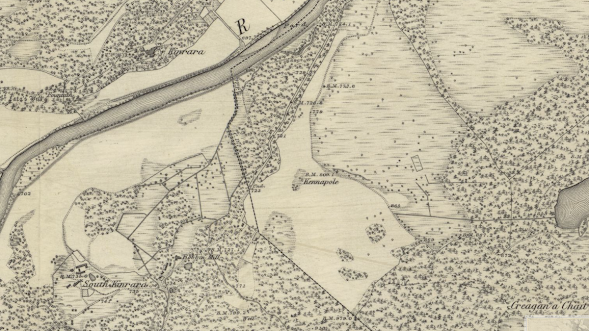

lands belonging to the Kindrogan (or Kindroggan) estate, located about a mile

south-east of Kirkmichael and on the west bank of the river Ardle. Kindrogan House is situated about two miles

north-west of Kirkmichael and, at the time, it was owned by Mr Peter Small Keir.

Michie and Kennedy, through their local

notoriety, were known to some of the witnesses and quickly identified.

On the morning of

the next day, 21st December, Alexander Fraser, the tenant of Mains

of Downie (or Dunie) was travelling on horseback to Pitkermack (or Pitcarmick)

when he met Alexander McKenzie, the overseer at the farm of Balmyle, who told

him that there were poachers in the woods.

He had also seen them two days previously and knew them to be David

Kinloch Michie and Alexander Kennedy.

McKenzie said that he had almost been shot by Michie but thought that

Kennedy had restrained him. It was very

often the case that tenant farmers were obliged, by the terms of their leases,

to defend the game on their grounds and that was so in this case.

Fraser and

McKenzie spotted the two men, with guns and dogs, on the face of the hill near

Pitkermack, where there is a bridge over the river Ardle. The two farmers went to the bridge intending

to intercept the poachers and two other men then joined them. Henry Rattray,

the farmer at Stronamuck, who had also seen Michie and Kennedy shooting and had

approached them, with the result that they retreated towards the river. A fourth man, James Stewart, a farm servant

at Cultalonie, on the instruction of his master, Alexander Fraser, also joined

the others to form a posse. However, the

two poachers tried to cross the Ardle by wading to avoid the men waiting at the

bridge. Alexander Fraser then approached

the miscreants, but they turned, raised their guns and threatened to shoot him

if he came nearer. Frightened by this

warning, Fraser backed off and returned to the bridge. The poachers found that they could not wade

the river because of the force of the current.

Henry Rattray confronted them when they came out of the water, but they

also threatened him with violence. “I

did not know the men, said Rattray, “one of them was much taller than the other

and both of them had double guns. When

they saw that they couldn’t wade the water, they turned round and threatened to

shoot me. I said I was not afraid of

them when both of them threatened, with great oaths, that they would make a

saddle of my skin and send me to eternity and the other, seeing this, struck me

a severe blow or thrust with the muzzle of his gun on the side at the same time

saying “damn spie””.

The poachers

then had to descend to the bridge. Fraser tried to grab the taller man (David

Kinloch Michie) but he was repelled with a push from the poacher’s gun. The posse, Fraser, McKenzie, Rattray and

Stewart, followed the fugitives to the north side of the Ardle. Michie, after crossing Pitkermack bridge,

which was the limit of the Kindrogan land, then turned and threw a stone,

hitting Fraser on the feet. The poachers

then travelled over the road, which ran from Kirkmichael to Bridge of Cally,

and headed up Balnabroich Hill with the constable, gamekeeper and other

followers in pursuit.

By this time

further men, including Alexander McDonald, the gamekeeper at Kindrogan, John

McIntosh, constable in the Perthshire Preventive Police Establishment in the

parish of Kirkmichael, who lodged at Cultalonie, Robert Murray, farmer at

Dalvie, and his son John had joined the pursuing pack. Alexander McDonald was present at Pitkermack

to shoot hares and woodcock when he saw the pursuit and joined in the

chase. Alexander McKenzie appeared no

longer to have been with the group after they crossed the bridge over the Ardle. He stayed on the opposite hillside and was

able to witness the events which unfolded on the north side at a safe distance.

Balnabroich

Hill was the property of James Valentine Haggart Esq. and his wife Amelia of

Glendelvine but was farmed by Lauchlane (or Lachlan) Robertson, farmer at

Balnabroich and a number of other, smaller tenants, Alexander Batter, farmer at

Stylemouth, Colin Campbell, farmer at Ballinluig and John McIntosh, farmer at

Easter Downie (apparently no relation to the constable of the same name). The place where the shooting occurred was on

land common to all the Balnabroich tenants.

When the

poachers started their ascent of Balnabroich Hill they were not running,

perhaps trying to assume an air of unconcern.

The followers were about 40 or 50 yards behind. Henry Rattray was leading a pony, but John

McIntosh mounted it and took to the front in chasing after the retreating men. One of the pursuers, Alexander McDonald, was

close by farmer Robert Murray and they reached to within about 15 yards of the

retreating poachers. McDonald called on

the poachers to stand but the response was that the followers would be shot. “Michie swore by God that he would make

corpses of us”. McDonald also had a

Newfoundland dog with him which “gambolled” with the poachers’ two dogs, a

pointer and a setter. Michie and Kennedy

aimed their guns at the keeper’s animal, and he appealed to them not to shoot

it, as it would not harm them.

The threat from

the poachers had its desired effect and the two men then dropped back until the

rest of the group caught up with them, before resuming their pursuit

collectively. However, when Michie and Kennedy passed the

head dyke on the part of the hill common to all tenants they then turned, threw

down their bonnets and game bags and raised their double-barrelled shotguns to

their shoulders. Michie was the first to

fire at his pursuers, Kennedy then fired too, followed by a second discharge

from Michie. Michie and Kennedy then

stood for a while and deliberately recharged their weapons before turning and

making off uphill.

The constable,

John McIntosh was hit by the first shot about the knees and legs but continued

his pursuit. He said that Michie had deliberately

aimed at him. McIntosh was then hit

again, felt giddy and tumbled off his pony before crumpling to the floor. The pony was also hit by numerous pellets. Alexander McDonald, the Kindrogan keeper was

also struck and the wounds on his face bled profusely. He was also injured on the crown of his head,

his left hand, his right ear and right arm.

McDonald received wounds from six pellets in total, but his clothes were

“riddled”. The injuries rendered him

“stupid”, but he did not lose consciousness.

Rattray took Alexander

McDonald to a nearby house, but later McDonald managed to ride a pony into Kirkmichael

to get medical attention for his wounds.

The constable, John McIntosh was carried to the house of John McNab, a

farmer on the estate of Balnabroich, which was located about 60 – 100 yards

from the point where he fell and there the policeman recovered his senses. John Stewart was hit by the third discharge,

with two pellets striking on his right side, one of which lodged in his hip and

the other in his eyebrow, the wounds then bleeding, though they were, apparently,

not painful. John Murray, son of tenant

farmer Robert Murray, was also struck by pellets.

Another farm

servant, John Webster an illiterate who worked at Drumhead of Kilty was a late

follower of the posse and witnessed, at a distance, the shooting event. His evidence was dismissed by court officials

by the remark “This man is silly” but he did add the important information that

he knew both Michie and Kennedy well and that Michie had stayed with him “for

some time before that”.

There was a

further witness who joined the chase late.

He was Thomas Ferguson, the shepherd at Pitkermack. While tending his sheep, he heard shots fired

in Pitkermack wood. He then saw the

poachers cross the bridge with others in pursuit and joined the chase. But he was

some distance behind the main group of pursuers when the shooting

happened. He subsequently followed the

retreating poachers in the company of farmer Alexander Fraser for about a mile

up the Hill of Balnabroich. The poachers

were speaking to them, but Ferguson could not understand what was being

said. Importantly, he too knew the

identity of both the men he was pursuing.

One further addition to the chasing party was Thomas McGlashan, farmer

at Cultalonie but though he witnessed what happened at a distance he could not

add any information to that provided by the other witnesses. He too was illiterate and was dismissed by

court officials with “This witness cannot identify the prisoner. He is a very stupid witness at any rate”.

Henry Rattray

was adamant that the pursuers had not provoked the poachers to discharge their

guns and he did not hear the poachers give a warning that they were about to

fire before they pulled the triggers.

The whole incident was over before 12.00 noon. The Kindrogan keeper, Alexander McDonald was

carrying his gun during the pursuit, but he did not raise the gun or threaten

to use it against the poachers. Also, he

did not set his dog at the retreating men.

Dr James Kippen,

a surgeon from Kirkmichael was summoned between 12.00 and 1.00pm on Saturday 21st

December to go to John McNab’s house at Hill of Downie. There he examined and dressed the wounds of

the constable, John McIntosh, which were bleeding profusely, with blood over

his face, and his clothes generally saturated with blood. He was cold and faint. However, the farmhouse was very dark which

made the surgeon’s work difficult, so he ordered that McIntosh be taken home,

where he examined him again the following morning. The constable had been hit by 30 to 32

pellets of no. 5 shot. (Lead shot is

graded from 1 to 9, the higher the number, the smaller the shot and the less

damage would be caused by a single pellet.

No. 5 shot has a diameter of 2.8mm and a weight of 1.99g. This grade of shot would typically be used

for shooting birds the size of a pheasant and could also be used for shooting

rabbits and hares). Dr Kippen’s

assessment was that John McIntosh’s wounds had not endangered his life, though

he had some concern that fever might later manifest itself.

Two other

surgeons, Wm Malcolm and F Thomson from Perth examined John Murray at

Cultalonie on Monday 23rd December.

They found marks of small shot on his right thigh and right hip. This medical pair also examined John McIntosh

at the same venue. McIntosh was much

more seriously injured, receiving eleven pellets in his left leg, six in his

opposite leg, one below his right eye, three in his left breast, one in the

right side of the neck, two in the right forearm, one in the right arm, two in

the left arm, one in the stump of the left hand and one under the pectoral

muscle on the right side. He was clearly

unwell. His tongue was white, his pulse

small and rapid (97) and his skin was cool.

He was suffering general stiffness of his limbs especially his left knee

and he was afflicted by sleepless nights, headache and nausea.

On Monday 23rd

December, James Kippen also attended the gamekeeper, Alexander McDonald who had

been shot. He had four shot wounds about

his right eye, which had penetrated to the bone and caused substantial

bleeding. Kippen’s conclusion was that

he was not dangerously hurt. The same

day, Kippen also saw John Murray, son of tenant farmer Robert Murray. He had one shot wound in his right hip and

may have had a second wound in his ankle.

His injuries were thus minor.

This was a

serious incident and strenuous efforts were made to capture the errant pair but

to no avail. Some years later, the

Dundee Advertiser claimed that Michie, while on the run, had been “skulking

about occasionally making hair-breadth escapes from the officers who were, from

time-to-time, endeavouring to apprehend him”.

After the shooting, the poachers

had escaped over Balnabroich Hill in the direction of Blacklunans, a small

village on the Blackwater, just over the border in the neighbouring county of Forfarshire

(also known as Angus). Perhaps this

small settlement, where David Kinloch Michie’s illegitimate daughter, Lilias

and her mother Ann Stewart lived, provided a safe house for the fugitives. It is also possible that moving to Forfarshire

would provide some protection from the efforts of the Perthshire Constabulary

to detain the fugitives. Farm servant,

John Webster, who knew Michie, revealed that Michie had been staying with him

for “some time before that”, which suggests that there were friends and acquaintances

in the countryside who were not prepared to inform on the notorious poacher,

perhaps from a mixture of both fear and sympathy.

David Kinloch

Michie and Alexander Kennedy were indicted for discharging loaded firearms in

contravention of “the Statute tenth George the Fourth chapter thirty-eight” and

summoned to appear before the Circuit Court of Justiciary to be held at Perth

on 28th April 1840. Not

surprisingly, they did not appear, and the Court pronounced the pair to be

outlaws and fugitives from Her Majesty’s laws.

In consequence, “their whole moneyable goods and gear to be escheat and

inbrought for Her Majesty’s use”, though it is unclear if either man had much

in the way of property which was within the reach of the law. “Escheat” is a process by which goods and

property revert to the Crown.

Georgina,

Duchess of Bedford

At this point,

it is appropriate divert from David Kinloch Michie to give a brief summary of

the background of this lady, to show how she achieved her position of influence

and why she routinely spent half of each year living in Scotland on the

Rothiemurchus estate near the modern holiday resort of Aviemore, then a mere

village on the road to Inverness.

Georgina (or

Georgiana, a name variant she used from time to time, however, the “Georgina”

alternative is used consistently here) was born at Gordon Castle, Fochabers,

Morayshire in 1781. Her parents were

Alexander, 4th Duke of Gordon and Jane Maxwell who hailed from a

minor aristocratic family in Edinburgh. The

Gordons were one of the most powerful, wealthy and influential families in

Scotland. Jane, who was a charismatic

and unconventional lady, snared the country-loving Alexander at a ball held in

the Assembly Rooms in Edinburgh. The

couple married in 1767 and had a family of seven, two boys and five girls, the

last of which was Georgina. Her mother’s

main aim in life was to achieve good, ie aristocratic, marriages for all five

of her daughters, an objective which she achieved. After much manoeuvring, Georgina was

betrothed to a widower, John the 6th Duke of Bedford whose first wife,

Georgiana, had died after bearing three children. He was 15 years older than Georgina. Her mother, Jane, was delighted that at last

she had bagged a duke. The two were

married on 23 June 1803, when Georgina was 21.

Between 1804 and 1826, John 6th Duke of Bedford and his Duchess

and second wife, Georgina, had a family of 10 children. The Bedfords, too, were

exceedingly wealthy and had extensive estates in various counties including

Bedfordshire where the family seat, Woburn Abbey, was located.

Jane, Duchess of Gordon, was ill-matched to her country-loving husband. While he enjoyed shooting and fishing at Gordon Castle, she preferred the social life of Edinburgh and, subsequently, London, where she became a prominent figure in Tory social and cultural circles. This was ironic since the Bedfords were associated with the Whig party. Over time, the Gordons’ marriage gradually disintegrated.

Jane had a major influence on the development of Georgina who resembled her mother closely in personality. Due to Jane’s society life, Georgina became confident around the leading political and societal figures of the age. Her mother also taught her to love the country. Jane had established a rural retreat at Kinrara, a working farm in the upper Spey valley in the parish of Alvie. Georgina came to love the area and the simple life she led there. She would retain a life-long devotion to the area. Jane also brought up Georgina to be interested in the welfare of people at all levels in society, including the local poor.

The significance

that Kinrara held for her mother was recognised by her being buried there when

she died in 1812 and a monument was raised to her memory. Kinrara then passed to Jane’s brother George,

the Marquis of Huntly, but he only occupied the house for a short time each

shooting season to accommodate himself and his bachelor friends, otherwise it

was shut up. Georgina and her husband,

the 6th Duke of Bedford, turned their attention to the property of

Invereshie Lodge, located five miles further up the Spey valley in a raised

position at the confluence of the Spey and its tributary, the Feshie, as a

summer retreat. The property belonged to

the Macpherson-Grant family and in 1815 they acquired the extensive Forest of

Feshie, which they had previously only rented, from the Duke of Gordon. In 1818, the two Feshie properties were

combined to create a sporting estate of over 13,000 acres and it was leased for

many years by the 6th Duke of Bedford. The Invereshie property extended up both

sides of the Feshie, so Georgina could continue her simple country life in the

summer and autumn each year, including living amongst the local population in

small settlements high up the Feshie valley.

Edwin Landseer

(1802 – 1873), a precocious portrait painter, especially of animals, first

entered the life of the Bedfords in 1820, when he was 18 years old. The Duke of Bedford became his patron and

inevitably Landseer also came into contact with Georgina. He was 21 years her junior and only slightly

older than her eldest son. Landseer’s

first recorded visit to Woburn was in 1823.

He had been commissioned to paint a portrait of Georgina, so they

inevitably spent much time together and there was an instant attraction between

them. Subsequently, Landseer did many

sensitive paintings and sketches of her and acted as her art tutor. Landseer’s first visit to Scotland was in

1824. It is not known if Landseer

visited Georgina at this time, though she was staying at Invereshie, about five

miles south of Kinrara. There has been

much speculation on the nature of the relationship between Georgina and

Landseer. Of the two biographers of

Georgina, Rachel Trethewey believes that it was sexual and started between 1823

and 1825. On the other hand, Keir

Davidson is more cautious, due to a lack of direct evidence for the nature of

the relationship.

In 1822, the

Duke of Bedford suffered a severe stroke while he and Georgina were staying at

Endsleigh, his home near Tavistock, Devon, which caused Georgina much

distress. In 1825 Georgina became

pregnant and her last child, Rachel was born in 1826. Both Georgina and Landseer were in the

Highlands at the time the child must have been conceived, leaving open the

question of the girl’s parentage. In

1827, Georgina spent four months away from her husband at Invereshie, where she

was almost certainly visited by Landseer.

Georgina became pregnant for a final time in 1830 but the pregnancy

miscarried.

The Duke and

Duchess of Bedford continued to visit Invereshie annually until 1829, always in

the company of a shifting population of prominent guests, including Edwin

Landseer. However, Invereshie had one

deficiency which was problematic for the sportsmen, it lacked sufficiently

extensive grazing for the ponies used for travelling into the hills and for recovering

deer carcasses. This lack of pasture

land led the Bedfords to look for alternatives to Invereshie. Initially, the Duchess made enquiries about

the Kincraig estate, which was located close to beloved Kinrara. However, the solution to the problem came in

1828 when a property belonging to the Grant family on the other side of the

Spey from Kinrara became available. The

Doune was larger than Kinrara and enjoyed excellent grazing. Georgina and her husband then used the Doune

as their summer/autumn Highland retreat for many years, though Georgina had

frequent battles with the Grants over the extent of access she could enjoy at

the property. Invereshie was then taken

up by a succession of wealthy sportsmen.

Edward Ellice, MP, a close friend of Georgina, used Invereshie as his

base from 1833 and is thought to have taken a five year lease to the property

in 1834.

Georgina’s

sons, Lord Edward Russell, Lord Alexander Russell and Lord Cosmo Russell, were

particularly keen sportsmen and regular visitors to the Doune. Lord Alexander took over the running of the

Doune deer forest in 1839.

At this time,

Landseer was becoming increasingly famous for his art and was elected to the

Royal Academy in 1831. After Queen

Victoria came to the throne in 1837, Landseer soon became her favourite

artist. In 1836 Queen Victoria’s mother,

the Duchess of Kent, had commissioned Landseer to paint a portrait of Queen

Victoria’s dog, Dash, for a birthday present, which impressed the monarch both

with Landseer’s painting skill and with his personality. In January 1838 he stayed at Windsor Castle

to paint a portrait of the Queen on horseback and in 1840 he undertook to paint

a portrait of the Queen’s wedding to Prince Albert. Landseer was knighted in 1849 while staying

at Balmoral Castle. The famous animal

portraitist also developed good relations with Georgina’s wider family

including her husband, the Duke of Bedford.

Bedford was aware of a close relationship between the painter and his

wife but tolerated the situation. Landseer was a keen deer-stalker. The Duke and Landseer went out shooting

together and they also conversed about art.

In 1838, Edwin Landseer and his brother Charles provided the

illustrations for the book “Deer-stalking in the Forest of Atholl” by William

Scrope.

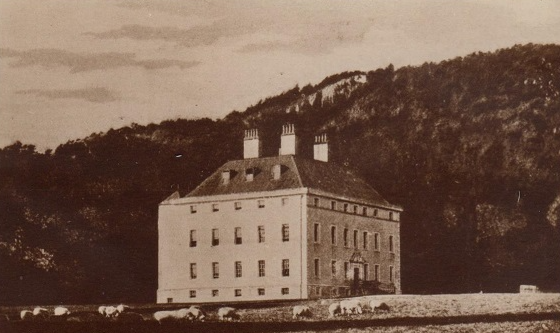

The Duke of

Bedford suffered a stroke while dressing on 17 October 1839 at the Doune,

Rothiemurchus. Local medical help was

called but he soon fell into a coma and expired on Sunday 20th. All the guests at the house left soon

afterwards. This event had a great

impact on Georgina because she loved her husband, notwithstanding her closeness

to Landseer. However, as the Dowager

Duchess, she was instantly demoted in societal eyes to a lower rank in the

social hierarchy and one which carried less influence. With the exception of her step-son Lord John

Russell, there was a rather distant relationship with the late duke’s first

family. It is claimed that in 1840,

Landseer proposed marriage to Georgina but that she turned him down, which did

not help his mental state. After that

year their relationship, though it was maintained, seemed to change in

character as the artist developed patrons elsewhere amongst the royalty,

nobility and aristocracy and spent less time in the company of the Dowager

Duchess.

In 1848, the

owner of the Doune, the recently widowed Lady Jane Grant, had returned from

India where her husband had been a judge, and wanted to reoccupy the

Doune. Georgina persuaded Lady Jane to

share the accommodation at the Doune, with the Grants moving out to Inverduie

House when the Dowager Duchess of Bedford wanted to stay in the Spey valley. Georgina died in early 1853 at Nice in the

South of France and had spent her last visit to the Doune in 1852.

David

Kinloch Michie on the run

According to

the “Weekly News” article, “Gow” shaved off his beard and repaired to Aberdeen

where he joined the police, presumably under an assumed identity, and was

instructed to look out for himself, a dangerous fugitive, described in a

warrant which was given to him. Then,

allegedly, during his duties, he became a familiar of “a widowed lady of high

rank” who was the proprietrix of a shooting lodge and estate and who invited

him to become her gamekeeper. This

caused him to confess his outlawed status to the lady, who was very influential

and she in turn “promised to do all she could to free “Gow” from the

consequences of his rash act”. A search

has thus been made of other information sources to seek independent evidence

which bears on these claims.

One fact of potentially

great significance is the employment of David Kinloch Michie’s brother, John,

as a gamekeeper in the parish of Alvie from at least 1836. In 1851 he was living in the property called

Pittourie but it is not known for how long this had been his abode. Further detail is provided by the lists,

published in various newspapers, of people who had paid for schedule D (land

occupier) and schedule B (gamekeeper) game certificates. In September 1843, John Michie had a schedule

B certificate provided by Lord Edward Russell (1805 – 1874), second son of

Georgina and Lord John Russell, over the lands of Kincraig. His brother, Lord Alexander, Georgina’s

youngest son, held a schedule D game certificate for the Doune in 1848.

John Michie’s

brother, David Kinloch, had been on the run since 21 December 1839 and was

formally declared an outlaw on 28 April 1840.

He was finally apprehended and taken into custody at the end of July

1845, probably on 28th of that month, the details of this event are

given below. Thus, David Kinloch Michie

was on the run for about 4 ½ years and the speculations made in my previous

article on this blogsite about him possibly joining the police after his trial

are simply wrong. If he joined a police

force and made the acquaintance of an influential widow, it must have been

between late 1839 and summer 1845.

One witness at

David Kinloch Michie’s trial in 1845, Angus McDonald, gamekeeper at Glen

Firnat, Mouline, Perthshire, recounted that he knew Michie from before the

shooting incident, meeting him about a year after he went on the run, ie about

December 1840, on McDonald’s grounds at Glen Firnat. David Kinloch Michie was in the company of

another poacher by the name of Dobson. McDonald

and Michie spoke about the shooting incident and Michie’s attitude to it (see

below). This evidence suggests that

David Kinloch Michie was still pursuing a poaching lifestyle about a year after

he absconded, further narrowing the period during which his alleged

interactions with the widow could have occurred.

The arrest

of David Kinloch Michie

Contemporary

newspaper reports credited Sergeant William Christie of the Perthshire County

Constabulary with the apprehension of David Kinloch Michie in Blairgowrie on 28

July 1845, 4 ½ years after he became a fugitive. At Michie’s subsequent trial, Christie gave a

detailed account of the process by which Michie was secured. It had some unusual features which require explanation.

A commendably

suspicious Sergeant Christie, up early in the morning in Blairgowrie for

another purpose, spotted three men, two of whom he knew to be William and

Alexander Michie, travelling in an easterly direction along the High Street,

past the end of Brown Street. He did not

know the third man but suspected at the time that he might be a notorious

poacher by the name of Sim. Christie

followed the group to the house of John Bance, a vintner, located in Allan

Street, and the trio went inside.

Christie entered, sat in the same room as his quarry and ordered a gill

(quarter of a pint) of whisky. Before

his glass of spirit arrived, Christie was offered a dram by William Michie,

which he accepted. (The formal

definition of a dram is 1/32 of a pint, but it is understood informally in

Scotland to mean a small glass of whisky).

While drinking the proffered glass, Christie noticed that William Michie

was winking at the man whom he thought was Sim, suggesting that they believed

that Christie did not know that one of their number was the fugitive, David

Kinloch Michie. This knowing gesture

made Christie suspicious that the man whose identity was unknown to him was, in

fact, the outlawed brother of William and Alexander Michie.

Christie then

asked William Michie, straight out, if the third member of their group was

David Kinloch Michie. He immediately stood

up and admitted his identity, “Yes, my name is David Michie, what have you to

say to me”. To confirm this identity,

Christie asked John Bance, on his return to the room with the policeman’s

whisky, if the third member of the group was David Michie. Bance replied in the affirmative. This must have been a difficult moment for

William Christie. He was being

confronted, not just by an outlawed, violent poacher but, additionally, by two

of his brothers, one of whom was also a seasoned law-breaker. Surely, David Kinloch Michie could easily

have made his escape, as he had done several times in the past five years, with

or without the help of his brothers, had he wished to do so? Does this imply that DK Michie had already

made up his mind to surrender?

Christie asked

David Michie to sit down as he had something to say to him and that he was an

outlaw. Although Christie did not have a

written warrant for DK Michie’s arrest, he did have an order to take him into

custody. David Kinloch Michie then

agreed to go with Sergeant Christie, but only on condition that he would not be

handcuffed and that he would be treated “like a gentleman”. Christie then asked William and Alexander

Michie for their help, should David Michie attack him, but agreed not to use

handcuffs or to call for additional policemen, if David acted peaceably. DK Michie agreed with Christie’s proposal,

surely confirming that he had indeed concluded that he should surrender. Christie further proposed that they should

leave Blairgowrie for Perth surreptitiously, so that the public remained

unaware of what was happening, otherwise a crowd might have been caused to

gather and could have led to a disturbance.

Again, DK Michie concurred with Christie’s suggestion.

So far, so

good, for William Christie’s plan to secure the outlawed poacher. But then he met an unexpected hurdle. He sent the vintner, John Bance, to get a

conveyance for the journey to Perth but he returned empty-handed. Christie, keeping a cool head, suggested they

should instead have some breakfast while they waited for the stagecoach. Again, David Michie assented to Christie’s

proposal. After the meal had been

completed and the group had had more whisky, there was still time to burn, so

Christie took the group to his own home to await the arrival of the

stagecoach. Then they all travelled

together to Perth, apparently without incident.

Although David

Kinloch Michie had, in effect, given himself up into Christie’s custody, in

other ways he remained defiant and uncooperative. He never mentioned the incident that had

caused him to be declared an outlaw, or admitted to his guilt to the charge of

wounding his pursuers. Also, he did not formally

surrender to Christie, or wait on him for that purpose. Once in the county town of Perth, David

Kinloch Michie made a declaration before Hugh Barclay, Sheriff Substitute for

Perthshire. That statement is given

below in full, as it is a masterpiece of obfuscation, masquerading as

cooperation. It is difficult to have

confidence that anything stated by DK Michie in the document is either accurate,

or at least nearly truthful. Perhaps

what it does underline is that David Michie was a very clever individual.

“Compeared

David Kinloch Michie who being duly cautioned and examined, declares that he is

a labourer and that he has not been residing in any fixed residence for

sometime back. That he does not

recollect whether he resided at Cowford in December 1839. That his father at that time resided at

Cowford. That he thinks he had left

Cowford before that time. That he was a

little acquainted with a person of the name of Alexander Kennedy but who was

better known by the name of Alexander Rannach.

That he never was on the moors with Kennedy, but he has been in his

company on the road. That he thinks he

has heard of a Moor called Balnabroich but he cannot say whether he ever was

upon it. That he did not know a person

of the name of Alexander McDonald, game keeper, Kindroggan. That he never was detected poaching on the

hills in the parish of Kirkmichael or on any hills in that district / country,

either by one or more persons. That he

did not in particular in that district of County, either in the years 1839 or

in 1840, or at any time, fire, or attempt to fire, at any persons with a

fowling piece, or with firearms of any kind.

That he never saw any charge against him for any offence whatever and

was not aware that any officers had been in search of him, and he is not aware

that he was outlawed at the Circuit Court at Perth for not appearing to answer

a charge for having shot at certain persons in the district of

Kirkmichael. That he is twenty-four

years of age. That he left his father’s

home when he was between the age of ten and fifteen and has not had any fixed

residence since that time, but he was in service for some time since his

leaving his father’s house. That during

the last five years the declarant has been working up and down throughout

Scotland and England and has frequently been in the neighbourhood of

Blairgowrie for short periods during that time.

That he came to Blairgowrie this morning from my father’s house at

Cowford. David K Michie. Hugh Barclay.

Thomas Duncan. JT Gibbons. H Martin”.

David Kinloch

Michie was held in Perth prison while he awaited trial.

The trials

of David Kinloch Michie

Immediately

after the arrest of DK Michie at the end of July 1845, the processes of law

swung into action in preparation for Michie’s appearance in court. Some of the witnesses (Alexander Fraser, then

tenant of Mains of Downie, and Henry Rattray, then farmer at Stronamuck)

revisited Balnabroich hill to remind themselves of the exact location of the

poachers and their pursuers when the shooting occurred. The surgeons who had treated the wounded gave

in reports of the injuries sustained, though the report from James Kippen, the

Kirkmichael surgeon, was disappointing.

He had not made notes at the time but claimed that he “remembered all

the circumstances perfectly”. Also in

early August, several witnesses from the chasing party were taken to Perth

prison to view the prisoner and confirm his identity. For some of the visitors the time interval

since the event and the relatively brief nature of the encounter led to some

uncertainty that the prisoner was Michie.

For example, John Murray, son of Robert Murray the farmer at Dalvie,

confessed “I have this day seen David Michie, but I cannot say that he is one

of said poachers or even like either of them”.

However, others had no doubts that DK Michie was the taller of the two

poachers on the fateful day. Alexander

McKenzie, overseer at the farm of Balmyle, was quite certain in his

identification. “I have this day seen

David Michie in Perth Prison”.

David Kinloch

Michie was accused of a contravention of the second section of the statute 10

Geo 4 Chap 38 and was first brought to court on Friday 10 October 1845 during

the Autumn Circuit at Perth. David

Michie’s counsel, Mr George Patton, then objected to the indictment on the

grounds that the locus delicti had not been sufficiently specified. “On

or near to the hill of Balnabroich in the parish of Kirkmichael and shire of

Perth” was held by the judges to be too vague, bearing in mind that the feature

in question was about two miles long by three miles wide. Before the close of the court the following

day, Mr Patton petitioned the sheriff, craving that Michie be released from

prison on bail, but this was refused. A

further application of a similar nature was made to the judges on the circuit,

who also declined to grant bail. These

results were not surprising, given the fact that Michie had been on the run for

nearly five years. David Michie was then

detained on a further warrant and consigned to Perth prison to await a new

trial.

This setback in the legal process prompted John McLean, Joint

Procurator Fiscal for Perth to visit the hill of Balnabroich with four of the

witnesses, Alexander

McDonald, John McIntosh, James Stewart and Alexander Fraser. All agreed that the name of the hill was

correct and that at the point where the poachers discharged their guns, the

ground belonged to Mrs Valentine Haggart under entail and the spot was located

about 200 yards further up the hill than the head dyke of the farm of

Balnabroich.

Meanwhile,

David Kinloch Michie continued to be held in Perth prison. Towards the end of

November 1845, he was again indicted and accused at the instance of Her

Majesty’s Advocate for Her Majesty’s interest of contravening second section of 10 Geo 4 Chap 38 and of assault by discharging a

loaded gun, causing the effusion of blood and serious injury of the

person. It is worth extracting the part

of this statute relating to the use of guns, because it clearly encompasses the

crime which was committed. “An Act for

the more effectual punishment of attempts to murder in certain cases in

Scotland, it is enacted by Section

Second That from and after the passing of this Act, if any person shall within

Scotland wilfully, mischievously and unlawfully shoot at any of His Majesty’s

subjects, or shall wilfully mischievously and unlawfully present point or level

any kind of loaded fire arms at any of His Majesty’s subjects, and attempt by

drawing a trigger, or in any other manner, to discharge the same at or against

his or their person or persons … with intent in so doing or by means thereof to

murder or to maim, disfigure or disable such His Majesty’s subject or subjects

or with intent to do some other grievous bodily harm to such His Majesty’s

subject or subjects … such person so offending, and being lawfully found guilty

actor or art and part of any one or more of the several offences wherein before

enumerated, shall be held guilty of a capital crime and shall receive

sentence of death accordingly”(author’s emphasis).

The case was

heard in the High Court, Edinburgh on Monday 15 December 1845, starting at

9.30am. Jurors, most of whom were farmers,

were notified of their obligation to attend for the trial, under threat of a

fine of 100 merks. The prosecution was

led by the Solicitor General, with the assistance of Mr David Milne AD and Mr

Charles Bailey AD. Michie continued to be

represented by Mr George Patton. David

Michie pleaded “not guilty” to the charges laid against him. The witnesses were those named in the

compound account given above on the progression of the events leading up to the

shooting, the shooting itself and its immediate aftermath. Some of the witnesses had moved on to new

positions by the time of the second trial.

It did not take

the jury long to find David Kinloch Michie guilty as charged but the Lord

Justices held over pronouncing sentence until Wednesday 17 December 1845 and,

in the meantime, Michie was remitted to Edinburgh prison. Two days after the trial, he learned his

fate, “to be transported beyond seas for the period of seven years from this

date and that under the visions and certifications contained in the Acts of

Parliament made there anent, and ordain him to be detained in the prison of

Edinburgh till removed for transportation”.

It has to be

concluded that Michie was a very lucky man not to receive a capital

sentence. Had he committed his offence

and been tried a few years earlier, or had he killed one of the pursuers, he

could easily have been condemned to death by hanging for his crime, bearing in

mind the evidence given by Angus McDonald, the Glen Firnat gamekeeper, who met

Michie by chance on the hill about a year after the shooting. “I entered into conversation with Michie and

asked him if he was not afraid to be going about there after what he had done

and more especially as he was an outlaw, and he said that he was not at all

afraid and that all Glenfirnat would not take him. I then asked him if he really aimed at

McDonald seeing that he had hit him in the face, to which he answered that he

had aimed at him and was sorry he had not killed him. I do not recollect what his grounds of

illwill at McDonald. I asked him if

he was not afraid that when he did fire, he would kill him and he said he was

not afraid of killing him but wished he had done so” (author’s emphasis).

The reason for

the lack of capital sentence was due to the actions of the reforming

politician, Lord John Russell, son of the 6th Duke of Bedford and

stepson of Georgina, the Duchess of Bedford.

In 1837, Lord John Russell steered a series of seven Acts through

Parliament which together lowered the number of offences carrying a sentence of

death from 37 to 16. This was reduced

further by the Substitution of Punishments of Death Act 1841. After these reforms, the death penalty was

rarely used in the UK for crimes other than murder. Lord John, a Whig, was famous for other

reforming political work. He supported

the pardon of the Tolpuddle Martyrs in 1836 and he was a major supporter of the

Reform Act of 1832. Transportation for

seven years was a frequently used sentence for many crimes in the 1840s. At the Glasgow Circuit Court held in May of

that year, 57 of the 116 cases resulted in that sentence. At the same session there was only one sentence

of death.

The link

between David Kinloch Michie and Georgina, Dowager Duchess of Bedford

Proof of a

connection between David Kinloch Michie, his brother John and the Dowager

Duchess of Bedford comes from game certificate lists of 1848 – 1851 for

Inverness-shire. In all these years the B

game certificates of the two gamekeeping brothers were provided by

Georgina. David for Rothiemurchus (1848)

and the Doune (1849, 1850, 1851), John for Kincraig (1848, 1851) and the Doune

(1849, 1850). It is likely that the two brothers

continued in her employment until her death in early 1853, after which they

sought alternative positions. Georgina’s

need for the services of a gamekeeper related to the country sports interests

of her sons and her many guests at the Doune, including Edwin Landseer.

So far, no direct

evidence has been uncovered for David Michie joining a police force. Presumably, it would have been the Inverness-shire

force, since the Duchess’ Scottish properties were all located in that county. But circumstantial evidence shows clearly

that this claim might be true. Lord John

Russell was responsible for introducing one further piece of legislation which

bears directly on this question. The

County Police Act of 1839 enabled JPs in England and Wales to establish police

forces in their counties. It was also

known as the Rural Police Act or the Rural Constabularies Act. Establishment of such forces was not

compulsory, so some counties then created police forces, but others sat on

their hands. Lord John Russell was Home

Secretary from 1835 to 1839. This

legislation did not apply to Scotland, but a similar Act was introduced there

in the Rural Police (Scotland) Act of 1839.

Police forces in Scotland finally became mandatory in 1857. The stimulus for the creation of police

forces was often due to problems caused by vagrancy, rural unrest and

industrial militancy. Commissioners of

Supply were responsible in Scotland for the formation and oversight of county

police forces and for raising money for these purposes by a tax on landed

property.

In 1840, an

advertisement appeared in the Inverness Courier for applicants to a new police

force for Inverness-shire.

“Inverness-shire Rural Police.

Applicants for situations of Sub-Inspectors and District Constables

under the Rural Police of this County are requested to lodge their applications

and testimonials with the Sheriff Clerk of the County on or before Thursday the

19th inst. Castle, Inverness,

9th November 1840”. The

Inverness-shire Rural Police Force first functioned in the financial year

starting in April 1841 but after a few years of operations, letters of

complaint started to appear in the local newspapers due to the cost of the service

and the perception that it was ineffective.

Sheep-stealing had nor decreased, and crime generally had increased, in

spite of the fact that a rural police constable lived close to his geographical

area of responsibility. Although perhaps

not directly relevant to DK Michie, Inverness-shire constable John McDonald was

involved in the capture of an outlaw by the name of Forbes who was hiding in a

hollowed-out peat stack at his father’s house in the parish of Alvie in October

1842.

Did a vacancy

in the Inverness-shire police for a district constable in the Alvie area become

known to David Kinloch Michie in the period 1840 – 1843, which he saw as a good

cover for his true identity? If so, what

was the significance of the employment of John Michie, David’s brother as a

keeper in the parish of Alvie, probably from at least 1836 and possibly by the

Russell family? John’s employment

appears to have preceded brother David’s engagement by the Dowager Duchess by as

much as nine years. Was John Michie’s

presence at Alvie, from at least June 1841, a magnet for David in his quest to

avoid detection, once he went on the run, in late December 1839? Alvie, the Doune, Kinrara, Invereshie and

Inverduie all lay in the south-east part of Invernessshire, but not far from

the boundaries of five other counties (Perthshire, Aberdeenshire, Banffshire,

Elginshire and Nairnshire) which, together with the mountainous terrain, may

have been an attractive feature in the mind of the fugitive, especially as a

cover for his escape, should his presence in the south of Inverness-shire be discovered? However, the fact that his third illegitimate

child was conceived about March 1843, probably at Blacklunans, suggests he may

still have been following the life of an outlawed poacher at that date. Another intriguing question is whether John

Michie was in some way the conduit by which his brother, David, became known to

the Dowager Duchess of Bedford.

No evidence has

been uncovered that David Michie was ever transported, let alone for a period

of seven years, or for the alleged actions of Georgina in gaining a pardon for

the notorious poacher. He was sentenced

on 17 December 1845 but had returned to normal civilian life under his own name

by mid-November 1848, just less than three years after he was sent down. Something must have happened in the period

1845 – 1848, which resulted in his sentence being commuted both in type and

length.

Georgina,

Dowager Duchess of Bedford died on 24 February 1853 at Nice in the South of

France, where she had gone to spend the winter hoping the climate would

ameliorate health problems with her lungs.

For the Michie brothers, John and David Kinloch, it was now time to find

new positions of employment.

Employment

of David Kinloch Michie after working for the Dowager Duchess of Bedford

William Michie

has not been found in the 1851 census. A

William Michie, described as a labourer from Blairgowrie, was detected poaching

in a gang of four at Montreathmont Muir, near Brechin, Forfarshire, part of the

Earl of South Esk’s estate, in 1858. Two

men were detained but Michie escaped. In

1861, William was a gamekeeper working at Kirkmichael, Perthshire. He died of heart disease at Blairgowrie in

1870.

At the 1851

Census, John Michie was found living at Pitourie, Alvie with his wife,

Charlotte and six children. However, a

decade later, he had moved to England and found employment as a gamekeeper at

Hepburn, Northumberland, possibly in the service of Charles Bennet, the 6th

Earl of Tankerville, whose seat was at Chillingham Castle and who was a major

landowner in the area. John Michie

remained in this district for the rest of his life, dying at Chillingham in

1900. Tankerville was an occasional

visitor to Speyside, a friend of Landseer and may have known John Michie before

employing him.

Alexander Michie, David Kinloch Michie’s youngest brother, had been a farm servant at Cowford, as recorded in the census returns of 1851, but by 1854 he was employed as a gamekeeper by Roger James Robertson Aytoun, Esquire, at Ashintully Castle, Kirkmichael, Perthshire and continued in Mr Aytoun’s employment until at least 1857. Roger Aytoun had been a captain in the Fife Militia Artillery. At the census of 1861, Alexander’s employment had changed, and he was then a gamekeeper living at the Gamekeeper’s Lodge, Minnigaff, Kirkudbright. He died in 1888 at Perth.

In April 1852, David Kinloch Michie had married Ann Gilmore at Byth, King Edward, Aberdeenshire. The first child of this couple, John, was born in 1853 at Fetteresso, Kincardineshire, though it is uncertain who DK Michie’s employer was at this time. However, in 1854 and 1855, David Michie’s game certificate B was sponsored by Major Andrew Gammell, Esquire, of Drumtochty Castle, Forfarshire, over lands at Drumtochty. This village lies 10 miles south-west of Fetteresso. The Gammell family had made their money from banking in Greenock. By 1857, the Michie family had moved to Port Elphinstone, Inverurie, Aberdeenshire. David Michie was still employed as a gamekeeper, but his new master has not been discovered. This period of work seems to have been short-lived as by June of the following year David Michie had moved to the employment of the Duke of Gordon at Gordon Castle, Fochabers. His deployment as a gamekeeper at Gordon Castle was maintained until at least 1861.

By April 1863,

David Kinloch Michie had changed to a gamekeeping position at Levens Hall, near

Kendal, Westmorland, then in the ownership of Lady Mary Howard, a member of the

Bagot family, but occupied at the time by Mr W Wilson. Ironically, in 1863, David Michie was

responsible for laying an ambush for poachers on the estate, three of whom were

captured and put on trial. Michie

continued as gamekeeper at Levens Hall until at least 1867, though local school

records show that his children had two extended periods of absence, which may

indicate their father’s temporary removal to a new location. Also in 1867, David Michie is known to have

been breeding and selling retriever dogs.

In 1887, he was also breeding Fox Terriers. Several of his sons became noted game dog breeders.

David Kinloch

Michie returned to Scotland by 1871, where in the census of that year he was

found living at "Ashintully Gamekeeper's", Kirkmichael, the very

location occupied by his brother Alexander between about 1854 and 1857. However, he appears not to have been working

as a gamekeeper, since his calling was given as “hotel keeper”. By 1876, when David Michie had reached the

age of 56, he had become a farmer, at the property of Clunskea, Moulin,

Perthshire, located about ten miles by road west of Kirkmichael. The timing of this move into farming is known

from a newspaper report of him suing, successfully, a neighbouring farmer,

Alexander Cameron of Tarvie, for allowing his sheep to stray onto, and feed

off, Michie’s land. This was another

irony in the evolution of the outlawed poacher into a law-abiding citizen

willing to use the courts to maintain his rights. The 1881 Census gives some information on the

make-up of Clunskea farm. It extended to

1500 acres of which 25 acres were arable, so for a hill farm, it was quite

modest in size.

By 1882, David

Michie must have accumulated some capital since in that year he was able to buy

a parcel of 9 acres of development land on the edge of Montrose,

Forfarshire. His successful building out

of this property has been dealt with previously.

The teacher at

Levens school, which was attended by David Michie’s children, at least between

1863 and 1867, was George Stabler who became a noted naturalist. He established an enduring relationship with

David Michie’s eldest son, John, who was born in 1853. In 1880, John Michie was appointed as

forester to Queen Victoria on the Balmoral estates. Later, in 1901, he was promoted to factor on

the estates. George Stabler and John

Michie kept up a correspondence, mostly on nature matters, and Stabler visited

Balmoral twice on moss collecting expeditions in 1884 and 1894. Also in 1884, at the age of 64, David Kinloch

Michie walked from Clunskea to Balmoral to visit his son, John, travelling via

Glen Beg. The distance was about 40

miles cross-country. David had clearly

maintained his fitness.

The two-part biography of John Michie

(1853) can be found on this blogsite. It

borrows heavily from diaries kept by the royal servant during his years at

Balmoral. Although he must have been

aware of his father’s dramatic career as a poacher, he never mentioned elements

of that story directly in his account of his own life. Perhaps he kept his father’s dodgy past a

secret in case it should have an impact on his own prominent position? But

there was one story which appeared to refer obliquely to his father’s past

activities. The diary entry for 4 August

1891 is as follows. “Organized a party

for a drive to Dunkeld. It consisted of

the old people, Augusta & Neilson & boy, (sister & her husband)

Duncan McLean, and Helen & myself.

We drove by the Loch of Cluny where all crossed by boat and had a look

through the old castle on the island.

The district round here being the scene of my father's boyhood he was

eminently in a position to describe it, which he did minutely”. Adjacent to the southern end of this loch

were the lime works which had been managed by DK Michie’s father. But perhaps more meaningfully, the area lay

within the compass of David’s notorious poaching activities.

At the time of the 1891 Census, David

Michie had retired from farming and was living in Blairgowrie, where he

remained for the rest of his life. David

Kinloch Michie then continued on his reformed path of upright, law-abiding

citizen, acting as guarantor for a school inspector to the tune of £200 in

1893, attending the local Highland Gathering, developing his property at

Redfield, Montrose, and finding time to sue a firm of painters and decorators

for shoddy work. He died at 18 Perth

Street, Blairgowrie on 26 February 1893.

At that time, the value of his moveable estate was £586. David was buried in the local cemetery and,

even today, his grave is neatly maintained by someone, possibly a local

resident, who perhaps knows of his exploits, both legal and illegal and,

perhaps, feels that his memory in his adopted town should be kept alive.

What has been added and what remains to

be done

The present investigation has

undoubtedly strengthened the claim that the identity of “Donald Gow” in the

1904 article in “Weekly News” is David Kinloch Michie (1820 – 1903), that the

story represents real events from his life and that some of the details of his

life, deliberately obscured in the article, have been clarified. In particular, the identity of the

influential widowed lady who persuaded him to surrender is now clearly

established as Georgina, the Dowager Duchess of Bedford, whose gamekeeper DK

Michie became. The area where his

interactions with her occurred is now clearly seen to be the upper Spey

Valley. Circumstantial evidence shows

that David Michie could have joined the Inverness-shire Rural Police and served

in that area. The details of David

Michie’s notorious shooting incident have been revealed in the trial papers

from 1845. Other information concerning

the actions of David Michie and his brothers illustrates a family that easily

crossed the boundary between gamekeeping and game-stealing over two decades,

and also the way in which support networks functioned to make professional

poaching profitable.

Not all events in the “Weekly News”

article have been supported by the revelation of new and independent

facts. The identity of “brother William”

as Charles Michie, who lost several fingers of his left hand to an exploding

gun has not been directly verified. No

information has been uncovered regarding the claim that Michie humiliated a solitary keeper by making him carry the poacher’s bag. Similarly, with the tale of Michie shooting

out a candle in a public house to prevent a poaching colleague getting drunk

before an expedition, no new evidence has emerged. Another pub story

of Michie’s bravado in evading capture after being found drinking also remains

in the unproven category. No direct

proof has been uncovered of Michie joining the police, or of his interactions, as a

police officer, with the Dowager Duchess of Bedford. Further, no direct evidence has so far been

discovered of Georgina’s intercession on his behalf with the legal authorities.

Interestingly, evidence has emerged

which could point to the process by which DK Michie might have joined the

Inverness-shire police, sought a rural posting in the upper Spey valley and

made the acquaintance of the Dowager Duchess and her shooting guests, and that

is the discovery that his brother John had been working as a gamekeeper in the

area since at least 1836, before DK Michie’s crime was committed, and that John,

too, was sometimes an employee of the Bedfords.

A tentative DK Michie chronology

It is now also possible to present a

tentative chronology for the main events of David Michie’s life to the point

where he had ceased to be an outlaw, had had his sentence commuted and had been

appointed as gamekeeper to the Dowager Duchess of Bedford.

183? – David Michie became a

professional poacher.

19 December 1839 – David Michie and

Alexander Kennedy seen poaching on Kindrogan land near Kirkmichael.

21 December 1839 – Michie and Kennedy

pursued by posse of locals, who tried to detain them, to the Hill of

Balnabroich. Both poachers discharged

their shotguns injuring several of the following party. Michie and Kennedy escaped and went on the

run.

28 April 1840 – Michie and Kennedy failed

to attend court when summonsed, were declared outlaws and their moneyable goods

seized for the Crown.

December 1840 - Meeting in Glen Firnat