Introduction

Benjamin Ottewell, or “Uncle Ben” as he seems to have been almost

universally known, was a prominent landscape painter in watercolours in the

late 19th and early 20th centuries. After an apparently chance encounter with

Queen Victoria on the Balmoral estate in 1894, he caught her interest in his

art and estimated he sold “upwards of 130 drawings” to the Monarch over many

years. But Ottewell’s reputation does

not today enjoy high status in the art world.

When his pictures are offered for sale at auction, they generally

command prices in the region of £200 - £400, small beer even in the national

art market. It has to be said that Ottewell’s

claim to fame was influenced by his association with the Queen. But among those who know the striking scenery

of Upper Deeside, Aberdeenshire, there is an acknowledgement that Ottewell skilfully

caught the essence of this landscape, which juxtaposes mountains holding snow

for more than six months of the year, rushing rivers and forests of majestic

Scots pines, with a scattering of birch trees.

Queen Victoria was deeply attached to this land and its people, so it

should not be surprising that she patronised Benjamin Ottewell so extensively.

But what of the man himself?

What drove him to become an artist and to work so frequently in

Scotland, despite being born close to London?

What kind of personality did he possess and what moved him in life? Benjamin Ottewell wrote an autobiography

anonymously, which must be a very rare occurrence. “Some Trivial Recollections of an Old

Landscape Painter” was published in 1913 but, because he deliberately set out

to obscure dates, places and the identities of the people in his life, the

answers to many of the questions that the curious might pose, are not found, at

least directly, between its covers. The

book does not provide the fine grain description of his life that the enquirer

seeks. Indeed, it confirms that the man was

an enigma and intended to remain so.

While he was painting on Queen Victoria’s Balmoral estate,

Benjamin Ottewell encountered John Michie, then the head forester (1880 – 1902)

but later the factor (1902 – 1919) on the Deeside Royal holdings. Ottewell was clearly very personable,

humorous and a good conversationalist.

He became a regular visitor and guest in the Michie household. John Michie kept a diary, which detailed the

developing friendship between the two men and the role that Michie played in

bringing Ottewell’s works to the notice of Queen Victoria.

In “An annotated Bibliography of British Autobiographies”, William

Matthews, the author, described Ottewell’s literary efforts as “Notes on art

and painters; public events in England and Scotland; superficial (this author’s

emphasis) and genial jottings.” But

that is hardly an informed view. This

biographical work is not superficial but obscure and cryptic. It can only be seen as trivial by the uninformed. With persistence in mapping other, dated and

attributed, sources to the biography, much can be uncovered concerning Ottewell

the man and the events, some dramatic, to which he was party. This is the story of Benjamin John Ottewell’s

life.

The Ottewell family

Benjamin Ottewell was the son of William Ottewell, who was born in

1798 at Hadleigh in Suffolk. Ottewell

senior was married twice and with each wife he produced a large family. His first wife, Elizabeth Radcliffe, also

originated in Hadleigh and bore her husband at least nine children between 1821

and 1839, the first six of whom also saw the light of day for the first time in

Hadleigh. Before August 1836, the family

had moved to the Camberwell – Peckham area, now in suburban South London, where

Elizabeth died in August 1840. Less than

a year later, in February 1841, William Ottewell married again, this time to Ann

Pope, whose family hailed from Deptford in Kent. All eight, known offspring of this second

marriage were born in Streatham, about three miles south west of Camberwell and

Peckham. One of the two Ottewell

clutches must have had a child that was born and died between censuses and was

thus not recorded in these decadal population records, the two families containing

18 children in total. At the 1841

Census, William was described as a servant and his wife as a dressmaker. A decade later, William Ottewell was recorded

as a gentleman’s coachman, still living in Streatham, where he may have been a servant

for a wealthy builder in Leigham Lane.

Benjamin John Ottewell was the fifth child of his father’s second

marriage and Ben was born on 11 September 1847.

Curiously, he was not baptised until 28 May 1855, at St Leonard’s

church, Streatham (Church of England), when he was in his eighth year. Even more curious was the fact that the

Ottewells held a mass baptism on that date for five of their children, the

oldest of which, Edward George, was 12!

William and Ann Ottewell

Early development - a curious mind

Ben Ottewell’s childhood was described in general terms in his

autobiography, though with dates, names and places usually being omitted. He wrote, “My boyhood passed delightfully in

the southern shire (Surrey) in which I was born.” However, early on, his musing about his name

and birth date led him to conclude some “facts” which predicted his destiny. His birth date – in numbers – was 11/9/1847

and his full name was Benjamin John Ottewell, which contained precisely 20

letters. Benjamin “discovered” a series

of links between the two, 11+9 (date and month of birth)=20 (total letters in

name), 1+8 (first two digits of year of birth)=9 (month of birth), 4+7 (second

two digits of year of birth)=11 (date of birth) and 1+8+4+7 (digits of year of

birth)=20 (total letter in name). The

fertile mind of the young Ben concluded from these associations, by some quirk

of youthful logic, that he must be destined for fame and that, if this outcome

was fixed, he did not need to work! He

certainly thought that he was “lucky” from the occurrence of a series of

beneficial events later in his life. Ben

recorded that he was successful at shirking school, at devoting his time to

following the hounds on foot and at doing “a little poaching”. His childhood development was also hampered

by a serious illness, though the nature of the condition and the year that it

struck are not known. He was clearly

highly intelligent but wayward, lazy and of an independent bent. It was only at the age of 10, in 1857, that

he learned the alphabet and acquiring the skills of reading and writing. He also came to understand musical notation at

this time. These achievements were only gained due to the goading of his

younger sisters, who had overtaken him in academic status. By his own admission, he did not display

precocious talent.

Another unusual aspect of Benjamin Ottewell’s early life was the

frequency with which he discovered human corpses during his peregrinations. These deaths, at least four, were mostly the

result of suicide. “I found ‘em in the

water, by the side of the road, in a brewery yard, and in a hollow tree. Young and old of both sexes hanged and

drowned and shot.” These experiences,

which many young people would have found emotionally upsetting, did not seem to

perturb Benjamin, especially since he was paid half a crown expenses (about

£12.50 in 2018 money) for appearing as a witness at inquests!

William Ottewell, Benjamin’s father, had a relaxed attitude to

life, which must have contributed to young Ben’s lack of academic

progress. Benjamin described his father

as being “an easy-going old soul with scant sympathy for modern educational

crazes.” “He rode straight, shot

straight, loved strong ale and one good cigar after dinner.” However, the family must have shown some

concern for Ben’s lack of scholastic merit for, about the age of 12 (1859) he

was sent to a grammar school, “a few miles distant”. It is not clear if the family was still

resident in Streatham but, by the 1861 Census day (7 April), they were living

at Thorney House, Iver, Buckinghamshire, where William had apparently obtained

a new position, though still as a coachman.

Formal and informal education

Benjamin’s move to grammar school was a disaster. The headmaster had been warned in advance of his

lack of educational achievement and the standard approach to backward pupils

awaited Ben’s arrival. In those days scholars

who failed to learn quickly were brutalised, both physically and emotionally

and this approach was immediately applied to the new attendee. On the first day, he was required to read a

sentence out loud to the class and made a mess of the pronunciation, which

caused his classmates to laugh. His

teacher persevered by making him repeat the exercise, finally forcing Ben to

declaim standing on a form. His mistakes

were rewarded by his teacher boxing him around the ears. A defiant and angry Benjamin responded by

punching the teacher on the nose. This

rebellion against authority had its inevitable consequence. Ben was beaten with a cane by the headmaster

and sent to solitary confinement, without tea or supper. The rebel ran away during the following night,

found his way home and never went back to the school. During the early 1860s there was little

advance in Benjamin Ottewell’s formal education. However, about the age of 17 (1864 – 1865) he

was sent for a year to a Non-Conformist College for Schoolmasters, whose principal

was a Dr Talbot. Benjamin was by that

time reading novels and “anything he could get his hands on”. He was

also good at poaching and enjoyed playing practical jokes.

Sport and music

In the sporting arena, Benjamin had become a skilful cricketer,

describing himself as a “slogger and a fast bowler”. He particularly enjoyed the sociable aspects

of the game, with competing teams dining with each other after a match, smoking

cigars or pipes and having a good sing-song.

By 1869 Ottewell’s cricketing skills were good enough for him to be

selected for the Surrey Colts and on the 13 and 14 September he played for East

Surrey against West Surrey. Ben was a

sporting all-rounder, participating in golf, football, cricket and tennis, in

addition to wielding the willow. His

approach to life at this time appeared to be focussed on having fun and not on

gaining formal qualifications, which might have been beneficial for routine employment. Another activity which gave him joy was

taking part in glees, madrigals and part-songs, which he looked upon as healthy

exercise. Later, possibly after his

illness, he also took up billiards and betting on horse races, “… anything in

fact that wasn’t considered respectable in our Nonconformist household”!

Employment and cricket

About 1866, Benjamin Ottewell was obliged to seek employment and

“drifted” into the Civil Service, ruining his chances of doing the job he most

wanted, which was to play cricket professionally. Ben was not impressed by his new employment

situation. “Here followed the most

tiresome and unsatisfactory years of my life!

Seven long years (to about 1873) of playing at work in an

over-manned, over-paid office where the most strenuous job of the year was

getting up the Derby “Sweep”.”

By late 1869 Benjamin’s father, William, appeared to have retired

and the family had moved to live in Wimbledon.

In April 1871 William Ottewell, of no stated occupation, was living at

Montague House St Mary, Montague Road, Wimbledon with his wife Ann and four of

his children. Benjamin, one of the children at home, was at this date in work

as a temporary clerk in the Civil Service. William Ottewell died in September

1871 and at least two of his surviving offspring, Benjamin and Edward, then moved

again, to Mentmore Villas, Griffiths Road, New Wimbledon.

In the early 1870s Ben Ottewell played cricket for the Clarendon

club, whose opponents included teams from Merton, Putney, Windsor and Eton, and

Mitcham. Benjamin was a competent

batsman and bowler. In 1872 he was the

club’s deputy captain and at the 4th annual dinner held in March

1873 at the White Hart Tavern, Merton, he received the President’s presentation

bat for the highest aggregate score.

Ill-health then intervened to end his cricketing career. The last newspaper report of his cricketing

exploits was in August 1873. Ben

suffered a bad bout of rheumatic fever in what was also his last year as a

clerk in the Civil Service. Ottewell

appears to have maintained his links with the cricketing community since in

December 1888 he attended a smoking concert inaugurating the next season’s

activities at the Clyde Cricket and Football Clubs, which was held at the

Anchor restaurant, Cheapside. There was

a long programme of entertainment after dinner “including several songs given

by Mr Ottewell”. Although no longer an

active cricketer, Benjamin would have been in his element at this event.

Entry into the world of art

With sport ruled out for the present, Benjamin sought an

alternative diversion – painting. “I

bethought me of the painting and unearthed the old crayons and the colour box (presumably

possessions he had had since childhood).

I read books on art, especially anatomy, Fau, Flaxman, Bonomi and the

rest of ‘em and later on bought shilling books on painting, Aaron Penley, NE

Green, and Barnard, besides Hill’s “Studies of Animals and Rustic

Figures.” I haunted a certain

second-hand bookshop in Knightsbridge and bargained for prints and lithographs

of cattle and sheep – principally by Sidney Cooper – and made large copies of

them in black and white chalk on tinted paper.

Then came the hiring at 1a 6d a week of chromolithographs after Birket

Foster to be copied in water colours and raffled for by fellows at the office

at ten shillings a time!” So, Ben’s

conversion to artist, induced by rheumatic fever, must have occurred quite

quickly, while he was still in Civil Service employment and at the rather late

age of about 26. But, like sporting

activities involving hand-eye coordination, Benjamin Ottewell proved to be

naturally talented as an artist. “And

this was the sum total of the instruction I received for the most arduous and

uncertain of all the entertaining professions!”

According to his autobiography, Benjamin John Ottewell never attended

Art School, even on a part-time basis.

However, according to an entry in Who’s Who (which was presumably

publishing data supplied by Benjamin), he studied for seven years at the

“Science and Art Department, South Kensington”.

This was a teaching establishment set up by the Government to promote

education in art, science, technology and design. Eventually, it evolved into the Royal College

of Art, probably the capital’s most prestigious college of art and design

today. It is not clear if Benjamin

Ottewell’s attendance at the Science and

Art Department was formal or informal, part time or full-time, but almost

certainly not the latter. This apparent

inconsistency over his artistic education seems to be part of the ambiguity and

obfuscation that Benjamin Ottewell cultivated.

At the time of his initiation into art, Benjamin was the only male

left in the family home. The pursuit of

his new-found calling, partly fuelled by obsession and partly by the necessity

of gaining an income, often led to penury as available money was spent on painting

materials in preference to food. “My

time was all my own now and was spent in making sketches in water

colours.” His subjects were mostly

landscapes and he enjoyed almost instant success. “… I had sold my first four water colours for

10s each (about £53 in 2018 money) and so satisfied was the purchaser

that he came next day and bought all I had – thirteen all told at a slightly

increased rate of 12s 6d each (about £67 in 2018 money). He had many more during the ensuing year and

was the means of my getting some small commissions; indeed, within the year it

was no uncommon thing to get four or five guineas (up to £590 in 2018 money)

for a drawing.” The earliest paintings

identified as by Benjamin Ottewell date from 1879.

Health problems again intervened in the form of a further attack

of rheumatic fever, “which kept me helpless for fourteen weeks and left me so

weak that I was unable to make any sketches and studies to be worked up during

the winter.” Forced inactivity resulted

in a debt of £80 (about £8500 in 2018 money) being accumulated. But debt

coerced him into overcoming his natural disinclination to work. As an

alternative to developing outdoor sketches he turned to creating paintings of

potted plants “all that winter and spring”.

“I hired pots of blooming plants and painted them, flowerpots and all

and sold them, the last batch going to a dealer who gave me 30s each (about

£160 in 2018 money) for them and a tip for the Derby!” Benjamin, being a

horse racing devotee, probably laid money on the Classic entrant, which

promptly lost.

At the 1881 Census, held on the night of 3rd April,

Anne Ottewell (widow of William Ottewell) was a 67-year-old lady living at 1

Martin's Villas, Wimbledon. Several of

her offspring were in the house with her, Hannah E Ottewell, Emily A Guile (now

married) with her daughter Lilly E Guile, Ellen E Ottewell and Benjamin J

Ottewell. The three young women were all

dressmakers. Benjamin, now 34, was

described as an Artist - Landscape painter.

Anne Ottewell died at Wimbledon in June 1884.

Art societies and exhibitions

In the years after first taking up painting, Benjamin Ottewell

took part in many field trips into the countryside of Southern England, often

in the company of fellow watercolourists.

However, his accounts of this time slot appear to be mixed up and do not

follow a lineal sequence. Early in the

1870s, while he was still playing cricket, he journeyed into his native Surrey

(including Shalford and Godalming on the River Wey), parts of Kent (Rochester

Castle) and Sussex. He specifically

mentioned Kitvale, on the Rother, Sussex, as one destination and Ecclesbourne

Glen, Hastings as another. Devon was a

more distant location for his studies, again fairly early in his painting

career. Devonian locations included the

environs of Exeter, with the towers of the cathedral visible in the distance,

Budleigh Salterton, where he did many sketches from the cliff tops, the beach

and in the Otter Valley, which resulted in him being chased by a bull. Hampshire was a further county which Benjamin

explored. There his locations included

“near” Laverstoke “where they make the paper for Bank of England notes”. This would have been Laverstoke Mill in the

Test Valley. Also, the Itchen and Avon

valleys. Another painting site in this

general area was Freefolk near Whitchurch.

Between leaving the Civil Service about 1873 and his success at

the Royal Academy in 1884, Ottewell’s autobiography infuriatingly leaves no

clues as to the timing of events during this 11-year period, which shaped his

successful entry into the world of public art.

However, a period of seven years of study in South Kensington would fit

into the interval comfortably. Ottewell

also claimed that he served on the staff of the British Commission to the Paris

Exhibition of 1878, which is likely to have been as a result of contacts made

at the Science and Art Department.

The Paris Exhibition of 1878 was an attempt by the French Third

Republic to re-establish the standing of the country after the humiliation of

defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 – 1871 and the subsequent deposition

and exile of Napoleon III and his Empress, Eugenie. The exhibition was mounted on a massive scale

in Central Paris and showcased French arts and manufactures to an international

audience, in addition to presenting contributions from many other nations,

including Great Britain. Prince Albert

Edward, Queen Victoria’s eldest son was president of the Royal Commission

controlling British participation in Paris, but it is unlikely that Ottewell

became known to the Royal family at this time.

Ottewell claimed that he became a landscape artist in 1878 but

this looks inaccurate, since he had been making and selling paintings, some of

which were certainly landscapes, since at least 1873. However, it is true that the earliest signed

paintings which are known to have been on public display date from 1879. Commercial success caused Benjamin Ottewell

to think of entering his work in exhibitions mounted by the established

artists’ societies and he was successful if having a “small watercolour”

accepted at the Society of British Artists.

This was a work called “The Clunie near Braemar and shows that he had

already started to travel to Scotland (see below) by 1884. (The SBA, now RSBA, was established in 1823

as an alternative to the Royal Academy.)

However, seeing his work on public display engendered some self-doubt

about the quality of his work. Nevertheless,

he pressed on but then had a submission rejected by the Royal Academy. “Then the luck changed again and there came a

time when I was hung at the RA (on the line too) the Institute of Painters in

Water Colours and the Grosvenor Gallery – all in the same year. Sold them all too…”. This year of growing acceptance in

professional art circles was probably 1885.

Benjamin clearly entertained the notion that public recognition would

bring higher prices in its wake but this expectation, sadly, proved to be wide

of the mark.

In total, the following galleries are known to have exhibited the

paintings of Benjamin John Ottewell. The

Grosvenor Gallery (three to

1900), the New Gallery (nine to

1900), the Royal Academy of Arts (four to 1900), the Royal Society of British Artists (one to 1900), the Royal Hibernian Academy, the Royal Institute of Painters in Water

Colours (four to 1900) and the

Walker Art Gallery. More locally, he exhibited at the Wimbledon

Art and Benevolent Society annual exhibition both in 1881 and in 1884. One of his

pictures “Russet Morn” was displayed at the Crystal Palace in 1885. It was described in the press as having

“commendable qualities”. Once Benjamin

Ottewell started travelling to Upper Deeside (see below) to paint, his pictures

were displayed at events in Braemar on several occasions. In 1891 he contributed “The

Callater Burn in Spate” and “Evergreen Pine” to an

exhibition in the Aberdeenshire village, along with other artists of sufficient

status to have had works accepted by the Royal Academy.

Benjamin John Ottewell worked mostly in watercolours, a medium

which lends itself to the speedy completion of a work and he was prolific. It appears that only one limited attempt has

been made to catalogue his total oeuvre.

Some works are owned by museums and galleries and six still reside in

the Royal Collection, but many more pictures appear to be in private hands and

have never been on public display. Such

artistic productivity would normally leave a trail of information which would

allow the aspiring biographer to trace the artist’s movements in time and

space. But Ottewell frequently

frustrates such efforts by recording the year of production of a work, but not

its location, or giving a painting a title, which is without value in

determining the location being portrayed.

Examples of this frustrating tendency are “Cattle by an Estuary”,

“Pastoral” and “River Scene”, but there are many, many more!

In 1895 Ottewell was elected an honorary member of the Royal

Institute of Painters in Watercolour.

This year corresponds precisely with the beginning of his association

with Queen Victoria and it is to be wondered if the monarch was influential,

either directly or indirectly in the granting of such official

recognition. Why was this an honorary

membership (ie based upon established status) rather than a regular

membership? There were 54 such elections

between 1893 and 1905, roughly four per year.

Of the 54 only three were honorary.

Ottewell was in very rare company!

Autobiography and character

The autobiography written by Benjamin Ottewell is very informative

about his general character and interests.

Above all else, he was a pleasure-seeker and enjoyed life in all its

aspects. Perhaps his most guilty

pass-time was smoking his pipe, because he admitted that he indulged in the

weed too much. He also enjoyed the

company of others, yarning, especially over beer and smokes and it was his

story-telling which led to the generation of “Some Trivial

Recollections of an Old Landscape Painter”.

The book was published in 1913, so the events described must antecede

that date. Ottewell described the occasion

which led to him undertaking the work.

“Written at the request of a lady to whom I had been spinning yarns in

the lounge of a Scotch hotel a few years ago”.

He also added the information that the lady was his niece, six years his

senior (implying a birth year of about 1841) and that her husband was a

publisher. She was the reason that he

acquired the sobriquet “Uncle Ben”. If

this description is accurate, she must have been the child of one of his

half-siblings from his father’s first marriage.

But here lies a problem, as there is no obvious candidate for his niece

in the family genealogy, as presently understood and the claim remains a

mystery. What is clear is that Benjamin

must have been an entertaining raconteur and that is largely how the book was

written, as a series of amusing anecdotes, mostly relating his own experiences

but sometimes retelling stories originating with his friends. It is alleged that Benjamin Ottewell wrote a

second autobiographical work, entitled “Loiterers all”, published in 1926. No copy of this work has yet been uncovered

in any public library or on offer from any second-hand book seller.

The Savage Club

Many of Benjamin Ottewell’s friends were fellow painters and some

of them accompanied him on his forays into the countryside. His membership of the Savage Club is also

indicative of the type of company that he enjoyed. This London club, founded in 1857 and still

in existence, was the main meeting place for those of a Bohemian disposition,

socially unconventional individuals inhabiting the worlds of art and literature. In 1903, Benjamin Ottewell entertained his

Scottish friend, John Michie, then the factor on the Balmoral estate, to dinner

at the Savage Club, followed by a visit to the Alhambra Theatre of Variety. Later, in 1907 on the occasion of the 50th

anniversary dinner of the Club, held at the Hotel Cecil, John Michie was again

Ottewell’s guest. One wonders what

Michie, a Presbyterian Scot from the Highlands, made of these metropolitan

experiences. The Savage Club members

were also involved in charitable work and in June 1907, they mounted an

entertainment, the proceeds to be in favour of the Lord Mayor’s Crippled

Children’s Fund. “The Club’s most

eminent artists including BJ Ottewell contributed sketches and pen and ink

drawings with the result that an illustrated programme unique in its

combination of varied styles and subjects was produced to stand as souvenir of

the event and was sold at a moderate price for the benefit of the fund.“ In 1920, the Dundee Courier reported that

“Several members of the Savage Club, an organisation which has for years

attracted leaders in literature, art, science, music, exploration, politics,

and other departments have been spending a most enjoyable and unconventional

holiday in Braemar. Company included Mr

Arthur Pryde well-known musician, Horace Fellowes leader of the Scottish

Orchestra, Mr Joseph Ivimey, Professor at the Guildhall School of Music, Dr

George Pernet, Dr John Ivimey, and Mr BJ Ottewell.” Horace Fellowes was an outstanding violinist

and became Professor of Violin at the Scottish Academy of Music. John Ivimey was an organist and composer who specialized in comic operas. Dr George Pernet was a leading

dermatologist. Even in the 1920s, (BJ

Ottewell was 73 in 1920) he maintained his contacts with an eclectic group of

thinkers. The venue for the holiday,

Braemar, suggests that Ottewell may have been the instigator and organiser.

Partial catalogue

A list has been compiled of the pictures by Benjamin John Ottewell

which have been offered for sale by art dealers in the recent past. To this compilation had been added pictures

held in private hands which have come to the attention of this author and lists

compiled by members of the wider Ottewell family. Although, given his artistic fecundity, the

list is disappointingly brief, currently amounting to 190 works, it does give

some guidance to his movements. The

earliest entry on this list is, “Field workers in landscape”, which is a

watercolour on brown paper and is dated 1879.

Perhaps the medium indicates that Benjamin was then still suffering

penury? Other titles in the period 1879

– 1881, with one exception, have titles which are not place specific, though

they do not suggest a location in the Highlands of Scotland. Rather, they are consistent with the South of

England. The odd man out is “The Wandle

near Mitcham”, now in the possession of Wimbledon Museum, which is precise as

to the location of its genesis.

Female company and children

His book also reveals that Benjamin Ottewell enjoyed female

company. “I first vowed eternal fidelity

at a very early age.” “Since that time,

I have loved much and very often!” His

list of paramours is a long and amusing one.

Katie, Emily, Emily, Emily, Florence, Annie (who exhibited polydactyly),

Moll, Bet, Doll and Kate constituted the first ten ladies of his close

acquaintance. They were followed by the

amusingly-named Dorothy Draggletail, though her nick-name was not explained and

Mary, much younger than him, whom he clearly met in the Highlands of

Scotland. This lady was “not from our

glen but from Banff, possibly Maggieknockater which lies between Kineavie and

Boharm in the Vale of Fiddich”.

Improbable though the names of these places sound, they do exist and are

located near Craigellachie in the Spey Valley, Banffshire. It would not be unfair to describe Ottewell

as a womaniser.

There was at least one other female companion who appears not to

have been mentioned in the autobiography.

Although he never married, family rumour suggests that Benjamin John

Ottewell had a close relationship with a lady by whom he had several

children. At the 1871 Census Hannah

Sophia Holliman was recorded as the daughter of Henry Holliman, a coachman and she

was born in 1863 at Marylebone, London.

At the next census in 1881 Hannah appears to have been working as a

domestic servant for Stephen Belhome, a builder and his wife living in

Wimbledon, which was also the location of the Ottewell family home at the time. At all subsequent censuses she was described

as being married, with a surname of Clifton, and the 1911 Census recorded her

as having had this status for 30 years, implying a year of marriage of 1881. At the censuses of 1891, 1901 and 1911,

Hannah Sophia Clifton was living with the Willis family in Mitcham (or Tooting,

which is adjacent) and from the 1911 Census it is learned that she and Mrs

Elizabeth Willis were cousins. No record

has been found of a marriage between Hannah Sophia Holliman and a male with the

surname Clifton and no husband named Clifton is present in the family home in

any census post-1881. This alleged

marriage looks fictitious and was probably invented to cover up illegitimacy. The surname “Clifton” may have been borrowed

from a family friend. One of the

witnesses of the marriage of William Ottewell and Ann Pope was an “H Clifton”.

An alternative source is the name of the row of houses, Clifton Villas, in

Colliers Wood, where Hannah Holliman once lived.

Between the census dates of 1881 and 1911, six births, now

believed to be extramarital, were detailed.

These offspring were all attributed with the surname Clifton in the

census returns, though birth registrations differ. The first two children were registered with

the surname Holliman, the remaining four taking the name Clifton. On some birth certificates the father is

identified as “Benjamin Clifton, Artist”.

The children and their birth dates were as follows. John Clifton, January 1882; James Frank

Clifton, October 1883; Lucy Miriam Clifton, 28 January 1888; Catherine Louise

Clifton 3 January 1898 (twin); Benjamin Clifton, 3 January 1898 (twin); Thomas

Benjamin Clifton, 14 November 1904. Two

sets of DNA tests suggest that some, probably the youngest four children of

Hannah Sophia Holliman, were fathered by Benjamin John Ottewell. It will be noted that the two boys in this

quartet both took the given name, Benjamin.

Was their mother signifying the identity of their father by this choice?

Although the association between Benjamin Ottewell and Hannah

Sophia Holliman existed for at least seven years, family rumour suggests that

Benjamin had little or nothing to do with the upbringing of her children. How did Hannah survive financially with

apparently little income? Apparently, she

used to call on Benjamin to ask for money but these visits were not welcome. One location where she used to meet Benjamin to

extract finance from him was the Alexandra pub at Wimbledon Broadway. Is it possible that the relationship was not based

solely upon friendship but contained an element of payment for services

rendered? That possibility has been

suggested by one of the descendants of the couple. Commitment to a family would likely have

curtailed Benjamin’s carousing and yarning with friends, principally in London

and his long painting assignments, mainly on Deeside. Perhaps this would have been a step too far

for this hedonist? Further evidence of a

frosty relationship between Benjamin Ottewell and his children has been related

by a relative. About 1920, by which time

Benjamin must have been in comfortable financial circumstances, he offered to

help fund a venture by one of his children to set up an artists’ supply shop,

but the offer was refused.

Braemar and Royal Deeside

In a brief obituary, which appeared in the Aberdeen Press and

Journal, in March 1937, shortly after BJ Ottewell’s death, it was claimed that

he had been a regular visitor to Braemar on Upper Deeside for “over fifty

years” (at least since 1886). One

picture title (The Clunie near Braemar) from 1884 is the earliest definite

Deeside picture executed by Ottewell. Examination

of the titles of his paintings produced in 1885 does not reveal a single

picture which unambiguously originated on Deeside but at least one, Mid gorse

and fern, which might have been inspired by that locality. Others, such as “A bit of Wimbledon Common”

speak clearly of their English affiliations.

In 1886, “Savernake Forest” (in Wiltshire), “Sheep and lambs in

woodland meadow, early springtime”, “Spring/autumn”, “The oak’s brown side”

“Woodland scene with beech trees” sound like descriptions of English settings

and no clear Scottish painting subject has been uncovered. Perhaps works from North of the Border are

still lurking waiting to be unmasked? However,

the titles for the following year, 1887, demonstrate a marked connection with

the Scottish Highlands. “A Highland glen

with a snow-capped peak in the distance”, “A river torrent”, “Scottish rivers”

are the titles so far uncovered for 1887.

It seems that this was the year that he made his first major journey to

the Highlands, though whether his destination was Braemar and its environs is

unclear. A single picture painted in

1888, entitled “Under the greenwood tree”, has been discovered. In 1889 works such as “River landscapes with

trees, “Country path lined by silver birches” and “The birch-encircled pool”

are ambiguous as to location. One

further offering from that year, “Autumn in New Jersey”, suggests a visit to

the United States, but no other evidence for a transatlantic foray is known. No paintings dated 1890 have been discovered

which might indicate Ottewell’s whereabouts but, in the summer and autumn of

1891, Benjamin John Ottewell was an extended visitor to Braemar. The abundant evidence for this long stay on

Deeside is related to the so-called Braemar Rights of Way campaign in which

Ottewell was not just an active participant, but a ringleader.

The Ballochbuie 1916

The Braemar Rights of Way dispute

To understand the cause of the dispute, it is necessary to look

back at the history of the Highlands.

The Aberdeen Journal explained the situation succinctly. “In former days, in times prior to the

penetration of the North by railways and coach roads, the hills had little

value. They could be crossed and

re-crossed without anyone thinking of asking the reason why, or the pedestrian

meeting a keeper or a fence. But

nowadays a heath or a scrubby mountain or a lonely glen has a higher value than

the same amount of arable land had a century ago, or indeed in these days of

agricultural depression has now. It

feeds grouse and deer which bring more money and employment into the country

than sparse sheep or the crofts of scanty oats and with the wealthy sportsmen

have come the sight-seeing tourists and the fashionable idlers who crowd the

Braemar Gathering and other Celto-Cockney functions of the autumn season. Between these two industries in the north,

game and tourists there is a steady feud.

The latter insist on “rights” to which they have often little

claim. The game interest on the other

hand resent interference with what has cost them so dear.” The fashionable revival of Highland culture

in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and the growing popularity

of country sports had thus generated a tension between the conflicting

interests of two classes of wealthy visitors to the Highlands.

In 1890, Alexander Haldane Farquharson was the 23-year old,

recently graduated, recently elevated owner of the Invercauld Estate, extending

to about 100,000 acres, which was partly located between Braemar and the

Balmoral Estate to the east. His father,

Lieutenant Colonel James Ross Farquharson (known colloquially as “Piccadilly

Jim”) had died two years earlier, handing on control of the Invercauld lands to

his inexperienced and impetuous son. He, with a narrow-minded focus on his

proprietorial rights, instructed his factor, RG Foggo to block a footpath,

which ran from Castleton of Braemar (the part of the village on the east bank

of the river Clunie), to the North Deeside road near Braemar Castle and running

near a prominent cliff called the Lion’s Face rock. This picturesque path had been used for many

years by both local people and visitors and it was treated as a public right of

way. Generally in Scotland, there was

and is an informal pact between the public and the big Highland landowners that

reasonable access to mountains, forests and moors is tolerated. AH Farquharson did not recognise a right by

the public to access the Lion’s Face path as they pleased and he asserted that

the sporting rights of his tenant, Sir Algernon Borthwick MP, were being

compromised.

Most local people felt unable to

challenge the authority of this powerful laird, who controlled the lives of

many of them as landlord and/or employer.

The locals stayed largely silent, but not so the wealthy tourist

visitors, including Benjamin Ottewell, who were mostly immune to the influence

of Mr Farquharson. They took the matter,

literally, into their own hands and broke down the fences erected by Foggo’s

men to prevent access. The fences were

re-erected and the defiance repeated, in all about 16 times over a period of

several months. John Michie, head

forester on the adjacent Balmoral estate observed in his dairy on 18 August

1891 as follows. “The Invercauld Factor

R G Foggo having last year erected a deer fence across part of the Braemar

Market Stance, thereby obstructing what is believed to be a right of way between

the Braemar & Ballater road at a point opposite the Lion's face rock and

the upper part of Castleton. The

visitors to Braemar have last week repeatedly broken down a roadway through the

fence & burned the material as often as the Invercauld workmen erected

it.” Michie recorded these events in a

matter-of-fact way, but probably thought the instructions of Mr Farquharson

ill-advised, since even the Balmoral estate allowing reasonable access to its

land. In the circumstances, it was

inevitable that AH Farquharson would resort to the courts for a solution to the

conflict.

The opponents of Mr Farquharson formed a Provisional Committee for

coordinating their efforts to frustrate the Laird of Invercauld. Its members realised that they would need funds

to pursue their defiance and sought donations by means of an advertisement in

The Times. The composition of the

committee was N Fabyan Dawe (a watercolourist and member of the Society for

Psychical Research), Clift House, Braemar; Henry Robinow (director of De Beers

and speculator in South African diamond mines), Deebank, Braemar; BJ Ottewell (watercolourist), Burnside,

Braemar; Alexander Hendry (son of the Braemar postmaster), Post Office, Braemar;

J Head Staples (later a JP in Cookstown, Co Tyrone), Bruachdryne, Braemar; C

Ramsbottom, Fife Arms Hotel, Braemar; H Branson Firth (son of a steel

manufacturer), Thrift House, Sheffield; TS Milln, Chichester Road, Croydon, Vernon

Weathered (watercolourist and son of a Bristol colliery owner), Honorary Secretary

of the Committee, Burnside, Braemar.

James Bryce, the local Liberal MP, first Honorary President of the

Cairngorm Club and Robert Farquharson were amongst the donors to the

protesters’ fighting fund, which was generally well-supported, though many

contributors kept their identities secret.

One of the committee members, Mr Staples and his wife were so well

integrated into the Braemar community that in August 1895, Mrs Staples

organised a treat for the children of the village, which at least some of the

Michie children attended.

Benjamin Ottewell would himself

probably have branded his fellow protesters as “wealthy loafers”. It is also noticeable that three committee members

were watercolourists, which suggests a route by which Ottewell started to

travel to Upper Deeside to paint. Did

his association with other painters, possibly through the Savage Club, alert

him to the potential of the Deeside scenery to satisfy the needs of the

landscape artist? Its attraction to

Benjamin Ottewell was summarised in his own words as follows. “Our Glen.

No railway station within 20 miles.

Sixty miles from mill or mine.

All who go there once go until they die.

Some in June for long days and salmon fishing, others later for blooming

heather and the slaying of grouse and deer.

Others for golden glories of October.”

Alexander Haldane Farquharson

successfully applied for an interim interdict against Mr JH Staples (“the

gentleman who stepped forward with the saw”).

But that only restrained one individual and the acts of destruction were

continued by others. Mr Farquharson then

made a second application for interim interdict, this time naming all the

members of the Provisional Committee and seeking to restrain them from

“interfering with the fence partially surrounding Craig Choinnich (the hill that the path

skirted around) and from entering or trespassing upon that hill, and from

using the path by the quarry to the Lion’s Face and also from entering or

trespassing on the Lion’s Face Drive, better known as the Queen’s Drive.” The plaintiff maintained in his statement to

the court that the land over which the path was routed was private and that no

right of way existed. He also specifically cited BJ Ottewell as a person who

had participated in the destruction of the fence. In the meantime, the residents of Braemar

continued to use the path and Mr Foggo’s response was to station an unfortunate

ghillie at the gap in the fence to demand names of those crossing this

boundary. He was generally ignored.

As a result of the lodging of this

second plea for interim interdict, George Cadenhead, Procurator Fiscal for

Aberdeenshire travelled to Braemar to take witness statements. Subsequently, interdict was granted but

contacts between the two opposing sides were established and in 1893 a

compromise was reached. The interdicts

were lifted, and the path opened to public use, except between 20 September and

30 November, the busiest part of the shooting season.

Victor Fraenkl

One consequence of Benjamin Ottewell’s close involvement with the

Lion’s Face rights of way campaign was that he met and became friends with a

German immigrant, Victor Fraenkl, a partner in a Dundee firm of linen and jute

exporters, Jaffe Brothers. Fraenkl was

also the German Consul and a prominent member of the Jewish community in Dundee. Victor Fraenkl was a visitor to Braemar in

the early 1890s and he became a supporter of the protest campaign, subscribing

to its fund in his own name rather than using a pseudonym, such as

“Wellwisher”, “Friend”, “Visitor”, “Anon.”, “Freedom”, “Corstorphine” or

“Justice”. Mr Fraenkl also bought some,

possibly many, of Benjamin Ottewell’s watercolours. John Michie mentions that

on several occasions, Benjamin Ottewell was a guest of Victor Fraenkl at his

grand house at Tay Park, Broughty Ferry, an upmarket settlement four miles east

of Dundee. On Sunday 30 May 1897

Ottewell stayed overnight at Tay Park on his journey south from Deeside to

Wimbledon and at early New Year 1904, he was a guest of Mr Fraenkl for several

days while on his way north to Aberdeenshire. Ottewell returned south at the

beginning of February and again called in at Broughty Ferry. John

Michie also visited Fraenkl at Tay Park to take tea at the end of March 1909, at

a time when Ottewell was once more a guest of Victor Fraenkl. Their host had recently undergone an operation

on his stomach and, sadly, Fraenkl did not survive for long, dying in mid-June

of that year. In the October after his

death, Victor Fraenkl’s picture collection was auctioned and raised the sum of

£1200 (about £140,000 in 2018 money).

Included in the sale was “Meadow and Mountainside” by Benjamin Ottewell,

which had been exhibited at the Royal Institute of Painters in

Watercolour. It fetched £30 (about

£3,500 in 2018 money). It is not

known how many Ottewell paintings Fraenkl owned but, over the next 20 years,

other Ottewell works appeared for sale sporadically in the Dundee area. For example at an auction held by Robert

Scott and Sons, Fine Art Dealers, 19 and 21 Albert Square, Dundee in 1922, in

the same town by the Dundee Auction Rooms a year later and, in 1924, Robert

Curr and Dewar, auctioneers, offered “Wooded Landscape” by BJ Ottewell. Further Ottewell works were put up for sale

at the Mansion House, Taypark, in 1928, then in the ownership of a Mrs Danby

and at “Bayfield”, West Ferry,

Dundee a year later, “Autumn” by BJ Ottewell was one of the works on offer. It seems likely that this cluster of Ottewell

paintings originally arrived in Dundee due to their purchase by Victor Fraenkl.

Growing status as an artist

Benjamin Ottewell, by the early 1890s,

was becoming more established within the arts community and he continued to

display his work. In Braemar, in

September 1891, an exhibition was mounted by artists in the visitor community,

all of whom had previously been successful in having pictures accepted by the

Royal Academy. In Ottewell’s display, “The Callater Burn in spate” and “Evergreen Pine”

attracted much attention. October 1892

saw Ottewell exhibiting at the New Gallery with “Where sleeps till June

December’s Snow”, a title which captures a marked characteristic if the

Cairngorms before the turn of the 19th century. 1892 also saw Ottewell exhibiting at the

Royal Academy again with “Across the heath”, possibly not a Highland scene. At the end of 1893, the Aberdeen Journal

advised its readers to visit a display of BJ Ottewell’s work in the shop window

of Gifford and Son, carvers and gilders, printsellers and artists’ colourmen at

265 Union Street, Aberdeen’s main thoroughfare.

The newspaper described his works as follows. “Lovers of Highland scenery have an

opportunity of inspecting in Messers Gifford and Son’s window at present two

admirable water-colours by Mr BJ Ottewell who has for the two past seasons

found employment for his pencil in the Braemar district. The first and more elaborate picture is a

view from the Lion’s Face road looking northward across the tops of the hills

towards Ben Avon the peaks of which fill up the background. In the intervening forest and hills are some

fine effects of light and shade and the whole subject, a somewhat difficult one,

has been admirably treated. The other

picture is a study of fir trees &c in the forest on the skirts of Craig

Choinnich, a subject which Mr Ottewell’s style of water-colour drawing shows to

much advantage.” The descriptions of the

two works, whose titles were not given, could have been pictures he had already

displayed at Braemar (“Evergreen Pine”) and at the New Gallery (“Where sleeps

till June December’s Snow”). In any

case, Benjamin Ottewell had clearly been enjoying the hard-won freedom to use

the path to the Lion’s Face across Mr Farquharson’s land. Both were painted from that vantage point, as

the Aberdeen Journal report makes clear.

Though much of BJ Ottewell’s work in

the early 1890s dealt with subjects from around Braemar in the Scottish

Highlands, not all his efforts were directed to depicting scenes found north of

the border. One of his 1893 pictures was

titled “The Littleworth Road, Burnham Beeches”, which is a location in

Buckinghamshire. Another, from 1895,

took the name “The Swilley pond Farnham”, which is in Surrey.

Initial meeting with Queen Victoria

It has been pointed out above that one of Benjamin John Ottewell’s

principal marks of fame was his sale of many works to Queen Victoria. In his biography he deliberately tries to

obscure her identity and he describes their first contact, which he

characterised as one of his many pieces of good luck, as follows. “I made the acquaintance of a great lady

through lack of agility – inability to get out of sight quick enough round the

corner of a road and during the following six years sold upwards of 130

drawings to her besides many others to members of her family.” It seems likely that Ottewell had been

painting on the Balmoral Estate, perhaps without permission and possibly on the

part of that estate which abuts the Farquharson land at Craig Choinnich. The Monarch was no mean artist herself, was a

keen collector of works of art, had a deep attachment to the countryside around

Balmoral and so would be almost certain to take an interest in the efforts of a

fellow artist painting on Upper Deeside.

Although by the 1890s Queen Victoria’s mobility was limited, she still

drove out almost every day, usually in her “pony chair” and the estate road

westwards, emerging by the Lion’s Face and exiting to Glen Clunie near Braemar,

via the Queen’s Drive, was one of her favourites. Ottewell’s words, “During the following six

years”, almost certainly dates the meeting to the year 1894 or 1895. The Queen died on 22 January 1901, so the

year 1901 should be discounted, which results in a count-back of six years from

1900. It is to be wondered if the

meeting of Monarch and artist was coincidental, or if Ottewell engineered his

piece of good luck. Other evidence points

to the year 1894 as being the correct alternative. One of Ottewell’s paintings, dated 1894, had

the title, “Mrs Mitchie’s cottage,

Balmoral”. This was the home of John

Michie and his wife Helen, which was called “Danzig Shiel”. It was built about 1880 after Michie was

appointed as Head Forester and is located at the foot of the Ballochbuie Forest

about five miles west of Balmoral Castle and about half-way to Braemar. Queen Victoria was a frequent visitor to

Danzig Shiel, where she often took tea with the Michies. Danzig Shiel also contained two rooms for the

Monarch’s exclusive use, which Helen Michie was employed to clean. The failure by Ottewell to spell “Michie”

correctly suggests that at the time he may only have recently made the

acquaintance of Helen Michie and may not then have met John Michie, otherwise

the cottage’s attribution would likely have been to him. Other evidence pointing to 1894 as the date

of the meeting is contained in the Court Circular of 8 November 1894. “Mr B Ottewell had the honour of submitting

some of his water-colour sketches of views on Deeside for Her Majesty’s

inspection.” This presentation is likely

to have followed shortly after the first meeting with the Queen, which could

not have therefor been later than 8 November 1894. That year the Queen’s second visit to

Balmoral extended from the end of August to the middle of November.

The Danzig Shiel 1896

The hard winter of 1894 - 1895

The Linn of Dee is a steep defile in a narrow part of the upper

Dee, ten miles west of Braemar and a magnet for painters and tourists

alike. It is the striking off point for

long distance paths to Speyside, via the Lairig Ghru, and to Blair Atholl through

Glen Tilt. The Linn of Dee displays

spectacular scenery and it was almost inevitable that the Linn would be

frequented by Benjamin John Ottewell while lodging at Braemar. The year of Ottewell’s first visit to the

Linn of Dee is difficult to state with certainty, but could have been 1887, the

year after his first acceptance by the Royal Academy. He was lodging with a poor, widowed “wifie”

at £1 per week. She had been left with

eight children and an annuity of £10pa.

To make some additional income she “Let her spare rooms to tourists and

mountaineers and also supplied teas and other small refreshments”. Besides her humble friends she also became

acquainted with “the greatest lady in the land” (Queen Victoria) and the

first meeting was when she was very young.

Never a year passed without a call from the “great one”. The wifie was rather fat and when Queen

Victoria enquired after her health she would respond with “I’m as fit to row as

to rin.”

One day Ottewell, while residing at the Linn suddenly realised

that, as he had broken into his last sovereign, he was about to run out of

money. But then he was saved by another

piece of the good luck, which he claimed had visited him throughout his life. An angler fishing unsuccessfully nearby in

the Dee caught his attention and after some conversation bought £60 (about

£7,400 in 2018 money) worth of his pictures, ten times the annuity income of

Ottewell’s landlady.

An entry in Queen Victoria’s Journal for 4 June 1895 confirms that

Benjamin Ottewell also lodged at the Linn of Dee in the winter of 1894 –

1895. “Took tea at the Dantzig Shiel with Beatrice &

Louisa A. Saw there some beautiful sketches by an artist of the name of

Ottewell, who has spent several months in Braemar,

painting, having been snowed-up for some weeks, in the winter, at the Linn of

Dee.” That winter is recognised by

climatologists as having been particularly severe. It came at the end of a decade of very bad

winters throughout Great Britain and is viewed by some meteorologists as the

end of the so-called “Little Ice Age”.

Ottewell wrote about his experiences as follows. “The winter of 1894 – 1895 was one of

the most severe of our time and lasted over 15 weeks from 27 Dec to the middle

of April. Snow fell fine as flour for

weeks. Frost bound the river and snow

covered it from sight. The cold was

intense. Saw 13 hinds and stags lying

dead within 100 yds of each other.” A

hedgehog even took up residence in the kitchen of the cottage where Ottewell

was lodging, in order to escape the cold.

First meeting with John Michie

The first mention in John Michie’s diaries of him meeting Benjamin

Ottewell was on 4 April 1895. “At Bridge

of Dee we met Mr Ottewell the Artist who I caused to apply for Colonel Bigge's

authority ere I would consent to take him into my house while he sketched in

Ballochbuie forest.” The “Bridge of Dee”

is located near the entrance to the Invercauld Estate, about seven miles east

of Balmoral Castle and was built in 1859 to divert the road between Braemar and

Ballater from the south bank of the Dee to the north bank in order to improve

privacy and security for the Royal family while at Balmoral. The exact meaning of this diary entry is

unclear but the implication could be that John Michie was aware of Ottewell’s

residency in the district but was unsure of his status with the Royal family,

hence the reference of the matter to Colonel Bigge, who was the Queen’s private

secretary at the time. The reference to

“take him into my house” almost certainly means that it was being proposed (by

Her Majesty?) that Ottewell should become a lodger with the Michies while he

painted in the Ballochbuie. This forest

was and is one of the most picturesque parts of Deeside and contains remnants

of the ancient Caledonian Forest with many mature Scots Pines.

A friendship develops

It is clear from further entries in John Michie’s diaries that

Benjamin Ottewell did lodge with the Michies, perhaps for as long as two months

in April – June 1895 and quickly became a friend of the Michie family. The children of John and Helen Michie, seven

in total, would have ranged in age from Alexandrina (3) to Annie (16) at the

time. Ottewell was known to them as

“Uncle Bones”, which sounds like a child’s corruption of “Uncle Ben”, the

sobriquet Ottewell had worn since an early age.

The first diary reference to Ottewell had been on 4 April. Others quickly followed. Monday 8 April. “Had a stroll through the woods with Mr

Ottewell and spent evening in reading yesterday (ie Sunday, probably in

preference to attending church at Crathie about 6 miles distant).” Monday 22 April. “Yesterday walked to Craig Darign with Mr

Ottewell the Artist instead of going to church.” Tuesday 23 April. “Mr Ottewell still paints scenes in the

Ballochbuie forest. Today he has been

working on a picture of the Fiendallacher at the high bridge on the crosswalk

above the junction of that stream with Garrawalt.” Friday 26 April. “ … in the evening drove down to Balmoral and

went to a concert in the Iron Ballroom. … Mr Ottewell the Artist went down

along with me.” Wednesday 15 May. “ … in the evening drove to Braemar with Mr

Ottewell, thence to the Linn of Dee.”

Monday 20 May. “Remained at home

yesterday being tired but walked by the Brig o'Dee in the afternoon with Mr B J

Ottewell the Artist who is still staying with us & whose company I relish

very much.” Tuesday 21 May. “At the Invercauld Arms (Braemar, that

evening) we Mr Ottewell & I played a game at billiards, or rather he gave

me a lesson in the game.” Saturday 1

June. “By arrangement with Sir Fleetwood

Edwards (Keeper of the Privy Purse) took nine water colour drawings by B

J Ottewell down to the Castle for the Queen's inspection. Left them with Sir F and proceeded to Birkhall

… .”

These exchanges illustrate just how personable Benjamin Ottewell

was. He appears to have been thrust upon

the Michies with little foreknowledge but was able to charm the family to such

an extent that a stay of about two months did not seem to prove burdensome to

them. John Michie would later describe

Ottewell as an “artist and humorist”.

Ottewell went south soon after leaving the Michies but he returned in

early July 1895 “to spend a night with us on Mrs M's invitation, on his way to

Braemar where he means to reside during the remainder of the summer.”

A developing relationship with the Royal family

Benjamin Ottewell also appears to have charmed Queen Victoria and

several of her daughters and grand-daughters.

During the Monarch’s second visit of 1895 to Balmoral, which lasted from

the end of August to the middle of November, there were significant contacts

between the Royal party and the artist. On 8 October, John Michie recorded that he

was interrupted in his work by a message that the Queen was coming to tea at

Danzig Shiel. “This put me off

& after she, the Princesses Beatrice & Christian (Helena, Queen

Victoria’s third daughter and fifth child, who married Prince Christian

of Schleswig-Holstein in 1866 ), Prince & Princess Henry of Prussia (Princess

Henry was a granddaughter of Queen Victoria whose mother was Princess Alice,

the Monarch’s third child and second daughter) & Princess Victoria of

Schleswig-Holstein (Princess Helena’s daughter) left drove Mr Ottewell

to Braemar to get one of the pictures he had sold to a Mrs Osborne to show the

Queen &c tomorrow, he having been commanded by the Queen to go down &

the Princess Christian asked me to drive him, with his stock of paintings.” Ottewell had clearly stimulated great

enthusiasm for his work with Balmoral’s Royal residents. John Michie also reported in his diaries that

in May 1897 he took BJ Ottewell with him to Balmoral Castle to see Princess

Christian, though it is not clear what was the purpose of this interview.

Following his initial encounter with Queen Victoria on the

Balmoral Estate, it seems likely that various members of the Royal family recommended

him to paint some scenes near other Royal residences. Resulting works included “Windsor Castle from

the Park”, painted in 1895 and King’s Quay, Osborne, 1896, the latter produced at

the suggestion of Princess Henry (Beatrice).

It appears that Ottewell was, on at least one occasion, provided with

accommodation at Windsor, in The Cottage, Cumberland Lodge, located in Windsor

Park. Queen Victoria recorded in her

Journals on 28 May 1896, “After 5

drove with her & Marie L. to below the Falls of the Garravalt, where we had tea & then drove by

the Old Bridge to the Dantzig, where we stopped to look at some lovely sketches by Mr Ottewell, which the Michies brought out for us to look at.”

It was reported in March 1897 that, “The Queen’s visit to the

sunny South (of France) is causing a good deal of excitement in that

part of the world and Her Majesty has shown her appreciation of the lovely

scenery by entrusting Mr BJ Ottewell with a commission to paint her several

pictures of the landscapes she loves so well.

He is accompanied by an amateur painter of great efficiency, Mr Pitt

Taylor and both are busily occupied in sketching.” Pitt-Taylor had also been in Braemar in

October 1896. Benjamin Ottewell refers

to this journey to the South of France in his autobiography. “Fifteen years ago, my great Lady Patron

commissioned me to make a series of sketches in the South of France.” Ottewell mentions places visited as including

Faicon near Nice, the valley of the Vesubie north of Nice and Pera Cava near

the Italian border. Three paintings

dated 1897 by Ottewell have the titles “A view of a castle in a Highland

landscape”, “Grey day at St Pons” (St Pons is a village in the Alps about 80

miles north-west of Nice) and “The Gorge of St Andre, the Alps in the distance”

(located adjacent to St Pons). The last

two works listed for 1897 must surely have been produced on the assignment at

Queen Victoria’s command. It was also in this period that Benjamin Ottewell was

engaged by Her Majesty to teach painting to Princess Henry (ie her youngest

daughter Beatrice). Queen Victoria

recorded in her Journal for 24 April 1897, written at the Hotel Regina, Cimiez,

“Sat with Beatrice whilst she painted with Mr Ottewell.” The

Aberdeen Press and Journal’s brief obituary of Benjamin Ottewell, published in

March 1937, noted that he gave painting lessons to “several of the royal

princesses”.

A descendant of Benjamin Ottewell reported, “Several years ago I

was told by an East Anglian art dealer that he sold an Ottewell painting of

Windsor castle dated 1902. On the

painting was an inscription saying that the painting had been a present to the

Queen of Spain on the event of her marriage.

On the back of the painting was a sketch of Queen Victoria collecting

blackberries. Without my prompting he

said that Ottewell had taught Queen Victoria’s grandchildren to paint.” Perhaps most intriguing is the existence of

the sketch on the back of the main picture.

Such an informal drawing of the Monarch would surely only have been

countenanced by her if Benjamin Ottewell was a trusted and familiar associate? Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg (1887 – 1969)

was the only daughter of Princess Beatrice and her husband Prince Henry of

Battenberg. She married King Alfonso

XIII of Spain in 1906.

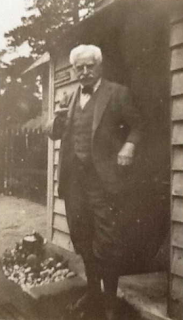

Benjamin John Ottewell

Queen Victoria's and Prince Albert’s

etchings

Queen Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on

10 February 1840. Over the next decade

she bore seven children. Prince Albert

died on 14 December 1861, allegedly of typhoid fever, though doubt has recently

been thrown on the accuracy of that diagnosis.

Queen Victoria was a keen artist and between 1840 and 1845, Her Majesty

frequently referred in her Journal to the Royal couple creating etchings of a

variety of subjects, including portraits of their dogs and children. On occasions, she was helped in this work by

Edwin Landseer, famous for his emotional animal portraiture. Etching involves covering a metal plate,

typically copper, with a wax layer and then incising the metal through the wax

layer to create a picture. Acid is then

used to eat into the metal where it is exposed and the acid and wax

subsequently cleaned away. The metal

surface is then inked and the surface wiped leaving ink only in the depressions. A sheet of paper is then applied to the metal

and the metal plate and paper run through a printing machine to impress a

mirror image on the paper. The same

metal sheet can be used repeatedly to produce many prints.

Altogether the Queen produced 62 copper plates and the Prince a

further 25. Very few and incomplete sets

of prints from these plates still exist, as they were only ever intended to be the

products of a Royal hobby. Prints were

produced for Victoria and Albert by a local printer in Windsor, John Brown, but

one of his employees by the name of Middleton, produced extra copies. He sold a collection of 63 different prints to

Jasper Thomsett Judge who tried to exploit this breach of Royal copyright by

mounting a public exhibition for which catalogues were produced. Prince Albert successfully used the courts to

prevent the publication and exhibition of prints of the engravings.

A second theft of Royal etchings?

In his autobiography, Benjamin John Ottewell relates a yarn

originating with an acquaintance whom he calls “Barabbas”, no doubt because of

his “tendency to dishonesty”. (The

original, Biblical Barabbas was a prisoner at the same time as Jesus of

Nazareth and was due to be executed, but was freed by Pontius Pilate.) The “Barabbas” tale involved the acquisition

by him of prints produced “a long time ago” by “the great lady at the Castle”

and “Hubbie”. In this story “Barabbas”

alleges that a theft of prints from the castle was detected and, after an

investigation, a footman dismissed without a pension. Subsequently the former employee fell on hard

times, partly through drink and illness.

This man was responsible for the removal of the prints because he sent

his wife to “Barabbas” to tell him the story and to ask him to visit their home

to view the prints. When shown some of

the pictures, “Barabbas” immediately recognised their authorship, as they had

been signed by both etcher and printer. Ottewell’s

mendacious friend then acquired all the prints in the possession of the former footman

and his wife for two guineas plus “an extra quid”. The prints were hot property and not easy to

place and “Barabbas” did nothing for a long time. He claimed he knew the “private secretary” at

the Castle and wrote to him letting the Royal employee know that the etchings

had “come into my possession in a very extraordinary way” and that he would

return them. The private secretary

replied, “as I knew he would”, saying that the affair had blown over and “for

God’s sake let it remain so”. “Barabbas”

was told he should dispose of the etchings quietly. He claimed to have then found “an American”

who paid him £100 (about £12,000 in 2018 money) for the lot, except

that, “Oh I kept most of the best for myself.”

There is little doubt that the “Barabbas” story relates to the

print-making activities of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Windsor Castle

in the 1840s. It is a fantastical tale

and it would be easy to dismiss it as an invention, which evolved from the true

events in Windsor, elaborated and transmogrified by a fertile mind under the

influence of substantial quantities of alcohol, by frequent repetition and

elaboration. But, if it does contain a

basis of truth, is it possible that it refers to a second, presently unrecognised,

theft of Royal property from the Castle?

It certainly differs from the established crime in several fundamental

ways. The theft was from inside the

castle by a Royal servant, not from the town by an employee of a printer, a

senior courtier chose to cover up the theft, rather than advise legal action

and the prints were acquired illegally by a dodgy individual who sold them on

to an American. Without any independent

evidence to support the anecdote, it is likely to be discarded as fanciful but,

at the same time, it is not so outrageous that it can presently be judged to be

completely implausible.

Ottewell’s integration into the life of Upper Deeside

Being very personable and sociable, and residing in Braemar for

weeks or months at a time, it was inevitable that Benjamin Ottewell would

become intertwined in the social life of the village. He was already regarded as a champion of local

residents’ interests through his involvement in the Lion’s Face path campaign

of the early 1990s. At the annual

meeting of the Young Men’s Catholic Association in Braemar, held in November

1894, Benjamin Ottewell was thanked for “a very handsome drop-scene which he

lately presented to the Society for scenic purposes”. His musical abilities were also in demand and

in September 1895, the Dundee Courier reported as follows. “Last

Monday evening another of the series of concerts which have proved so

successful at Braemar took place in the Victoria Hall. Mr BJ Ottewell again conducted and the choir,

which is one of the largest yet brought together, acquitted themselves most

creditably."

Benjamin John Ottewell continued to frequent Upper Deeside with

extended stays, even after the death of Queen Victoria. He maintained his friendship with John Michie

and often lodged overnight, or occasionally for longer periods, at both Danzig

Shiel and at Bhaile na Choile, John Michie’s house during much of his tenure as

Balmoral factor. Being well-connected in

the Braemar community of both locals and visitors, Ottewell would, from time to

time, turn up at the Michies’ home accompanied by prominent visitors. One such contact, who accompanied Ottewell in

May 1897 was Edward Cunningham-Craig, a prominent Scottish geologist who

carried out significant mapping work for HM Geological Survey between 1896 and

1907. In May 1911, Ottewell visited the

Michies in the company of two prominent friends, Mr Woods, a London stockbroker

and Mr Shirran, the bank manager at Braemar.

The year 1895 brought tragedy for the Brown family of Balmoral.

Albert Brown, the doctor son of William Brown, John Brown’s brother, died

suddenly of peritonitis, at the age of 26. He had only completed his medical training two

and a half years previously and was living in Camden, London. This was devastating,

not only for William Brown and his wife, but also for Queen Victoria, whose

affection for John Brown to a significant degree extended to the whole Brown

family. Mrs Helen Michie immediately

visited Mrs Brown “to pay her sympathies”.

The funeral took place from Bhaile na Choile, which was built for John

Brown by Queen Victoria and was occupied at the time of Albert’s death by his brother

William. Benjamin Ottewell arrived at

the Michies’ house just before the funeral to stay for a fortnight. John Michie wrote in his diary, “Rain this

morning with cold wind from the noreast.

Drove Mr O (Ottewell) down & took my kilt suit with me for

the funeral of Albert Brown as HM insists on wearing it even on these solemn

occasions. The funeral service took

place at Baille-na-Choille about 3 pm, the Queen being present. The whole obsequies were conducted in

continuous rain & wind which continued till dark. Ottewell & I reached home about 5.30

thoroughly wet.” Thus, Benjamin Ottewell

was so well accepted at Balmoral that he felt it appropriate to attend Albert

Brown’s funeral and John Michie thought it in order to take him there.

Another reflection of the frequency of Benjamin Ottewell’s visits

to Braemar was his mastery of the Doric, the Aberdeenshire dialect of the

English language. He was even familiar

with the book “Johnny Gibb of Gushet Neuk”, which was written by journalist

William Alexander using the local argot.

This work is recognised as one of the finest descriptions of rural life

in Aberdeenshire in the mid-19th century.

Queen Victoria died at Windsor Castle on 22 January 1901. She had been on the throne for 64 years and

there was a great outpouring of national grief at her passing. Many actions were subsequently taken on a

local level to raise memorials to a much-loved monarch, not the least on the

Deeside estates of the late Queen.

Benjamin Ottewell was so much part of the community and had some

familiarity with the Monarch, that he was included in the estate meeting to

discuss a memorial. John Michie recorded

in his diary on Saturday 20 April 1901 as follows. “Attended a meeting of Tenants & Servants

convened to consider what form a Memorial for the late Queen Victoria will take

to be subscribed for by them. Mrs M,

myself & Alex. with Mr Ottewell drove down, lunched with the Forbes (the

Balmoral factor) at Craig-gowan and proceeded to Abergeldie Castle where

the meet was held.”

Golf on Upper Deeside

A golf course was created on the